Literacy underwrites world’s most spied-on state

Poetry’s layers of meaning exposed people’s deepest thoughts.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

Poetry’s layers of meaning exposed people’s deepest thoughts.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

Before progressive causes became the realm of the professional middle class, writers and artists looked to socialism for ideological comfort.

Sadly, no society has lived up to the utopian hopes of equality and collective wealth that has filled thousands of books and inspired countless works of art.

The most ambitious example was born in the ruins of Berlin in 1945 when an exiled member of the German Communist Party (KPD) returned from 12 years in Moscow.

Johannes Becher, a Bavarian-born poet, was determined he and his fellow Germans would reject the philistine barbarity of the Nazis and restore one of Europe’s great cultural traditions.

Hitler’s regime had mocked artists, hounded writers, and burnt their books and paintings. Becher believed any effort to rebuild the country would put culture back at the centre stage. Though Germany’s defeat was its greatest and most shameful, he was convinced the land of Goethe and Schiller could again become a new and better place.

“It lives, lives among us all,” he wrote of Germany’s intellectual past. “A different, secret Reich.” A Germany where Weimar was the centre of 18th-century classicism, Wittenberg witnessed Luther posting his theses that heralded the Reformation, and Leipzig was the home to first daily newspaper.

The now-closed Karl Marx bookshop in Berlin was a feature of the GDR.

German was the language of Hegel, Marx, and Engels, who laid the foundations of socialist philosophy. The Communist Manifesto promised no-one would be forced into a life of labour, and the abolition of capitalism would offer the kind of freedom that “each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes”.

No social division

Becher took that to mean the new social order would have no division between workers and intellectuals. Instead, there would be workers who wrote and writers who worked. He gave a name to this: Literaturgesellschaft (literature society).

Creative writing would not merely reflect social conditions but shape them. As a poet, Becher believed the new Germany could fulfil the dynamics of Hegelian-Marxian dialectics: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. He outlined his thinking in an essay on the philosophy of the sonnet, with its 14 lines and rhythmic structure.

Becher was no dreamer. He formed the Kulturbund, a group dedicated to the renewal of German culture and with highly placed political clout. He set up two literary publications, a publishing house (Aufbau) and commissioned an uplifting anthem from composers Eisler and Schoenberg.

Exiled Germans were persuaded to return, among them Bertolt Brecht, whose Berliner Ensemble became admired around the world. Its opera house was one of the few places in Berlin that was lit up after dark during the post-war period of scarce electricity.

The writer Hans Fallada, whose bestselling books were suppressed by the Nazis, survived the war but was in ill health. His most famous book, Alone in Berlin, was published in 1947, the same year as his death. Becher had given him the Gestapo file on a couple who distributed anti-Nazi leaflets until they were arrested and executed in 1943.

Philip Oltermann.

Cultural history

Becher’s story is recounted by Philip Oltermann in The Stasi Poetry Circle, a cultural history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which was dissolved in 1989. Becher was appointed minister of culture in 1954 and died of cancer four years later.

His legacy was a country with a degree of literacy that exceeded the wildest dreams of the workers’ education movement in the West. Factories and offices had to have libraries of up to 1000 books. Its publishing industry, at six to nine books a head, published every year, put it at the top of world charts. (Left-wing bookshops in the West were stacked with cheap classics in English from Seven Seas Books in the 1960s and 1970s.)

Every branch of industry had writers’ circles, where authors such as Christa Wolf displayed their talents. Her breakthrough novel Divided Heaven (1963) was written while seconded to a train wagon manufacturer.

If Becher was the idealistic angel of literacy, its devil was Friedrich Wolf (no relation to Christa), who was an established poet long before the GDR was established. Like Becher, he spent some of his exile in Moscow.

On his return to Germany, Wolf helped established the DEFA film studio, set up a branch of PEN international, published an art magazine called Kunst und Volk, and chaired an association of theatres.

The Chekists’ poetry circle was based in the Stasi headquarters in Berlin.

Class struggle

Wolf insisted writers should not get a free ride as employees of the state and instead be at the sharp end of the ideological class struggle. One of his four sons, Markus, became a leading figure in the notorious Stasi, or secret police, which plays a special role in Oltermann’s narrative.

