An improbable scenario

The Avro Lancaster as a nuclear bomber?

The Avro Lancaster as a nuclear bomber?

Of the many tasks the ubiquitous Avro Lancaster carried out during its productive career, that of nuclear bomber was not one of them. In 1943, however, the Lancaster’s name appeared on a list of potential aircraft that could carry the United States’ first atomic bomb.

The Thin Man

At the end of July 1943, former naval officer Capt William S ‘Deak’ Parsons was appointed associate director of the team at Project Y at Los Alamos, New Mexico, the secret facility developing nuclear weapons led by physicist Dr J Robert Oppenheimer under the Manhattan Project.

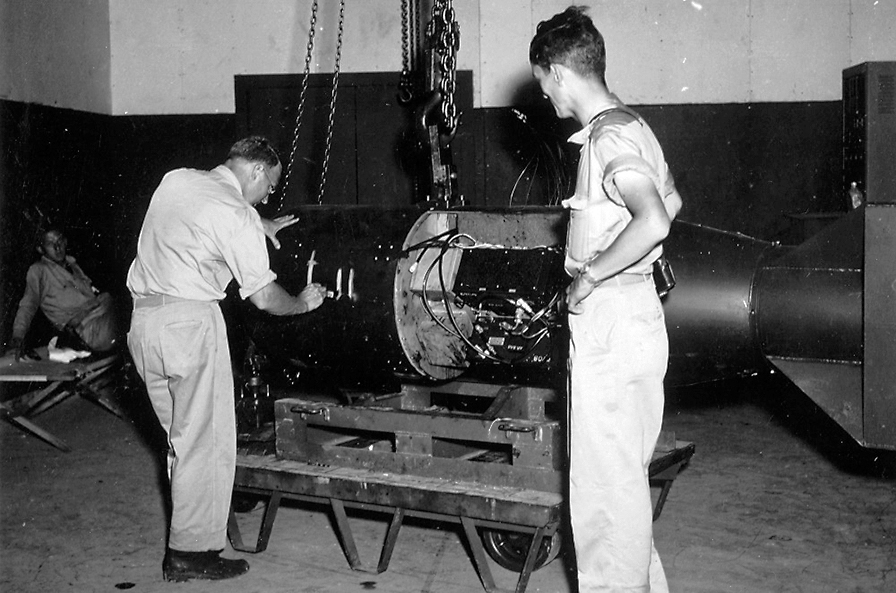

Parsons’ role was to design the mechanism for triggering the bomb, known as the plutonium gun. It was a device that activated its fissile material – material that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction – by firing it at high velocity at a segment of this sub-critical element to create a supercritical mass, triggering the chain reaction necessary for a nuclear detonation.

Inside the bomb casing, a conventional explosive fired a hollow projectile inside a gun barrel at a target piece at its opposite end. It was a crudely simple method of creating the required chain reaction, but in practice it worked. Only plutonium of the purest isotope (the by-product of the decay of a nuclear element – plutonium does not exist naturally as an independent substance but is found as a trace element in uranium) is required. Otherwise, impurities could reduce the effectiveness of the detonation.

