How Britain’s Imperial citizen-soldiers became heroic victims

OPINION: The evolution of Anzac Day as the birth of two nations.

OPINION: The evolution of Anzac Day as the birth of two nations.

The first Anzac Day was gazetted in 1916, one year after the Anzacs landed at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. It was a half-day holiday in New Zealand that was celebrated throughout the country, as well as in Australia and London, as a patriotic rally to honour those who died in battle for the British Empire.

In 1920, Anzac Day legislation made it a national holiday and observance with dawn parades continued until further changes after World War II, when its role was widened to one that commemorated all who were killed in foreign wars.

This was enshrined in the broader definition of the 1949 Act that replaced the one of 1920. But, over the years, public interest had started to fade. The day’s first ceremony in 1946 at the Auckland War Memorial Museum attracted some 30,000 people but, within two years, attendance had dropped to 5000.

The fixed observance on April 25 was also unpopular, as it forbade commercial and leisure activity in the afternoons and ruined two Saturdays in the 1950s. This was liberalised in 1966 and Mondayisation, creating a holiday on Monday when the 25th occurs on a Saturday or Sunday, was introduced in 2013.

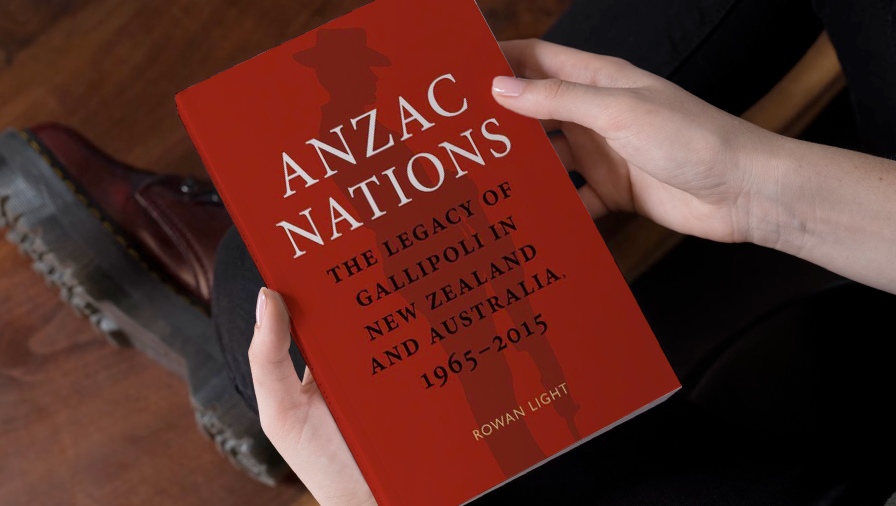

These legislative changes are only part of the roller-coaster history of Anzac Day observances and its role in the national psyche. In Anzac Nations, Auckland historian Rowan Light tracks this phenomenon from 1965 to 2015 in Australia and New Zealand.

Nation-building

As a barometer of nation-building as well as myth-making, Anzac Day reached its nadir in 1965, the 50th anniversary of Gallipoli, when it coincided with protests against New Zealand’s military involvement to resist the communist takeover of Vietnam. The protests later evolved into wider concerns, in step with rising left-wing militancy around the world in 1968.

This was inspired by developments in both Europe and North America, with racial and feminist issues to the fore. “By the 1980s,” Light writes, “feminist interventions were increasingly regarded as shrill acts of aggression, whereas men – both elderly returned servicemen and younger Vietnam veterans – were increasingly positioned as victims of war.”

While political militancy faded, and the 50th anniversary of Gallipoli was a non-event, war commemoration staged a remarkable comeback in the 1980s, largely for economic and cultural reasons.

‘Gallipoli as a place was increasingly invoked as a national totem rather than a set of actual experiences; a feeling rather than an event.’

The rise of independent moviemaking industries on both sides of the Tasman was made possible through financial reforms and globalisation of business. Regulation and licensing of cinemas gave way to more investment in this form of domestically produced entertainment.

Overseas travel also became cheaper and easier for a new generation of Kiwis and Aussies to explore places where their ancestors had died.

