Let’s have a look at the Greens' proposal to reduce electricity prices.

I’m entering this as a sceptic, but also as founder of Powerkiwi (join!).

Powerkiwi sold a good amount of power on Powershop last year – 140 million units (KWh), or enough (at 8000 kWh/house/year) to supply over 17,600 houses.

I know a little bit about the industry, but am not at all an insider at all in the larger game.

But here goes:

"Our power bills are too high. While average power prices in the OECD have decreased in the past 20 years, in New Zealand they have gone up over 70%." - Greens

I don’t think that’s at issue here. Let’s dig into the industry.

Supply

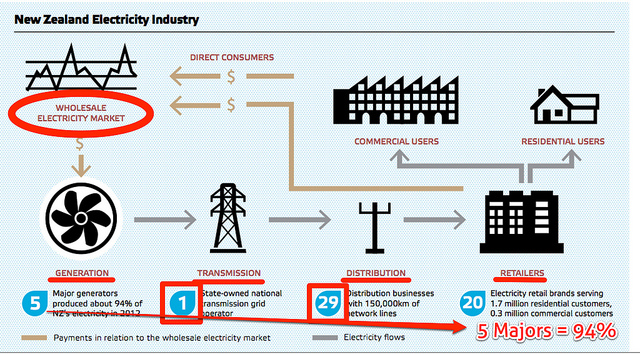

Enter a nice chart I got from, err, some prospectus. (Ignore this if you are an investor from the USA.)

The red marks are mine. There are five major producers (and 8 smaller ones), 1 national lines company, 29 local lines companies and a bunch of power retailers, of which Powerkiwi is one (though we are probably counted as part of Powershop, which is part of Meridian, which is owned by taxpayers):

Click to zoom.

The national lines company, TransPower, and each of the local lines companies are monopolies, with the lines companies alone estimated to be worth $8.8 billion by the Commerce Commission in 2012.

TransPower is government owned, while the lines companies have diverse ownership, with some owned by consumers, others by local government, and seven have at least some investors involved. Those seven are collectively large – 56% of all customer connections are served by them. And those investors are motivated to have healthy prices and profits. Lines companies are a great business to be in – they regularly put their prices up, and there is nothing the retailers or end customers can do about it, although there is ComCom involvement with investor-type lines companies.

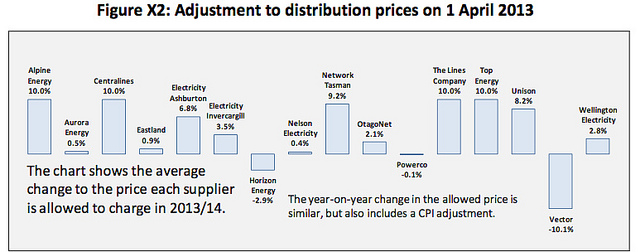

Here’s the Commerce Commissions’ ruling on lines company price rises for 2013:

Click to zoom.

I guess Vector is making too much money right now. It’s nice for a business to have a price setting regime that ensures they make a profit each year, unlike regular businesses who have to face up to pricing risks and competition. Generally shareholders accept much lower returns on equity for these utility businesses. However Vector, who I am admittedly picking on, had an EBIT to total income ratio of 37% in the six months to December last year, and made net profit of $118m on revenue of $669m.

That’s amazing for a company without real price risk for its electricity business. Most of the recent revenue increase came, they say, from “unregulated technology operations, higher Transpower charges (passed to customers) and price increases on our energy networks”. Yes – a great business to be in, but to be fair they have gas and ‘technology’ as well as electricity.

They distributed 4,312 GWh of electricity in all of 2012, which is over 30 times more than passed through Powerkiwi’s accounts. Their 6 month to December revenue from electricity was $335 million, and EBITDA was $202 million, which is a incredible level of return of 60%. We should also add back the very real cost of depreciation and associated maintenance work on their infrastructure. The grew their smart meter numbers by 38.5% to 438,419 meters, for example, and this investment is not counted (I am guessing) as an expense. Any analyst looking at this sector should be ignoring the EBITDA numbers, but sadly the capital expenditure and depreciation numbers are not broken out by area spent. Regardless, any reasonable assumption for those numbers leaves an absurdly high margin for their electricity distribution business.

Going back in time this article states that the ComCom saw the distribution costs in NZ rise at 5% above inflation from 2008 to 2011, but apparently capital spend more than made up for that.