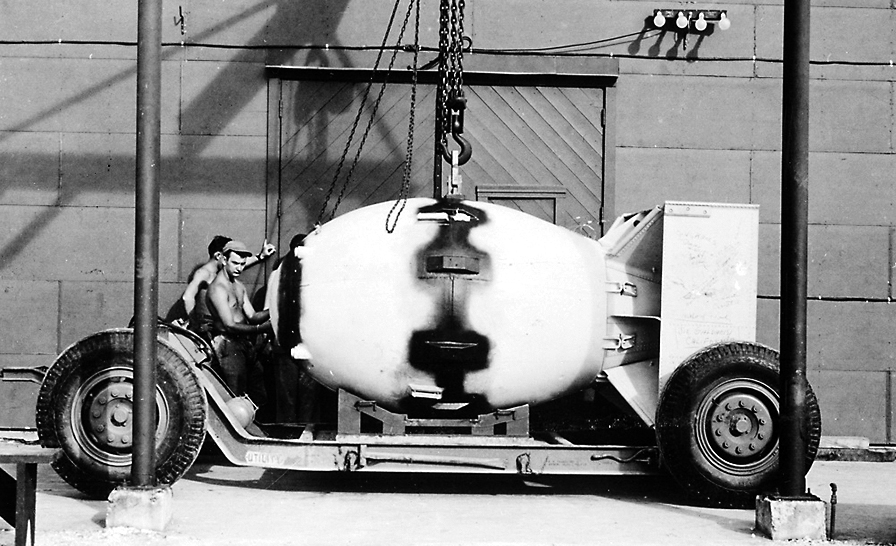

Parsons’ first plutonium-gun bomb was an inelegant device. At 17ft (5.18m), the gun length calculated by the resultant velocity at which the fissile bullet would travel to its target at a rate of at least 3000ft/sec, it had to weigh no more than a ton. As an ex-navy ballistics man, Parsons was able to corral his navy contacts in gun design to manufacture the barrel. The resulting weapon resembled a large rocket projectile with a simple cruciform tail and a bulbous head and was nicknamed Thin Man.

Its name and that of Fat Man, the contrasting implosion-type weapon being designed as a backup to the gun-type bomb, earned their names from Robert Serber, a former student of Oppenheimer. Thin Man came from the Robert Dalshiell detective novel of the same name and Fat Man was the name of Sydney Greenstreet’s character in the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon. The name Little Boy, given to the device dropped on Hiroshima, was simply a contrast to Thin Man.

On August 13, through Parsons’ connections, ballistics trials were carried out using a small-scale mock-up of Thin Man at the Naval Proving Ground, Dahlgren, Virginia. Dropped by a Grumman TBF Avenger, this was the first testing of a potential nuclear bomb shape.

Unfortunately for those concerned, the initial trial was a failure. Comprising a section of 14in piping mated to a 500lb bomb, the dummy device was nicknamed The Sewer Pipe Bomb by naval personnel. When dropped from the Avenger, it fell into a flat spin, a characteristic not witnessed before by ballistics experts.

Nevertheless, since the gun-type weapon was the preferred choice of a nuclear device, full-scale airdrops were requested. In charge of investigating a delivery system for these first-generation nuclear weapons was physicist Dr Norman Ramsay, working for Parsons in developing Thin Man, who set to work examining existing big bomber types for their suitability.

Using Thin Man’s 17ft length as a gauge, Ramsay’s report concluded that: “It was apparent that the [Boeing] B-29 [Superfortress] was the only United States aircraft in which such a bomb could be conveniently carried internally, and even then, this plane would require considerable modification so that the bomb could extend into both front and rear bomb bays.”

Comprising two 3.65m openings, the B-29’s weapon storage space was large but was broken in continuity by its wing centre section. Ramsay added: “Except for the British Lancaster, all other aircraft would require such a bomb to be carried externally.”

The unAmerican option

At the time Ramsay prepared his report, the highly advanced B-29 was experiencing difficulties. The biggest and most ambitious US aircraft development programme to date, it comprised thousands of independently manufactured components to be shipped to four separate assembly plants. Changes instigated by its designers and the operator, the USAAF, necessitated almost daily interruptions to the production schedules, to the extent that improvised USAAF modification depots were established to incorporate changes to aircraft rolling off the production lines.

By the end of 1943, although 100 aircraft had been delivered, only 15 of those were considered service worthy.

Its Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone engines frequently overheated, necessitating in-service limitations to operating procedures, a problem not fully cured until the removal of the Cyclone and its substitution with the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major in the B-29D programme, which resulted in the postwar B-50 Superfortress. As a result, tragedy struck the programme early; on February 18, 1943, the second prototype suffered an engine fire and crashed, killing all aboard and 21 people on the ground.

By late autumn 1943, Thin Man’s ballistic characteristics had been refined by increasing the size of the cruciform-stabilising fins and improving weight distribution. Having proved its impressive load-lifting capabilities for more than a year in active service, the Lancaster was a very real possibility for carrying Thin Man in its capacious bomb bay. Completely uninterrupted, at 10.05m it was unmatched in any existing heavy bomber and owed its size to a requirement in the Avro Manchester, the Lancaster’s ill-fated predecessor’s specification P.13/36, that it be able to carry two torpedoes internally.

The Lancaster Mk I’s maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 61,500lb (27,896kg) was progressively increased throughout the type’s career by the internal strengthening of its wing spars, more powerful engines, and paddle blade propellers. By February 1944, the Lancaster’s MTOW had increased to 65,000lb (29,484kg), with a further increase to 68,000lb (30,845kg) by March 1945.

