Five questions with the Wolf of Wall Street

'I don't feel guilty' — Wolf of Wall Street, as he prepares to hit NZ

'I don't feel guilty' — Wolf of Wall Street, as he prepares to hit NZ

"Wolf of Wall Street" Jordan Belfort (51) will hit NZ June 26 for a motivational talk-cum-sales seminar.

For the most lucrative part of his career, as he made up to $US50 million a year, the key to his sales success was lying.

After the 1987 crash saw him lose his first job on Wall Street, the Bronx-raised Belfort fell into the business of selling penny stocks; the often near-worthless "pink sheet" shares of companies outside the regulated Nasdaq and NYSE.

At first, he cold-called the (usually blue collar) people who answered classified ads. Small sums were involved, but he took a 50% commission on the pink sheet trades, compared to the 1% he had earned on Wall Street.

Then, with his own brokerage, Stratton Oakmont, he had a an epiphany: why not sell penny stocks to the richest 1% of Americans?

From 1989 to 1996, the brokerage boomed.

Stratton Oakmont's army of brokers in suburban Long Island, New York — which grew to around 1000 — would jump on the phones to push a company's shares on buyers. Their collective efforts would push up the stock. Through nominees or "rat holes" as he called them in his autobiography The Wolf of Wall Street, Belfort secretly held shares in the companies Stratton was boosting. Once the price was pumped up, the nominees would dump their shares and (minus a commission) pass the profit to Belfort.

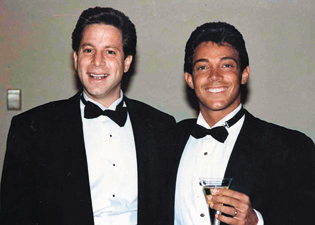

Belfort (right) with his childhood friend Danny Porush in 1994. The pair worked together at Stratton Oakmont, and Porush took over the firm after Belfort departed in 1996 under as part of a settlement with the SEC. After agreeing to cooperate with an FBI investigation, Belfort secretly recorded Porush — and without slipping a warning note across the table, as depicted in the movie (where a composite character based on Porush is played by Jonah Hill). The pair fell out.

As Belfort readily concedes in his book, the way Stratton used nominees violated securities laws. After years of cat-and-mouse, he eventually cooperated with an FBI investigation. He was indicted in 1999, and in 2003 was sentenced to four years' prison for defrauding investors of around $US200 million.

He was also ordered to pay restitution of $US110 million to victims — around $US12 million of which has been paid back so far, mostly from the sale of properties seized by the US government.

The Wolf of Wall Street was made into a movie of the same name, directed by Martin Scorsese. It opened in December and went on to gross $US389 million, and earn five Oscar nominations. The flick pushed Belfort into the mainstream of popular culture, which he's capitalising on with a new tour.

Belfort's 170-foot superyacht, Nadine, which sank during a storm off the east coast of Sardinia, while crossing from Porto Cervo to Capri in 1997. The broker — off his head, as usual — egged on his captain to sail despite the high seas.

Belfort never tried to keep his head down. Friday afternoon celebrations of Stratton's success included the likes of dwarf-throwing and strippers in the office. Prodigious numbers of prostitutes were charged to company credit cards. And Belfort consumed large and ever-increasing amount of drugs, his personal favourites being Quaaludes (which often reduced him to a drooling stupor) and cocaine (to wake him up — although given he talks at about 300 words per minute sober, the mind boggles what he was like on coke).

Scorsese's movie largely ignores the financial mechanics of Belfort's offending, and often takes a tone of comic exuberance as it concentrates on his Belfort's Bacchanalian lifestyle. The reality was a bit more grim. he hit rock bottom in 1997 when police placed him in a locked-down psychiatric unit for 72 hours under the Baker Act following a suicide bid.

Trouble began early, as a 1991 Forbes report (recently reposted by the magazine) called him a “twisted Robin Hood who takes from the rich and gives to himself and his merry band of brokers” with a business model of “pushing dicey stocks on gullible investors”. Yet Belfort managed to keep the plates spinning for close to decade longer — no mean achievement, in purely logistical terms, for a man who stuck his head into a bowl of cocaine and inhaled through both nostrils.

