New Zealand has always had progressive marginal rates for personal income taxes.

When first introduced in 1892, personal income tax was a simple three tier system, ranging from 0% for income under £300 to 5% on income over £1000 (a shilling per pound).

By 1909, this had developed into a complex scale encompassing 10 levels.

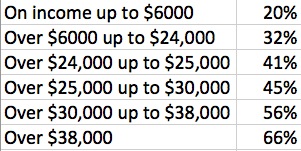

Much steeper rates applied in the 1984 year. Back then, my main source of income came from delivering newspapers after school – so most of the rates weren’t particularly relevant to me.

More mature readers may remember the following scale of tax rates:

Thank goodness those rates no longer apply. At today’s minimum wage of $14.25, a full-time worker would be nudging the second highest tax rate.

Of course, the tax system was a different beast back then. GST and FBT were but a developing twinkle in Roger Douglas’ eye.

Things were also a lot cheaper in 1984 than they are today and people generally earned less in nominal terms.

The Reserve Bank has an excellent inflation calculator on its website. Applying it to wages, the calculator shows a 1984 top-bracket salary of $38,000 is equivalent to a salary of $138,700 today.

The closest we ever came to a flat tax during my working lifetime was a two-tier approach that was introduced in 1989. At that time, tax applied at a rate of 24% on income up to $30,875 and at 33% on income earned over that amount.

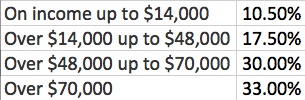

Today’s personal rates of tax are:

Those rates have applied since April 1, 2012. They came after a couple of years of reductions, following the “tax switch” with GST in 2010. This will be the third tax year in which these rates are used.

Bracket creep (or “fiscal drag”) occurs when inflationary pressures push taxpayers into higher tax brackets. Often, salary increases occur as an inflationary “mark to market” adjustment.

A good recent example is the income tax bands that applied throughout most of the 2000s. During this time, the average marginal tax rate increased from 26% in 2000 to 31% by 2008. This has been attributed not only to the introduction of the 39% rate in 2000 but also the effect of bracket creep.

In a flat tax environment, the more a person earns, the more tax they pay. Progressive marginal rates mean wage increases will push earners into higher tax brackets.

That means they will pay “more than more” tax, leading to a decline in after-tax income in real terms and an increase in average marginal tax rates.

In other words, the tax-take increases without having to put up rates.

Fortunately, New Zealand has enjoyed a low inflation environment in recent years. However, favourable economic forecasts indicate inflationary pressure is starting to build, as happened in the Reserve Bank’s recent adjustment step to the OCR. That will make inflation adjustments to the tax brackets more relevant.

While the government’s adherence to fiscal prudence is admirable, and it’s been made clear there will be no election year “lolly scramble,” regular adjustments to the tax bracket thresholds will also ensure there is no unjust extra layer of icing on the government’s surplus cake.

Geordie Hooft is a partner, tax and privately held business at Grant Thornton New Zealand

Sat, 12 Apr 2014