BOOK EXTRACT: Legend

Legend - From Electric Fences to Global Success: The Sir William Gallagher Story by Paul Goldsmith.

Legend - From Electric Fences to Global Success: The Sir William Gallagher Story by Paul Goldsmith.

BOOK EXTRACT: Legend - From Electric Fences to Global Success: The Sir William Gallagher Story by Paul Goldsmith (HarperCollins, $45)

The Gallagher Group, headed by Sir William (Bill) Gallagher, was formed in a Hamilton shed in 1938. Today it employs more than 1000 staff across 130 countries, and the NBR Rich List puts the family's wealth at $165 million. The chapter extract below picks up the story as Sir William attempts to crack the closed European market.

Legend will be launched on March 20 at an event hosted by the American Chamber of Commerce at AUT University's new Sir Paul Reeves Building.

The Electric Fences Take Over: 1977–85

Late one dark, stormy night in the spring of 1977 the Dijkstra family was sitting around the fire at its farm in Holland’s far north when they heard someone tapping at the window. ‘Who the hell could that be?’ they wondered. No one knocks on the window in Holland. The Dijkstra farm was in the middle of nowhere, in the countryside beyond Groningen; it was raining, there were no lights outside. Dutch visitors would simply enter the out-buildings and make their way inside.

As the family let the bedraggled stranger in, he introduced himself as Bill Gallagher. One of the Dijkstras had written to him, and now he was here from New Zealand to talk about his electric fences.

The Dijkstras’ interest in Gallagher electric fences had been sparked a few months earlier by a memorable shock. Dooitze Dijkstra had been scouting for pedigree sheep in Scotland, and wanted to cross an electric fence to look at some lambs. He saw it was covered in long grass and from his knowledge of electric fences was certain that it would have long since shorted out, offering no threat. Swinging his leg over the wire he received the shock of his life in a most inconvenient spot. As his son Erik says, ‘Totally impressed by what had hit him, my father was anxious to discover its cause. It was simply not possible that he’d been zapped by a fence so covered with grass.’ He found the farmer and was shown the Gallagher BEV II energiser. Dooitze Dijkstra returned to Holland without his sheep, but he had two Gallagher energisers.