I spoke to him earlier this week.

Above: Leonardo DiCaprio as Jordan Belfort in Martin Scorsese's The Wolf of Wall Street.

CK: You've been to New Zealand before?

JB: It was my first time speaking after I got out. It was 2010. It was terrific.

And it’s so ironic the movie ended in New Zealand [the final scene of The Wolf of Wall Street shows Belfort delivering a sales seminar to a small, dour-looking crowd in NZ].

I guess you saw the movie, right?

CK: I did. It did seem a bit like at the end New Zealand was being used as the dupe country. It was a bit like “How low has this guy fallen? He’s talking this dreary room of people in New Zealand?”

JB: It’s so funny because it was completely random. It wasn’t my idea. In the script it was Kuala Lumpur. And then I showed up [for a cameo in the scene, as the MC] and it was New Zealand. So I was like 'Why did you pick NZ?' and Scorsese was like [laughs].

The sort of photo that riles creditors: Belfort posted this pic of himself nd his fiancé about to board a private jet to his Facebook account in July 2013. Critics have asked how he can live in a house on LA's Hermosa Beach (swanky by most people's standards, if not close to the Wolf's previous $US27m New York digs).

CK: Did you have a lot of say over how you were depicted in the movie?

JB: I had a lot of say over the parts that they wanted me to have a say over, but I didn’t have a lot of say over the parts that they fictionalised, that I thought … that I didn’t like.

But you know, I loved the movie, and I accept the good with the bad. And I understand most of what they did, ficionalising, because they only have three hours to get the point across, and they’re trying to get certain emotional reactions from people. There are some things I thought could actually have been better, or filmed in a different way – more realistic. But I’m not Scorsese and he’s the master, so you’ve got to go with his gut, right?

Belfort today: Clean, sober, stilll chased by the government.

CK: What’s an example of a bit they fictionalised? [They being Scorsese and screen writer Terry Winter]

JB: Well one example I though really could have been more compelling is that if you recall the beginning of the movie, I go down to Wall Street as this idealistic young guy and I have this meeting with Matthew McConaughey who was my boss [in real life, Mark Hanna old-money trading firm old-money trading firm of L.F. Rothschild. Hanna ended up working for Belfort at Stratton Oakmont, an ironic twist ignored in the movie].

I’m refusing drugs, and I’m saying we should make our clients too and he’s saying ‘no’ and he shatters my bubble. That’s kind of the way it was. But then in the next scene, they have me in a strip club doing cocaine. But that’s not at all what it was like. My descent into drugs and that kind of insanity was like two years later. It was a very slow, insidious process. So I think in some respects when people went to the movie they were like, wait a second, this guy’s out of his mind. He’s this nice young guy who got corrupted in four seconds.

And that just wasn’t true. When I started my firm, it was totally legit and no one was losing money, there was never any intent to lose people money. That happened after about a year. And then – and I’m the first person to admit it – as we say in the US we took a left turn at Albuquerque and things went bad. But that certainly was not the original intent and I thought it would have been more compelling if they showed the slower decline.

That would have been indicative of not just my story, but what happened with the global financial crisis. You see [reports of] all these Ivy League bankers running amok. But how did it happen? It was a slow decent into ethical bankruptcy. That would have made a more compelling story. But that’s the route [Scorsese and Winter] chose and I accept it.

In his book, Belfort claims his "rathole" scam (where a third-party, or nominee, is used to secretly hold shares on your behalf) is common practice on "respectable" Wall Street. He tells NBR he was singled out because of his flamboyant behaviour and "not being part of the club".

CK: You’re talking about ivy league bankers running amok and of course some of them did get into trouble after the GFC. But do you think you were targeted in the 1990s because you were so flamboyant with the strippers and the drugs and what have you?

JB: I put a bulls eye on my back, no doubt about it. And also of course, because I wasn’t part of the club.