These weights applied to conventional service examples only; the heaviest MTOW recorded by the type was for the Lancaster B.I (Special), modified to carry the 22,000lb Grand Slam earthquake bomb at 72,000lb (32,659kg).

Fortuitously, in October 1943, Lancaster designer Roy Chadwick was in Canada overseeing the licensed construction of the type by the National Steel Car Company, later renamed Victory Aircraft, at Malton, Ontario. Ramsay went to meet him there and, during their meeting, he produced illustrations of bomb casings of both kinds, gun-type and implosion-type. Without revealing their unique nature, he asked whether a Lancaster could potentially carry them.

Chadwick, somewhat intrigued, didn’t ask either but assured Ramsay that it could.

Armed with Chadwick’s assurances, Ramsay returned to Los Alamos and briefed Parsons on the suitability of the Lancaster as a Thin Man carrier. At this stage, however, the USAAF had not been included in Manhattan Project discussions, but Manhattan’s commander-in-chief Maj Gen Leslie Groves soon approached his equivalent within the USAAF, Gen Henry H ‘Hap’ Arnold. Groves was assured of USAAF support, under the proviso that the air force provided the delivery platform and its crew. When the possibility of the Lancaster was put to them, both men rejected it, insisting on the only American option – the B-29.

The fate of the Lancaster as a nuclear bomb carrier was sealed; despite Ramsay’s evidence, the troublesome B-29 was going to become the world’s first nuclear bomber. On November 30, the 58th B-29 off the production line at Boeing-Wichita, AAF serial no 42-6259, was flown to Smoky Hill AAB at Salina, Kansas, and then to Wright Field, Ohio, for modifications to its fuselage to enable it to carry Thin Man internally.

In March 1944 at Muroc Field, renamed Edwards Air Force Base in 1949, dropping trials with Thin Man and the bulbous Fat Man ballistic shapes, nicknamed Pumpkin Bombs, were conducted, with the former proving satisfactory because of the work done by the navy at Dahlgren.

During a subsequent drop, however, the bomb released itself prematurely within the B-29, damaging its bomb bay doors. This was blamed on the bomb shackles failing, leading to the logical solution of a single rather than multiple attachment points. For this, the USAAF turned to the Avro bomber, and the same Type F shackle designed to suspend the 12,000lb Tall Boy earthquake bomb was used to carry America’s first nuclear weapons aloft.

A possible past?

While awaiting plutonium for the construction of the first live Thin Man bomb, research continued into the efficiency of existing nuclear technologies and, in the spring of 1944, a breakthrough of sorts was made. Plutonium produced at the Hanford site at Benton, Washington, was riddled with impurities owing to its manufacturing process, which it was theorised could lead to reduced efficiency during firing or, at worst, a failure to ignite a chain reaction at all.

As an alternative, uranium isotope U-235 as a potential ‘bullet’ within the gun was proposed. Although U-235 was less efficient during the fission process than plutonium, this was considered an advantage as a lower velocity of 1000ft/sec needed to be achieved during firing.

This had an immediate impact on the entire programme. Thin Man was effectively terminated, as the gun no longer needed to be 17ft in length but could be reduced to less than 10ft and thus fit into a shorter casing. Little Boy was born.