Transpower pricing is regulated by the transmission pricing methodology which is approved by the Electricity Authority – and that methodology is under review, and prices are likely to go up, perhaps significantly, beyond 2015, conveniently distant for Mighty River Power’s IPO.

All of these lines costs are passed to the retailers, who in turn pass it straight to us all, as consumers. It’s itemised on our bills as a daily or monthly rate (and Powershop’s and Powerkiwi’s pricing includes it). So when the Commerce Commission says raise your price to the lines companies, they do and we all pay. We can bet that the lines companies understand very very well what they need to do with their businesses and how to present themselves to the ComCom to make sure they are allowed the best price treatment each year. But competition is not coming anytime soon – as only one physical line per house makes sense – so something like this regulation needs to continue.

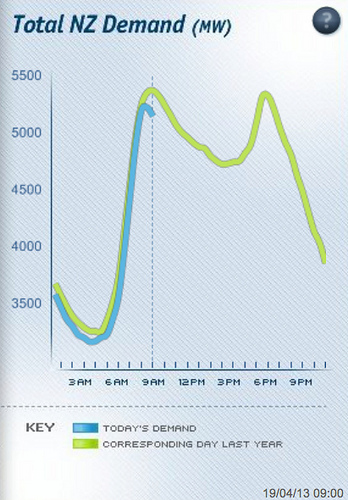

Let’s move to the wholesale electricity market, where energy is bought and sold and prices vary through the day, peaking in the evening when we all get home, and seasonally peaking in winter when it is cold. Here’s a chart of demand for today (Friday 19th April, 2013)

.

.

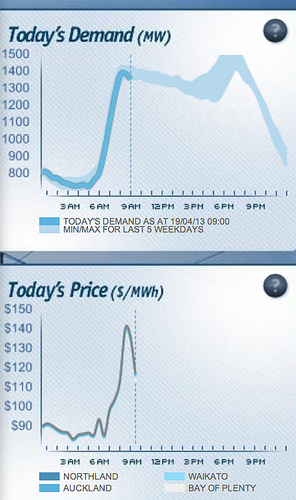

The price varies according to the lake levels, and according to what power stations and lines are offline for planned or unplanned maintenance. There is a market for retailers and large businesses to buy financial instruments to lock in a price for a period, or they can expose themselves to the market. Here’s today’s chart so far for North region:

That’s a lot of volatility, and as a large buyer exposed to the market you’d like to be able to vary your demand according to price. Sadly for most we cannot do that, but therein lies an opportunity for later.

Retail Pricing

Most retailers, except for PowerKiwi and Powershop, set one price for consumers for the year, and it has to, by definition, be well above the average price set in the marketplace. The biggest period of use, winter, coincides with the largest use, and so the price everyone pays reflects those winter prices. The retailers are, however, already buying in bulk and saving, using a combination of spot and longer term contracts. Retailers cannot afford to get this wrong, trading electricity with negative margins is a quick way to lose a lot of cash. So they give themselves a buffer, and so consumer prices are higher, but at least they are not subject to hourly change to potentially astronomic levels.

Meanwhile many customers are simply on a more expensive plan than they could get today at another provider, and while it does pay to shop around it’s a real pain in reality (unless you switch to Powershop of course). All of the retailers have a profit motive, despite some being government owned, and so all are seeking to maximise the return to shareholders through the right combination of buying, market share and pricing.

So the wholesale price of electricity varies all the time, often wildly so, the price to consumers is fixed, and the lines prices, which are passed on to consumers, are fixed and steadily rising.

And therein lies the rub. The real money is not made at retail, but in the lines and at the other end – generation. The business of electricity generation is a great one if you own certain types of costless assets. And in NZ companies do – there is a huge percentage of renewable power, where the inputs of sun, wind, rivers, lakes and geothermal energy are delivered essentially free.

"The problem is that all generators are paid at the cost of running the most expensive power plants. Even though most of our power plants were built decades ago with public money and cost less than a cent a kilowatt hour to run, their owners pocket more than 10 times that amount" - Russel Norman, Greens

This is true.