Like, here’s an example – Bernie Madoff. He was doing his thing [a Ponzi scheme] in the 1990s and he was chairman of the Nasdaq and saying that I’m a bad guy. And it was happening at the big firms. Merrill Lynch bankrupted Orange County. I’m not trying to say I wasn’t even. I never try to minimise my actions or mistakes. It’s pretty ironic.

[By not being “in the club” he means being apart from the Wall Street establishment. Stratton was both physically remote, out in the ‘burbs, and failed to conform to Wall Street norms. But his autobiography, while never sentimental or making excuses, is replete with references to Wall Street as a bastion of the WASP establishment. Though of course it is not exclusively so. Madoff and other insiders from Belford’s heyday didn’t hail from country club-friendly ethnic backgrounds - CK]

But then again, as you say, you had the tell-tale signs that things were going on: the hookers, the drugs, the 170-foot yacht.

Let’s just say that if I could do it all over again I would have lived a far less flamboyant existence.

Belfort smuggled around $US20 million into Switzerland, strapped to the wife of his Quaalude dealer, plus various members of her family (as depicted above in a scene from Scorsese's film). The money was stashed in secret bank accounts held in the name of an in-law — an aunt of Belfort's wife. The aunt died suddenly after agreeing to participate in the scheme, but her death proved little obstacle, thanks to a second Swiss contact Belfort employed, aptly known as The Forger. The gambit came unstuck when Belfort's Swiss banker was arrested during a visit to the US for an unrelated scam, then blabbed to authorities..

CK: Your suicide attempt and being locked up for three days in a psychiatric unit [under the Baker Act, meaning a judge deemed him a threat to himself and others]. Why was that not in the movie? It seems very much in Scorsese territory?

JB: I didn’t tell them to de-emphasise anything. I never told them what they couldn’t put in.

I thought that scene would have been great.

What happened was, they fictionalised the whole scene at the end where I had the struggle with my wife [in real life, a Tony Veitch-esque episode that saw the sleight-of-stature Belfort kick his wife down some stairs during a fight. In his book, he says his wife often hit him or threw things at him].

Leo [Leonardo DiCaprio, who plays Belfort in Wolf] called me and said ‘I punched your wife in the stomach’. That was totally made up.

When the movie came out, my ex-wife and I took our kids to see it, because we wanted to show them together that that never happen. I never wound up and whacked my wife in the stomach. I never did that or anything like it.

I did – the day I got sober after three months of not sleeping and being whacked out on cocaine and everything else, I did grab my daughter [After the fight on the stairs. Belfort, stoned, tore off in one of his cars with his daughter in the front seat, forgetting to buckle her in. He crashed into their home’s front gate. She wasn’t hurt - CK]. And again, this is something I’ve completely reconciled in my mind. I can’t feel bad about what I did before the day I got sober, you know what I mean. I was a frickin’ maniac. On the stairs, my wife jumped up to grab me and I kicked out, and she fell down a couple of steps, but it wasn’t like I wound up and knocked her in the stomach with my fists.

Of course it’s bad. I’m not trying to say what I did wasn’t terrible. But it was like that; like I wound up like a sober guy and banged her in the stomach. And that whole scene was the predecessor. I felt so bad that I took the overdose and tried to commit suicide [by knocking back a bottle of morphine pills with Jack Daniels] and ended up for three days … they cut out the whole rehab scene.

I went to drug rehab. And they replaced that with when the yacht sank, that was my moment when I got sober [in real-life, Belfort’s 170-foot yacht did sink in high seas off Italy. He, his wife and friends had to be helicopter rescued in dramatic circumstances, but incident did not dent his hard-partying lifestyle.]

But Marty’s first cut was four hours – and that was without any rehab stuff. At the end of it, there’s only so much of the story they can tell.

Belfort, present-day, pictured with his fiancé and an assistant.

CK: I was also curious they left out that you went to work for Steve Madden [the Steve Madden Shoes IPO was handled by Stratton Oakmont].

