Cultural warrior returns to the fray

Book Review: Self-help guru Jordan Peterson is back with 12 more rules for life.

Book Review: Self-help guru Jordan Peterson is back with 12 more rules for life.

The French government, supported by its intellectual elite, recently opened a new front in the cultural wars, shorthand for the left-right clash among the chattering classes. The French objected to an “invasion” of American ideas into its universities.

The irony was that these ideas, described as critical theory in race, gender, colonialism and much else, arose from French postmodernism that flourished after World War II. It turned the Marxist class struggle into one of power exercised by a patriarchal, white supremacist system over its oppressed victims. These were collective rather than individual identities, displacing the need to take personal responsibility or blame.

France was not the only country to be invaded by radical ideas that have been weaponised by activist professors. New Zealand’s academic corridors have embraced critical theory across all of the humanities and social sciences, as well as law, health and environmental studies.

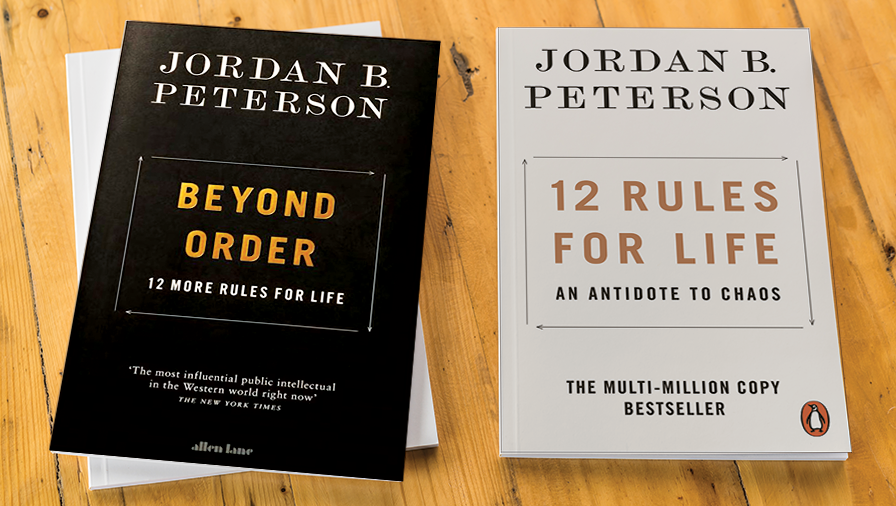

A veteran of this cultural war, Canadian clinical psychologist and self-help guru Jordan Peterson, has returned to the fray with a sequel to his bestseller, 12 Rules for Life: An antidote to chaos (2018). It sold five million copies in 50 languages, launching Peterson as a global intellectual with few peers.

This and one earlier book were backed up by You Tube videos, podcasts and public lectures in dozens of countries, including New Zealand in 2019. These appearances first became controversial in 2016, when Peterson attacked plans in Canada to introduce “gender identity and expression” as prohibited grounds of expression.

This resulted in campaigns for free speech against so-called “hate crimes” that continue today. While lionised in conservative circles as a critic of political correctness, Peterson instantly became a bogeyman for various forms of left-wing identity politics, including the cancel culture that has cost many their jobs.

Peterson himself faced hostility – an invitation for a visiting fellowship at Cambridge University was rescinded before he could take it up. He has been labelled an apologist for fascism in some publications, including the New York Review of Books.

Publisher’s staff protest

Peterson’s new book, Beyond Order: 12 more rules for life, created headlines even before its worldwide release in the past week. Editorial staff at the publisher, Penguin Random House, protested in both Toronto and New York, demanding it be withdrawn. Bookshops, including one in Wellington, indicated they would not stock it, as happened with 12 Rules for Life.

Commercial reality dictated that the publisher would not resile. Peterson is by far its most successful non-fiction writer. Billed as a sequel, with a black cover in contrast to the earlier book’s white cover, Beyond Order explores familiar themes from a different perspective.

The 12 Rules were a guide to bringing order out of chaos in people’s lives with common-sense advice on keeping to the straight and narrow in behaviour and decisions. The follow-up softens these traditional virtues with warnings about the dangers of too much structure.

Peterson likens this to a mix of conservatism with liberalism, though there is no backtracking in his exhortations. If anything, he has hardened up, partly due to personal events in his family over the past two years when he has been absent from the public eye.

It started in Zurich with his daughter Mikhaila undergoing the replacement of her artificial ankle. Two months later, his wife Tammy began a series of operations for kidney cancer, which later spread to her lymphatic system. This required two years of treatment in Toronto and Philadelphia.