The price the owners of dams receive is nowhere near the marginal cost of producing that power. Instead that price is closer to the price required to build and run profitably the last power station that was built. By definition the last power station is the most expensive ever per unit of electricity, else someone would have built a cheaper one earlier. (It’s not that simple, but roughly so). That price has to take into account all of the pain and time and costs of building and then running the station. It’s it’s a solar plant, then the loans taken out to build the plant need to be paid back, maintenance paid and so on. Plus the solar plants are not on at peak times, so they will always receive lower spot prices. If it’s a thermal plant then the inputs of gas or coal need to be purchased forever, and the price will vary according to those input prices. In general they only switch on when demand is high – it’s expensive to run.

So the peak market price is set by the latest plant, and the price in energy unit terms per plant naturally rises over time. And companies that own renewable assets built in the past make lots of money. Turns out some of Muldoon’s Think Big did work after all.

"Governments and private investors have used the electricity market as a stealth tax on our economy and have pocketed billions of dollars." Russel Norman, Greens

The problem here is that the income to government offsets other sources of income, like income tax, and related to that the money the government accounts will receive from the Mighty River Power float is a reflection of that profit. However that excess profit is also used to invest in new infrastructure, the free power generators of the future. It’s important to remember the lessons of Telecom’s underinvestment (with short term profit-seeking shareholders) and indeed the sustained underinvestment in electricity infrastructure that led to the price rises and the dreadful Auckland power cuts. We are in a much better situation now. I’m not saying that the 100% profit motive and rising prices was perfect for Might River Power and others under Government ownership, but if not then the entire market including competitors would have less incentive to invest in new plants. The current reality of a series of new, green, power stations and improving infrastructure is wonderful, but we got there through the profit motive and market pricing.

Some trends to consider

The technology part of the cost of generating solar and wind power is coming down, still high, but coming down over time. We are also getting smarter about extracting electricity with geothermal power. Dams are too hard though, as tolerance for the ecological change is very low. Overall, the next few power plants look to be renewable ones, which is great as their marginal cost to produce electricity is very low.

On the horizon is the gradual and then mass take-up of micro-energy generation at home, as solar panels (mainly) become cheap enough to place on every house. The electricity generated can be directed to the house, to a local community or back into the national grid. This alleviates day-time demand from the large power plants, and allows the dams, for example, to save their power until the more lucrative night-time rush. All these serve to lower the cost per unit of energy, as do the switch in lighting technology, better insulation programs and other energy efficiency measures.

Offsetting that cost pressure will be the gradual, and welcome, switch of the vehicle fleet to predominantly electric powered cars. They are not quite viable for most people, but it’s very clear where the trend is going. Some time within the next 10-20 years it will be silly to buy anything but an electric vehicle, as the cars will be faster and cheaper than those which internal combustion technology can deliver. Driverless cars will reduce consumption further. All those cars will need electrical power, and so that will increase overall demand. On the other hand all those cars will have batteries, and that storage is a great way to smooth out power consumption, taking power when it is cheaper perhaps from a household’s solar panels and returning it to the household or grid when it is more expensive at peak hour.

Peak hour is what our electricity generation and transmission system is built for – with a safety margin of course. Smooth the peak demand and the more expensive to operate power stations will get used less, and the average price will fall. So the cars in garages at home or work have a potentially interesting role to play. Imagine getting cheap power at work for your car, taking the car home and partially powering your house that night. Now that’s a nice perk.

But taking all of that into consideration, here’s what government projections for demand look like:

Electricity Authority: Electricity in NZ 2011

Yes – a steady rise in demand. You could argue that the curve will change, but I find it very difficult to justify changing a curve when I see a clear trend like that. It seems fairly clear that demand will continue to increase, and thus new plants will be built and pressure on prices will rise.

So let’s turn to the Greens’ recommendations:

Firstly, establish a single buyer that will negotiate cheaper power prices for all of us

Secondly, deliver cheaper power by giving each household a block of low cost electricity every month

And third, strengthen the role of energy efficiency and green energy within our electricity system.

It’s good to see them start the conversation, but I believe this breaks the market paradigm and moves us towards the lines company model of ever increasing profits without risk to the retailers.

The first recommendation ignores the fact that we already have three very large government owned buyers – the Government owned power companies. They can assert market power as it is, and can do so through long term contracts. So we should keep one or two energy companies owned by the government and encourage or mandate them to set the standard in cheap power and great service. However part of getting a long term cheap contract is often that you are using power in low-demand periods, and are able to shed load during peak hours when the retail price is high – as many aluminium smelters can do. That does not work with retail, not at the moment, as retail pricing is fixed throughout the year.