JB: That was one of the things I absolutely hated about the movie. They fictionalised where I gave my farewell speech then I say “I changed my mind, I’m staying.” That’s completely false. I left [in 1996, Belfort reached an agreement with the Securities Exchange Commission that involved him agreeing to leave the company].

I went to Steve Madden Shoes and was instrumental in it going from $US20 million [revenue] to $US150 million. It was not so much I was an expert in the shoe business as I brought in the right management. Steve was a brilliant designer of shoes, but it was a mom-and-pop operation. I had this guy Elliot Lavigne - a very gig garment center guy – create a plan that we used to take the company to the next level.

I understood why they left that out. I didn’t argue with it because the firm was the backdrop of what was going on and they didn’t want me to leave the firm.

I think they also wanted to show that basically I’d completely lost my touch with reality and I’m like “F*ck you, the government,” but that just never happened. But again, you take the good with the bad.

CK: From your book, it seems you were more or less trying to make an honest living at Steve Madden Shoes and get the company into shape with the manufacturing logistics and the department store deals, and then he turned around and started selling the shares he held under the nominee arrangement [Madden secretly, and illegally, owned shares in his company on behalf of Belfort].

JB: Yes, I also bear some responsibility. Not just that he tried to rip me off for money but that was when I was really starting to spiral out of control with drugs.

In his defence, he shouldn’t have tried to do what he did with the money, but … that was the time I had back surgery for spinal fusion and I was really unhealthy. I was actually taking the ‘ludes to kill the pain as well, and it also served as the greatest excuse to keep doing them. It’s quite complicated. I really was in pain. That bit was left out of the movie. Then again it was also the world’s greatest excuse not to get sober.

CK: When Steve started selling shares and ripping you off, do you think it gave you a degree of empathy with the people you’d ripped off over the years?

JB: [Pause] Good question. Um, you know, at the time it didn’t because I was so drugged out. It was the height of my addiction. It was the two months prior before I got sober.

If you notice in the book, my inner dialogue – it almost borders on insanity. When I’m going through the Steve Madden thing in my mind I’m purposely trying to show people the insanity when I was suing him [revealing the illegal nominee arrangement in his bid to retrieve tens of millions] and I felt like I was invincible from the cocaine.

But the thoughts are almost like a mad person’s thoughts.

So I wasn’t feeling empathy for anybody at that moment, I’ll just be honest with you.

If I’d thought about then yes, I’d have thought it was very ironic. I probably would have said, “Jesus, being on the other end of the whole thing is pretty frustrating, you know?”

CK: I asked readers if they had any questions for you and the most common was: how much money did you make from the book and the movie and where are you at in terms of paying restitution:

JB: Yeah … yeah. Well, I’m not making any money on the books or the movie, and I’m also in the process of announcing a major new tour.

And when I say major I mean like a mammoth US tour. I'll be doing like probably 25 of the biggest cities, with audiences of probably 20,000-plus. And I'm giving 100% of all the profits back to [Stratton Oakmont] investors and I hope is that between that and the book royalties everyone will be paid back in full within the next 18 months to two years. That's my goal, and I think I can reach it. I'll announce it within a week. I guess you could call it 'The final redemption tour' where I pay everybody back. [See more of Belfort’s comments on restitution in NBR’s earlier story here]

CK: Are you still sober?

JB: I’m still sober. I drink alcohol, very occasionally. Alcohol was never my issue. When I first got sober, I didn’t drink for nearly seven years. Now I drink a couple of glasses of champagne a week. Maybe one Martini every two weeks … I’m just not a drinker. But I haven’t done drugs in 17 years.

CK: Do you feel guilt?

JB: I'll feel a million times better when I pay back the money, because I still feel terrible about it.

But I don’t feel guilty about it because guilt is a very destructive emotion.

I do feel remorse, which is the active form of guilt where you try to do something about it.

Feeling guilt just hurts you and your family, verses remorse which is where I’ve internalised it, I’ve accepted the mistakes I’ve made, and now I’m trying to right the wrongs.

Thankfully, the movie created the opportunity for me where I can try to do that.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.