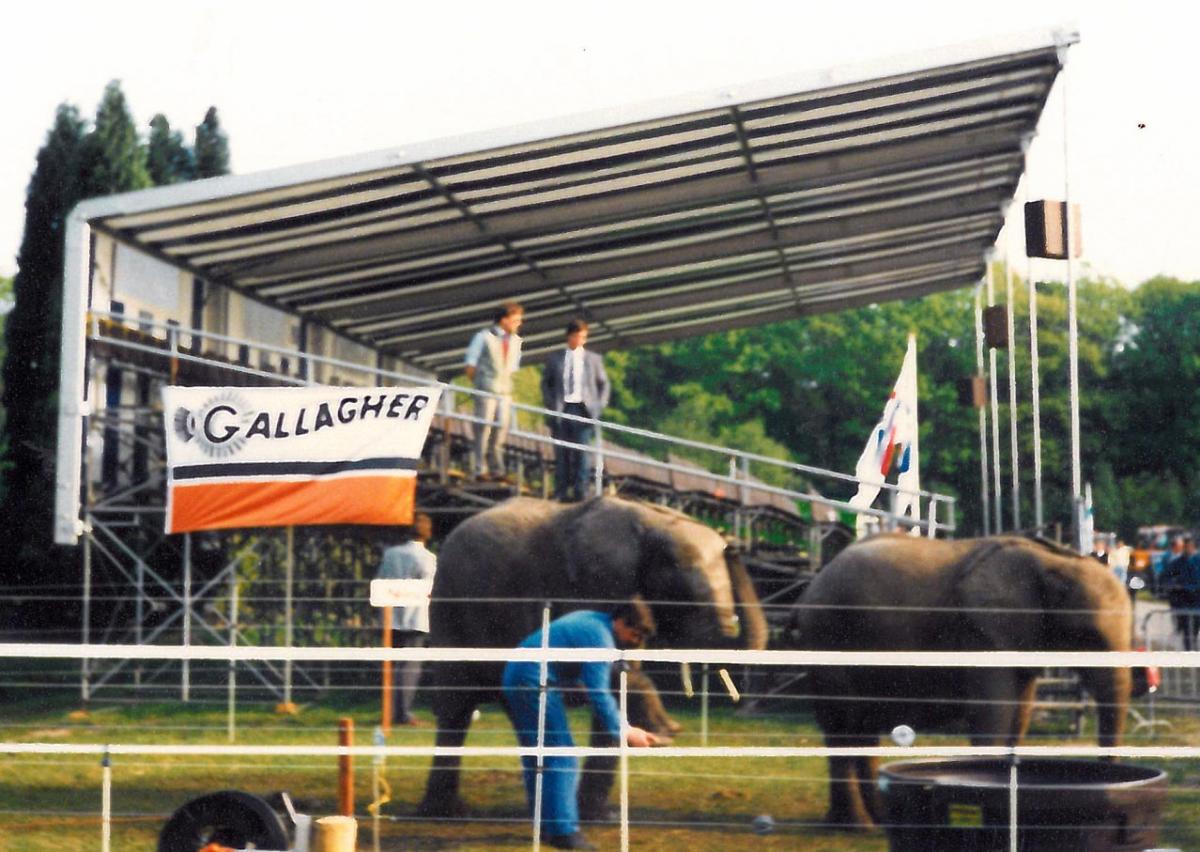

ABOVE: Erik Dijkstra used circus elephants to demonstrate the power of the Gallagher electric fence.

Back home, he showed his new purchase to his brother-in-law and business partner John Veldman. Immediately they saw a business opportunity. Having started off as farmers with 100 hectares, which was quite large for a Dutch farm, Veldman and Dijkstra had branched out into various entrepreneurial schemes over the years. They traded sheep and had a meat works. Knowing that the leading Dutch electric fence, Koltec, was weak and ineffectual the moment foliage grew around it, they were sure that this new and much more powerful beast would find a ready market among Dutch sheep farmers, who faced considerable costs with their traditional fencing.

ABOVE: Much of Bill Gallagher’s time was spent attending agricultural shows around the world. Here, in 1982, he is with Bernd and Martha Allie, Gallagher’s German distributors.

Looking at the label, they saw the energisers came from New Zealand, a country about which they knew nothing. They wrote to Gallaghers, asking for more information. And it was in response to that letter that Bill Gallagher turned up on a chilly April night. On his way back to New Zealand from London, he had flown into Amsterdam and hired a car, but driving north he had been so overwhelmed with tiredness that he had pulled over for a sleep beside the road. Hence his late-night arrival.

Inside, he started telling the Dijkstras all about the company and its origins, and why its energisers were so good. Dooitze’s English wasn’t so good then, but Erik and his younger brother Meindert had enough to gain a handle on the story. Another visit from Gallagher followed in October, and Veldman & Dijkstra took the distribution rights for Holland.

ABOVE: Even the Swedes were enthusiastic users of the Gallagher energiser.

Erik, who was not long out of school but already well equipped with a strong personality and infectious sense of humour, was given the task of growing the enterprise. In January 1978 he flew to Hamilton to spend three months learning about the business. He recalls: ‘Bill had built up the story about Gallaghers’ fame quite high, so when I arrived at Auckland airport and the officials asked what I was planning to do in New Zealand I said confidently I was going to see Gallagher. “Who? What?” they asked me. I thought everyone in the country would know him. Eventually they found Gallaghers of Kahikatea Drive, Hamilton, in the phone book. So that was a disappointment; he’d somewhat oversold his fame.

‘I got over that shock and then started my education in fencing and efficient New Zealand farming, including my “masters of fencing” from Ben Hickey, a Gallagher distributor from north of Whangarei who put fences on the most amazing hillsides. New Zealand was so isolated; I almost had to ask permission from the operator to ring Holland. They’d ring back an hour later with a connection, then once you were on you finished every sentence with “over” and waited for the reply, all costing $15 a minute.

‘But I loved it. I’d been thinking about studying economics when I returned to Holland, but by the end of that summer I’d forgotten all about that, I was so thrilled by what I’d seen — the strip-grazing systems that applied in New Zealand, made possible by efficient electric fencing. I felt like a disciple returning home to preach the new gospel.'

It wasn’t a bad effort for a comparatively small part of Europe. In real terms, exports to Veldman & Dijkstra in 1984 were the equivalent of Gallaghers’ entire electric fence exports in 1977.

The Dutch story was replicated in many other countries around the world over the same period, usually, but not always, on a smaller scale, and it was these business relationships that propelled Gallaghers forward in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Bill Gallagher junior summed it up in a 1984 speech: ‘Even when a product is made and is working right, the job is not even half complete. The largest part of the money and a considerable amount of the effort is required to place the product in the hands of the end user.’2

And the best marketers of electric fences, he had found, were local people with a farming background, who happened also to be dynamic entrepreneurs. The trick was to find these people. A large measure of Gallaghers’ success over these years lay in Bill’s impressive hit rate in finding excellent distributors in a range of markets, who themselves were powerfully motivated to grow the business rapidly. With the demand for Gallagher energisers generated by these people Gallaghers could genuinely claim to be a global leader in electric fencing by the early 1980s.