The second recommendation does not reflect the fact that electricity prices vary by time, and a block of power is currently priced at the weighted average demand x price for the month. If a large generator signed up to this deal that means they would not be able to turn their supply down or off when, for example, the lakes were low, as they would lose money by being forced to buy power on the spot market. The system as a whole could suffer if the lakes were drained for some customers, as we may not have extra generating capacity when we need it later.

Customers meanwhile would meanwhile be exposed to much higher market prices for the bulk of their purchases (8000-3600=4400 units a year) as the money that disappeared from companies would need to come from somewhere else, to pay for their continued investment in infrastructure, and for their cost of capital. That means higher prices for all of the bigger users as well, especially businesses. I have a interest in an electronics manufacturer who would become a bit less viable as a result. It could all sort of work if enough demand was smoothed across the day, but that requires other things to happen, as discussed below.

And finally the money that disappeared from the industry with the first and second points is currently being used to pay to build the largely green power generation and lines infrastructure – so the third outcome could be worse than present. And then there is the business case for new builds – why build a new geothermal plant when the market to sell that power at reasonable prices is gone, or may go in the future when it is deemed “paid off”?

The price of electricity to consumers is made up of generating costs, lines costs and retailing costs. The Greens’ own arithmetic shows a 9 cents/unit energy cost, and 18 cents/unit for everything else. But the Greens’ proposal will push costs to lines companies up as they upgrade their infrastructure to smart grid status – and those fixed daily costs hit lower use consumers proportionally higher than others.

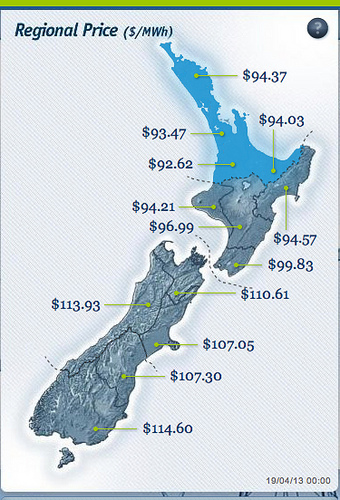

Now that energy cost, as I write this, at 11:45pm, is actually higher in the spot market than that 9 cents quoted, and likely to be much higher later in winter ($94 per MWh = 9.4 cents/unit – from this handy site). Here’s a map:

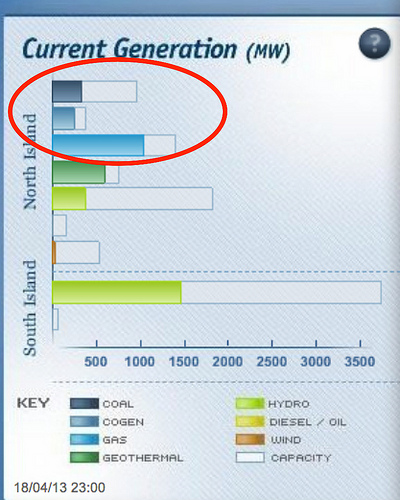

What’s going on? Well, the marginal cost of generating electricity is high because we have coal, gas and cogeneration plants all on the go at 11:45pm, as seen is this chart:

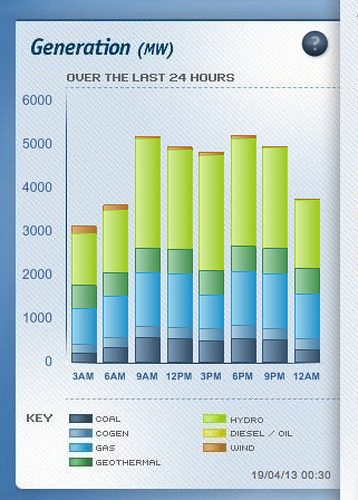

And here is is over the last 24 hours – remembering that blue is expensive:

These thermal plants cost a lot to run, so the price is higher. If we want these more expensive plants to be there when we need them, like today, then we need to make sure they are used enough each year to be economical and that the price is fair.

If we want to build more geothermal, wind or solar plants, then we also need to pay them a decent price so that their investment gets a return. And that return should last forever, not for a limited time.

The green bars at the bottom are the ones that the Greens’ are probably most upset about – that’s South island hydro dams pouring energy into the grid at essentially zero marginal cost. I’m going to guess that a lot is going to Tiwai.