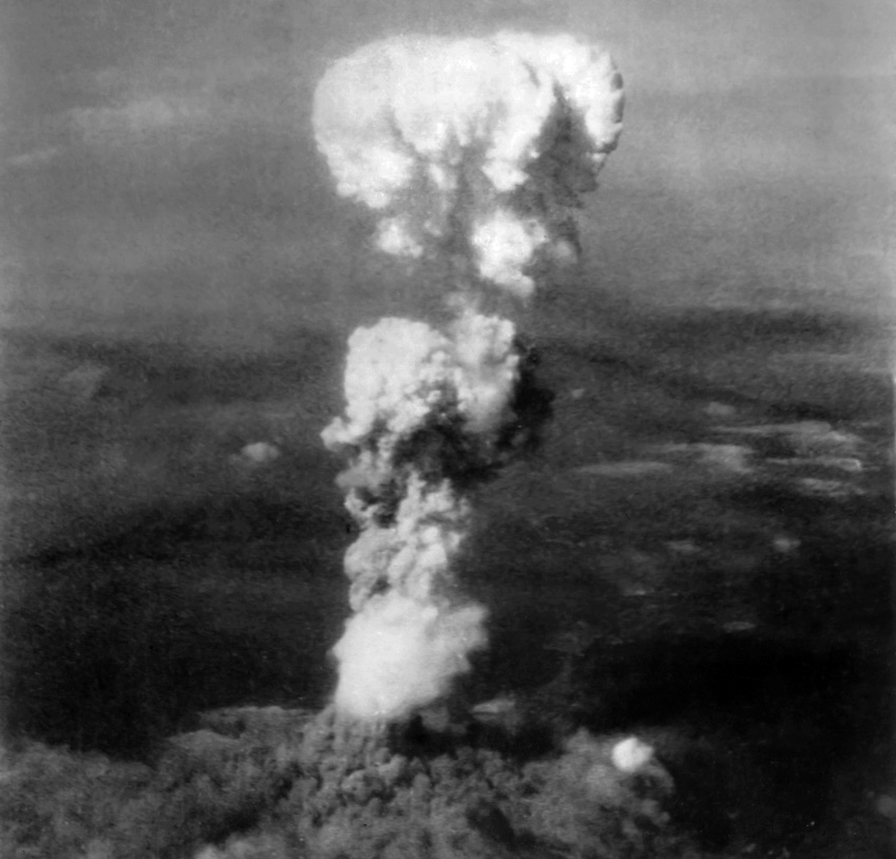

The rest, as they say, is history. Little Boy could fit unobstructed inside a single section of the B-29’s bomb bay with two inches to spare. On August 6, 1945 – dropped from B-29-45-MO 44-86292, named Enola Gay by its pilot, Col Paul W Tibbets Jr, with Deak Parsons as mission commander and weaponeer – Little Boy exploded over the Japanese city of Hiroshima, changing the world forever.

It is worth, at this juncture, pondering over what might have been. Had Ramsay got his way and the Lancaster been selected as the first nuclear bomber, could it have carried out that historic operation?

Let’s look at the Lancaster as a potential nuclear bomber by examining in detail what would be asked of it.

Bomb load

Little Boy was 3.04m long and 71.12cm wide, weighing approximately 4399kg. Fitting it inside the Lancaster’s cavernous bomb bay could easily have been done as it weighed less and was of a smaller diameter than Tall Boy, with its 96.5cm diameter, which could be carried internally if the Lancaster was fitted with bulged bomb bay doors.

Performance-wise, carrying such a load would have naturally reduced the bomber’s speed and height to achieve a useful range. No data survives from trials of Tall Boy-carrying Lancasters within the archives from the Aircraft & Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Boscombe Down but, on April 17, 1943, Lancaster ED825/G with no mid-upper turret and a bomb bay modified for the carriage of the cylindrical ‘Upkeep’ anti-dam mine arrived at Boscombe for testing.

At a MTOW of 63,000lb, the aircraft carrying 1774imp gal of fuel and a bomb load of 11,500lb, its range was 1720 miles (2768km) and its maximum speed was reduced to 256mph at an altitude of 11,000ft, from the 287mph of a standard Lancaster Mk I. The fitting of four Merlin 24s in place of Merlin XXs gave an extra 330hp (25%) and +18lb/sq in boost at takeoff.

In April 1945, Lancaster B.I (Special) PB955 was evaluated, and its specific air range was calculated with a Grand Slam fitted. The subsequent A&AEE766 report contains the following: “The results of the specific air range determination, corrected to ICAN standard conditions and to the mean weight of test to 64,000lbs … At this weight, the optimum specific air range under ICAN atmospheric conditions at 15,000ft in FS [fully supercharged] supercharger gear is 0.99 air miles per gallon [AMPG]. This is obtained by using full throttle and adjusting the RPM to give an ASI of 175mph. A speed increase to 190mph causes a 3% loss in range.”

A chart on the report shows a consumption figure of 0.96 AMPG for PB995 and 0.99 AMPG for similarly configured Lancaster PB592, both at a weight of 68,500lb. At 1774 gal (fuel load for a B.I (Special) carrying the Upkeep mine) at a weight of 64,000lb and an AMPG of 0.99, its range is 1756.26 miles. At the same fuel load at a weight of 68,500lb and an AMPG of 0.96, its range is 1703 miles.