Peterson himself became ill from anti-depressants prescribed after an autoimmune reaction to food he ate back in Christmas 2016. His withdrawal from benzodiazepines led to his admission to clinics in Moscow and Belgrade from January to May last year.

![[Jordan Peterson and daughter Mikhaila in Moscow’s Red Square after his treatment in 2020]](https://d2xgqyuql1olth.cloudfront.net/assets/Uploads/inline-images/Jordan%20and%20Mikhaila%20Peterson%20in%20Moscow%20-%20Instagram%20web.png)

All finally recovered, and Peterson has recast his book to include his extreme health experiences and belief that gains from pain are more valuable than intellectual abstraction.

He describes the mix of his new outlook on life as keeping one foot within order while stretching the other tentatively into the beyond.

“… we are driven to explore and find the deepest of meanings in standing on the frontier, secure enough to keep our fear under control but … constantly learning as we face what we have not yet made peace with or adapted to.”

Psychological advice

Peterson’s 12 rules are presented as psychological advice based on examples from his 30 years of clinical practice as well as research as a professor at the University of Toronto. He dwells heavily on ancient mythology and the Christian Bible as well as modern popular culture such as the Harry Potter series to underline how to pursue personal goals and learn from past wisdom.

Other dictums include the rewards of limiting your expectations, awareness of others’ views, when to stand up for principle and when to let go, and how to build successful partnerships.

Summed up like this, they resemble truisms preached by many religions and faiths to create the ideal civilisation. Some rules can be mundane, such as making one beautiful room in your house (Peterson is a collector of Soviet-era art). This echoes his earlier rule to clean your bedroom as a first step to bringing order into your life.

![[This image invoking Soviet art illustrates Rule VI “Abandon ideology” in Beyond Order]](https://d2xgqyuql1olth.cloudfront.net/assets/Uploads/inline-images/Peterson-soviet-poster.jpg)

Despite this banal-sounding advice, Peterson’s lengthy explanations are erudite and draw on stories that his audiences can easily absorb. He recounts that people often tell him he preaches and writes what they already know but cannot articulate themselves. This makes him a charlatan to some, particularly those who object to his underlying message.

He detests ideology, bringing him hard up against the fashion for ressentiment, a philosophical term used by Friedrich Nietzsche to describe blame for one’s failure. Peterson ascribes this to critical theory ideologists, who blame society’s shortcomings on the exercise of white male power and how it makes victims of those outside it.

For Peterson, fighting patriarchy, reducing oppression, promoting equality, transforming capitalism, saving the environment, and running every organisation like a business are ideological goals that are beyond the ability of any individual.

Isms aren’t solutions

The consequences of the totalitarian alternative, such as the hundreds of millions who died under communism or fascism in the 20th century, are reason enough to reject utopian ‘isms’ as a solution to any problem, he argues.

Instead, individuals themselves or as part of a group should address smaller, more precisely defined problems.

“We should conceptualise them at a scale at which we might begin to solve them, not by claiming others, but by trying to address them personally, while simultaneously taking responsibility for the outcome.”

He dismisses youthful zealotry for universal causes as a “false god” born of inexperience. He would prefer young people to deal with their own problems rather than follow the example of Greta Thunberg.

Similarly, he answers his feminist critics with statements that resemble those caricatured in the TV miniseries Mrs America on the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s.

“We lie to young women, in particular, about what they are most likely to want in life is taboo in our culture, with its incomprehensibly strange insistence that in the typical person’s life is to be found in career. But it is an uncommon woman … who would not perform what sacrifice necessary to bring a child into the world …”

Peterson’s defence of family values also requires a need to show gratitude no matter what life delivers. He praises the role, in the US and Canada, of Thanksgiving as a way of celebrating this with family and friends.

Gratitude should also be extended to society as the “beneficiary of tremendous effort on the part of those who predeceased us, and left this amazing framework of social structure, ritual, culture, art, technology, power, water, and sanitation so that our lives could better than theirs.”

In notes released by the publisher to acknowledge the global impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, Peterson advises patience as the pushback from vaccines allows for some restoration of normality.

“Be patient, as the concerns that plague you in the moment may well not be those that maintain their relevance for more than a comparatively short period of time. Sometimes the best strategy is merely to endure until the worst is passed by.”

Beyond Order: 12 more rules for life, by Jordan B. Peterson (Allen Lane/Penguin Random House)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.