Another son, Konrad, was an influential filmmaker, who adapted Christa Wolf’s Divided Heaven (1964) among many of the GDR’s better movies.

Oltermann describes the “cadre file” that tracked the lives of every citizen from primary school. Compiling the files became the primary occupation of the state security agency, making the GDR an early model for the surveillance society.

These files, which are now accessible by all former GDR citizens, provided detail for Oltermann’s research into activities of poetry circles within the Stasi itself. No agent was too low or too high for regular sessions on studying poetic structure, metaphor, and other techniques of literary criticism.

The author delves into five examples, some of whom he was able to interview after unification.

Poet Ewe Berger, who led the Stasi’s Berlin circle, published two autobiographies, one under the GDR and in 2005. His Stasi file, as an informer and subject, comprised 2214 sheets in six volumes.

‘Inner selves’

As the bureaucracy’s top literary figure, Berger viewed manuscripts before publication, giving him unparalleled access to the Stasi poets’ revelations about their ‘inner selves’. They proudly labelled themselves as Chekists, named after the Bolsheviks’ original secret service. For Berger, the best Chekist spies had “cool heads, hot hearts, and clean hands”.

Annegret Gollin’s background was completely different. Her poetry circle was a target for Stasi surveillance. She was arrested for her rebellious behaviour and none of her poetry was published in the GDR before her freedom was purchased by West Germany in 1982 as one of nearly 1500 political prisoners. She was among 150 formal proceedings taken against writers from 1970.

Other subversive writers tested the limits of the Stasi to detect messages hidden in cryptic verses or prose. The prolific Alexander Ruika was physically intimidated into becoming an informer, while Gerd Knauer’s apocalyptic epics defied interpretation. A diary of his Stasi years reveals how the service collapsed overnight when the Berlin Wall fell in November 9, 1989.

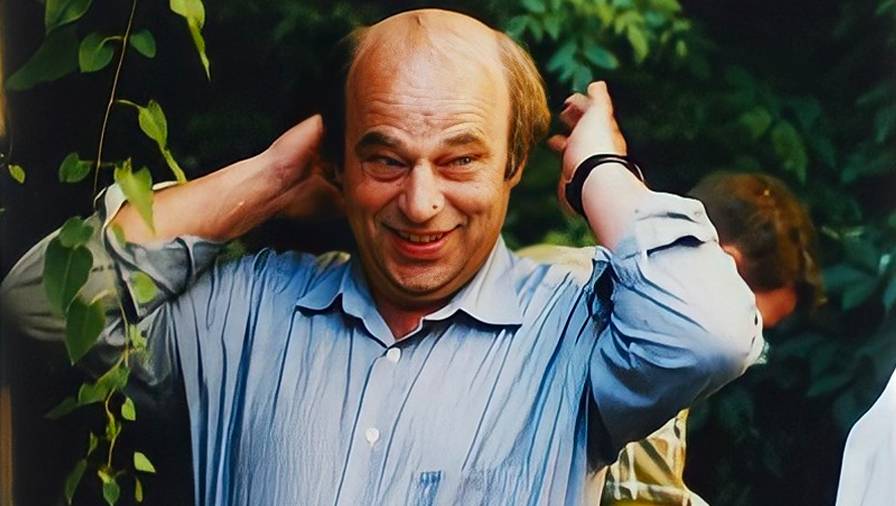

Gert Neumann.

In contrast, Gert Neumann (above), a locksmith, was a master of everyday realism written in cryptic language. He said the dictatorship of “black words” had “murdered” poetry. This did not impress the censors. His first two novels were eventually published in the West to much acclaim.

Oltermann observes the irony that ordinary reality was cause for suspicion. “In many ways it was literature as the founders of the socialist GDR had envisaged it: art made by the working people, for working people, among working people.” It’s a suitable epitaph for socialism’s failure to fulfil even its most basic cultural purpose.

The Stasi Poetry Circle: The creative writing class that tried to win the Cold War, by Philip Oltermann (Faber).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content.