The company’s figures spoke for themselves. Sales of $2.7 million in the year to March 1978 ($16.5 million in 2012 terms) grew to $20 million in the year to March 1984 (around $60 million today). Meantime, a $202,000 after-tax profit in 1978 (equivalent to around $1.2 million in 2012) was transformed to $2.2 million in 1984 (around $6.5 million today). Growth had been reasonably steady, although it had surged in 1979, when the company had once more been ‘playing doubles’.

At the same time, the shape of the company was changing significantly. Almost all the growth after 1978 came from Gallagher Electronics, the electric fence side of the business. Gallagher Engineering, the agricultural machinery business, stagnated. While its turnover doubled between 1978 and 1984, that only just kept pace with the rapid inflation of those years. By 1984 it was contributing only 15 per cent of the group’s turnover, most of it in New Zealand, and less than 7 per cent of the profits. Meantime, the electric fence business had grown in scope. Accessories — from hardwood fence posts to plastic insulators and voltmeters — had become increasingly important, particularly in New Zealand. At home, energisers accounted for only 15 per cent of the turnover; abroad it was closer to 50:50, energisers to accessories. Gallaghers wasn’t just selling electric fences, it was marketing animal containment systems.

If those were the broad commercial trends of the period, the constant was the continuance of a highly supportive local regime. New Zealand government assistance to manufacturing exporters was at its zenith, having gone up another notch in 1978, which an increasingly worried National government had dubbed Export Year. Until then the combination of increased export incentives, export market expenditure, investment allowances, generous depreciation rates and other schemes meant that the company had not paid any substantial tax for several years. Now, in 1978, a tax credit scheme was introduced which made cash payments for increased manufacturing exports. Twenty per cent of increased exports were non-assessible for tax, so if your exports increased by a $1 million, $200,000 was non-assessible for tax, resulting (with a 45 per cent company tax rate) in a $90,000 tax credit. The beauty of the scheme, from the point of view of export companies, if not other taxpayers, was that if the company’s tax bill was zero after all the other factors, then a cheque for $90,000 would arrive in the mail.

This was magic for Gallaghers in 1978, which otherwise was not a great year. Gallagher Engineering actually lost $11,000 for the year, after sales in New Zealand fell for the first time in more than a decade and stiff competition in rotary hoes in Australia had sliced margins. Gallagher Electronics’ profit, meantime, was a modest $40,000. However, a cheque for $175,000 from Inland Revenue transformed the situation, hoisting the group’s after-tax profit from $29,000 to a much more acceptable $204,000. A crash in the Queensland sugar cane industry fouled things up the following year, but in the early 1980s the company was receiving cheques from the tax department equivalent to negative tax rates ranging from 20 to 45 per cent.

It was a wonderful period to be a New Zealand manufacturing exporter. But it didn’t take much imagination, given the country’s slide into chronic budget deficits, financed by ever more desperate overseas borrowing, to see that the good times couldn’t last forever. Bill Gallagher’s response, in good farming tradition, was to make hay while the sun shone. He tore about frantically trying to grasp as much territory as possible while conditions favoured him, and before the competition had a chance to catch up or fight back.

Having discovered that shipping to Australia was often more expensive than shipping to Europe, he felt no constraints in casting his net far and wide. The basic strategy that evolved has been dubbed the ‘sow and reap’ approach by one commentator.3 Working on the philosophy that ‘everywhere is on the way’ if one is travelling between New Zealand and Europe, Bill called in on new countries on every journey, finding local entrepreneurs in each place who were prepared to have ‘their own skin in the game’. He didn’t spend money on market research or any such extravagance; he would go to agricultural field days and shows, talk to a few people and then take a punt. Then the new distributor was left to stand or fall on their own account. Some stood, some ran, some fell, and Bill would focus his attention on those who were promising, visiting them regularly thereafter to encourage and motivate them. And as the business took root in a dozen or so markets, a strong global enterprise began to develop.

Bill was cunning in the way he tried to minimise the financial risks of such rapid expansion. He wrote in 1978:

It is extremely desirable to sell the initial consignment to the new agent, thus ensuring his financial stake in the product. The usual approach is for the agent to ask for consignment stock [only paid for if they sell it] and in my experience this is almost fatal, and to be agreed to only as a very last resort. The successful answer in my experience to the request for consignment stock is to give extended terms. The norm is 90 days but sometimes a special initial 180 days could be offered . . . the major advantage is that it puts the agent on his mettle to move the product and not just let more important things take precedence with his time. It is not very difficult to talk the agent into 180 days, as if he does not think that he can sell the product within six months you are probably speaking to the wrong agent.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.