Overall

I did not support the prospect of the IPO of Mighty River Power, and nor did I place a vote for my National candidate in the last election with the expectation that it would be perceived as supporting that mandate. I also voted for the Green party as I see they temper National well, while Labour had too many dumb ideas and an old guard.

But now that the Mighty River Power prospectus is out it’s been invigorating the capital markets and is in turn hopefully going to make it easier for people in my space of web, technology and design-led businesses to raise money for the next generation of companies. Mighty River Power is a very investable proposition, and indeed last night I did just that – invested.

This bombshell policy threatens to derail the Mighty River Power IPO process, and arguably is in response to the National Party steamrolling this through without regard to the referendum and other obvious signs of public discontent. But it is rough politics, and I would expect more out of Greens at least, who should be demonstrating that they are ready to govern responsibly. It’s a move that if continued for too long will arguably threaten the possibility of a Labour-Green government at the next election.

But let’s not get carried away, and treat it as intended – as a way to start a conversation, and with that in mind here are ten alternative suggestions:

So what would I recommend that govt do?

Firstly, I’d fairly quickly open up the wholesale electricity market to everybody, not just the handful of operators and retailers. It’s very complicated now, and some work is required, but I’d like to see retailers like Powershop (and Powerkiwi) able to aggregate consumers and expose them to the hourly variations in pricing, so that they might adjust their demand to save money. A better market will also allow those retailers and consumers to sell back any power they generate at market rates.

Second, and related to the first, I would make sure that the lines companies and other local suppliers such as meter readers must deal with all retailers on the same basis and on the same easy terms. That means Powershop, for example, would be able to quickly roll out to all markets in New Zealand (like Nelson), and so would other retailers. The mission is to systematically break down barriers to entry, so that the price pressure can remain firm. Some retailers may even build enough customers to buy that dream amount of long term cheap capacity.

Third, invest heavily in the proverbial ‘smart grid’. Minimum requirements for this are to measure generation and consumption of power minute by minute at each location. The network will need to cope with those battery powered cars or home solar panels contributing power, provide for redundancy when major lines go out, figure out who is owed what in real time for consumption and generation and allow consumers to track it all with open data.

Fourth, why not put in place regulations that provide incentives for households, farms and other businesses to install solar panels and other micro generation plants. This could be a loan program, a feed in tariff program or even a mandate for any new property developments and renovations. Preferably it would be all three. The feed in tariff program would make sure that retailers and lines companies take back the power that the consumer generates at a fair price that is related to the price the consumer pays.

Fifth, why not push to make it much much easier for consumers and businesses to switch between companies, and expose the prices offered by companies for all households. Do this by migrating the government owned retailer’ customers to the Powershop marketplace, perhaps splitting Powershop to be independent from Meridian. On the larger Powershop customers could be offered contracts that are annual, daily or anything in between, and the switching and selling costs would vaporise, saving the industry money and making it easier for consumers. (And no more paper bills). This means, for example, that households could choose to manage their consumption to reduce peak time demand and expenses – and that in aggregate lowers the costs for the industry.

Sixth, why not play hardball with our biggest CO2 emitter and electricity user – the Tiwai point smelter. Releasing that baseload electricity into the market will push the prices down for a while.

Seventh why not put that windfall money from the profit from the current government-owned dams into creating new green generating capacity, and to subsidising government so they can directly help poorer families through social welfare benefits and through efforts like the Greens’ housing insulation program. Make it a little more explicit than what happens now, including putting a mandate on Mighty River Power for investment in green power (it would likely change nothing in their plans), and including the lines companies. And yes, this is happening now, but can be even faster.

Eighth, never sell those other lines companies – keep them in the trusts and regional councils. They are a license to print money.

Ninth, let’s go ahead with the Mighty River Power sale, but make sure that NZ retains the majority shares, as the plan is. The sale is a done deal, but let’s not be hasty about Meridian, although the case for Solid Energy being in taxpayer hands is far less apparent.

And tenth, let’s think about splitting the generation and retailing arms of the remaining two government owned power companies, keeping the renewable generating assets and selling the rest. That will change forever the balance of power in the wholesale market.

Entrepreneur Lance Wiggs is a backer of Powerkiwi, a supplier to Meridian-owned Powershop, among other investments. He blogs at LanceWiggs.com.

Sat, 20 Apr 2013

Free News Alerts

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.