‘Cultural memory’

Light records that movies gave “new shape to the cultural memory” of World War I, Gallipoli and the Anzacs, triggered by Peter Weir’s seminal Gallipoli (1981). It was based on new historical research that had stripped war of its militaristic, imperialist, and racial underpinnings to a story that the Anzacs were victims of mass slaughter, echoing some of the protest movement’s tropes of the 1960s and 1970s.

Weir’s central character was an idealistic 18-year-old who at the climax is torn apart by Turkish gunfire. The message reinforced the “birth of a nation” notion that Australia, and New Zealand, had moved beyond their colonial status. “Gallipoli as a place was increasingly invoked as a national totem rather than a set of actual experiences; a feeling rather than an event.”

Author Maurice Shadbolt responded to the Australian embrace of Gallipoli with his play, Once on Chunk Bair (1982), which described events on a day, August 8, 1915, that was this country’s “cruellest, and finest, hour,” and in which New Zealanders had “lost their innocence”.

Shadbolt also wrote the script for Gallipoli: The New Zealand story, a TV series based on the diaries, letters, and memories of those involved. While much of this “voices from below” approach was missing from the final broadcast version, Shadbolt later turned them into a bestselling book.

Diverging treatment

The next major anniversary of Anzac Day – the 75th, in 1990 – showed a divergence of treatment between the Anzac nations. Australia went all out with Prime Minister Bob Hawke and 10,000 other Australians attending a televised spectacle beamed back home from Gallipoli.

Turkey was also fully involved, with its government keen to draw attention away from the Armenian genocide issue that was being raised at the time. New Zealand, preoccupied with the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Waitangi, sent Governor-General Sir Paul Reeves almost as an afterthought.

Both Anzac and Waitangi days had competed over the years for political and public support. Every February 6 was marred by protests and tensions between European settlers’ achievements and Māori grievances. Australia’s success with its Gallipoli75 Task Force provided a sharp contrast between an overseas war commemoration as an exercise in national unity and a racially divisive one on home ground.

Unknown warrior

The Labour government of Helen Clark got the message, backing moves to repatriate and bury an unknown warrior at revamped National War Memorial in Wellington after the Dominion Museum and the National Art Gallery were combined into Te Papa at a new waterfront location.

Clark’s dedication speech in 2004 emphasised the grief and healing in New Zealand’s varied experience of war. Light compares this unfavourably with Paul Keating’s oratory on the “moral lesson” of the Anzacs at Australia’s equivalent event in 1993.

The Labour government downgraded New Zealand’s defence capabilities in the first decade of this century but the Anzac nations moved closer together in their observances and joint military operations. After her public humiliation at Waitangi in 1998, Clark refused all future attendances, while boosting the Anzac connection, including a $30 million payout for Vietnam War veterans in 2009.

Māori TV stepped up with live telecasts piggybacking on Australia’s lavish staging of the now entrenched event at Gallipoli in 2004, ahead of the 90th anniversary. The broadcaster’s role in the 100th anniversary widened the coverage to include the impact on families and women, while the involvement of indigenous TV networks allowed them to invoke colonial violence toward their respective communities.

Pulling power

An exhibition, Gallipoli: The scale of our war, was staged at Te Papa, making up for the absence of war commemorations. Light reveals that military historian Christopher Pugsley fought Te Papa staff to reduce the Māori presence to its correct representation, again confirming Anzac’s greater pulling power over Waitangi.

The Anzac nations’ rivalry didn’t stop at the centenary. Australia again spent up large on the Sir John Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux in France, while New Zealand’s much more modest gesture was to buy the former mayoral house at the walled village of Le Quesnoy to commemorate Kiwi Anzacs liberating that town from the Germans on November 4, 1918.

Meanwhile, efforts are occasionally made to honour the dead in wars fought in the 19th century on New Zealand soil. The problem, as wasn’t the case with Gallipoli, is agreement on which battle to commemorate. Like the Waitangi Day tussles, that isn’t likely to be settled any time soon.

But Light leaves no doubt about where the Anzac story has travelled. “The Anzacs, once seen as imperial citizen-soldiers, are now understood as heroic victims of violence who gave their lives in sacrifice for democracy, freedom and friendship.”

Anzac Nations: The Legacy of Gallipoli in New Zealand and Australia 1965-2015, by Rowan Light (Otago University Press)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.