These figures give an idea of what a Lancaster nuclear bomber’s performance might have been, and it doesn’t look very impressive. Carrying a maximum load, in this scenario with extra fuel compensating for a decrease from a 22,000lb to a 9700lb warload, the aircraft would be flying at a cruising speed of 175mph at an altitude of 15,000ft to achieve maximum range.

To put this into perspective, three years earlier, the Short Stirling, hampered by a poor ceiling, was being shot out of the sky over Germany at this speed and height.

Japan or bust

At the Quebec Conference held in September 1944, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill promised RAF Bomber Command support to the US effort to defeat Japan once Germany had been defeated. This scheme, initially comprising some 40 squadrons of long-range bombers, of which 20 would be capable of in-flight refuelling (IFR), was named Tiger Force.

Much preparation was undertaken to achieve its goals, which by late 1945 had shrunk in number considerably, although its equipment, comprising Avro Lincolns, Lancasters, and Consolidated Liberators as IFR tankers, remained the same. By the time Japan officially surrendered in September 1945, however, not one in-service RAF aircraft was capable of IFR; Tiger Force was counting on an early 1946 commencement date.

Avro, however, had proposed an extra-long-range Lancaster variant fitted with a 1200imp gal saddle tank, extending aft from the forward cockpit to a point just forward of the mid-upper turret’s location, which was removed, and Merlin 24s installed.

In May 1945, the first Lancaster so configured, Mk I HK541, flew to India to investigate the feasibility of operating in high temperatures at a MTOW of 72,000lb. Trials were encouraging; with a full fuel load of 3154gal, a range of 3470 miles was achieved carrying a war load of 6000lb. The crew spent some 18 hours in flight.

Despite this enormous boost to the Lancaster’s performance, it was decided that IFR offered the best solution for future operations.

Raid statistics

Let’s now examine Enola Gay’s Hiroshima raid statistics for comparison. At 2am on August 6, 1945, Enola Gay departed Tinian Island to drop Little Boy on Hiroshima, returning at 2.58pm after a journey time of 12hr 58min on an approximate round trip of 2722 miles. Using these figures, Enola Gay’s calculated average speed was around 216mph. Loaded with the 9700lb bomb and fuel for its mammoth round trip, Enola Gay’s gross weight was 140,000lb. Little Boy was dropped from an altitude of 31,060ft.

These figures illustrate the scale of such a task ahead of the crew of a Lancaster nuclear bomber. On top of performance unattainable by a modified Lancaster Mk I (Special), Enola Gay offered a fully pressurised shirtsleeve environment aboard, whereas the Lancaster was unpressurised, necessitating the discomfort of the crew breathing oxygen throughout the flight.

Only with IFR could a Lancaster achieve the range required to fly from Tinian to Hiroshima and return – and, even then, its maximum altitude would have been only half that of the B-29’s, at a lower average speed. Since IFR had not become a reality in the wartime RAF, the Lancaster simply could not have done it.

Tiger Force was intended to operate from Okinawa, which was captured from the Japanese in April 1945 and was used as a staging and diversionary landing field for B-29 raids against the Japanese homeland.

If the Lancaster nuclear bomber was to operate from Okinawa, that would bring Hiroshima within range, with a round trip of approximately 1262 miles. The downside to Okinawa was its proximity to the Japanese home islands; despite being captured in April, Japanese attacks against it did not cease until the war’s end, which would have been a risky proposition for the basing of such an important operation.

Another consideration was that Little Boy was a one-off – the production nuclear bomb and the very first device to be detonated, at the Trinity test site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, was an implosion-type bomb. Fat Man was to become the standard US nuclear weapon and the Lancaster could not accommodate its 1.52m diameter internally, not without removing its bomb bay doors, as was necessary when carrying Grand Slam. Flying to Nagasaki carrying a Fat Man was out of the question, owing to the impact on the aircraft’s performance with such a large device suspended below it.

From whichever angle the Lancaster as a nuclear bomber is examined, along the traditional timeline of raids against Japan in August 1945, the result is a highly improbable scenario. The Lancaster was just not capable of carrying it out.

Could the Avro Lincoln with its improved performance have done any better? Marginally, but timeline-wise it was still not possible.

The first Lincolns entered service with Bomber Command mere days before the Hiroshima raid – in early August 1945, three of the new bombers arrived at RAF East Kirkby, Lincolnshire, to join 57 Squadron. This was hardly a fit for such a specialised operation.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.