Contradictions of an intellectual in business

OPINION Book Review: Biographer tackles the enigmatic billionaire Peter Thiel.

OPINION Book Review: Biographer tackles the enigmatic billionaire Peter Thiel.

The privately-owned Stanford University in California is one of the two best in the world, beaten only by Oxford, England in the Times Higher Education rankings.

Founded in 1885 by railway tycoon Leland Stanford, its alumni have created companies whose revenues and jobs created are equivalent to the world’s seventh-largest economy.

Companies created on or near the sprawling campus in Palo Alto include HP, Cisco, Google, Yahoo!, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Snapchat.

Stanford’s invention of the semiconductor gave rise to Silicon Valley and eventually the internet. The university has produced 85 Nobel laureates and is home to the Hoover Institution, a leading conservative think tank.

Yet, despite these impressive pro-business credentials, Stanford is no hotbed of conservatism. In fact, its student body vetoed the Ronald Reagan library, a repository created for every American president.

Conservative pushback

In 1987, a ‘rainbow’ march on campus prompted a response from a group of libertarian conservative students, leading to the establishment of the Stanford Review, which defended ‘traditional Western’ values against the emerging ‘cancel culture’. A co-founder was Peter Thiel, born in Germany but mainly brought up in America by his immigrant parents.

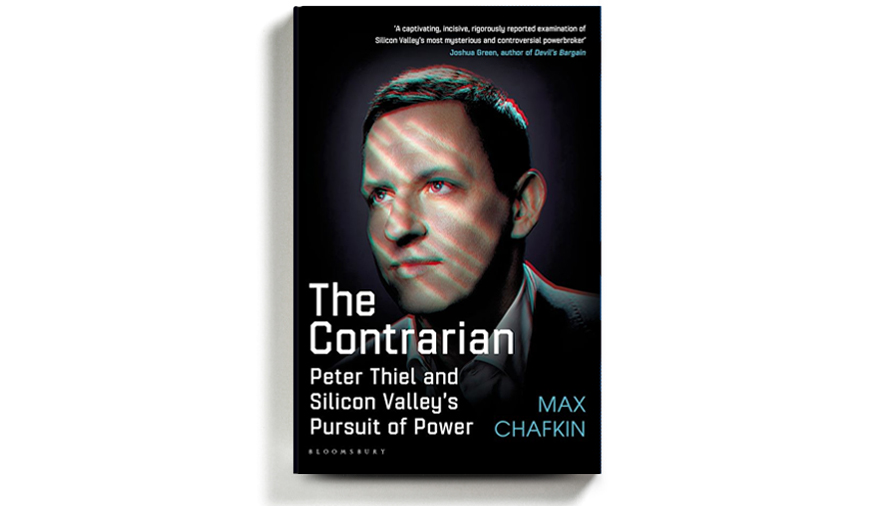

Both incidents are recorded in The Contrarian, a biography of Thiel by Bloomberg Businessweek journalist Max Chafkin, who has reported on Silicon Valley affairs for 15 years.

The university burnished its progressive reputation last month when it presented the annual US$100,000 Stanford Bright Award, its top environmental prize, to New Zealand climate change activist India Logan-Riley. She made headlines around the world at COP26 in Glasgow – her third appearance at the UN forum – by blaming climate change on British “invading forces” who 250 years ago “arrived at my ancestors’ territories, heralding an age of violence, murder and destruction …” She continued: “Land in my region was stolen in order to extract oil and suck the land of its nutrients while seeking to displace people.”

The Stanford award was donated by a law graduate, Ray Bright, whose generosity may well be felt here in New Zealand.

Different spin

Chafkin puts a much different spin on Stanford’s link to New Zealand via Thiel, another law graduate. As is well-known, Thiel became a New Zealand citizen during the Key government through the immigrant investment scheme. But it would appear, though this occurred at a time when talk of Silicon Valley ‘preppers’ seeking boltholes in Central Otago was common, Thiel did little to follow through on what Chafkin calls a “back up”.

Thiel has since sold his Queenstown residence – one of many around the world – but has plans to build on his larger property at Lake Wanaka. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Thiel chose to observe the final stages of Donald Trump’s administration from his Hawaiian hideaway.

While much of Thiel’s public life is well documented, making him a key target for journalists and others, ranging from the mainstream to the conspiracist, Chafkin is more intent on understanding Thiel as a person.

The biography’s title emphasises his contrarian positions on many issues but a more apt description would be his contradictions. At Stanford, Thiel was influenced by René Girard, the French Christian philosopher who argued that people are motivated by a desire to imitate each other. This leads to envy and violence in the form of ‘scapegoating’ innocent individuals, such as Jesus or Joan of Arc, to channel and control these feelings.

Girard showed Thiel, a geeky chess player and social outsider, how being a Christian conservative could be “an act of defiance against the campus culture he was coming to despise,” as Chafkin puts it.

False image

Chafkin lists other contradictions of how Thiel has used networking and storytelling to construct a false image of his real nature. Yes, he has created companies that have defined the culture and economy, made billions of dollars of wealth for himself and many others, and provided hundreds of thousands with a job. “He has been the rare futurist who actually managed to accelerate the future,” Chafkin says.

But, on the downside, Thiel has contributed to making America more reactionary and worse off. “He is a critic of big tech who has done more to increase the dominance of big tech than perhaps any living person,” Chafkin writes. “He is a self-proclaimed privacy advocate who founded one of the world’s largest surveillance companies [Palantir Technologies].” A champion of free speech who was also responsible for taking down a media outlet – the online gossip website Gawker, which had outed his gayness.

All of these negatives, and some of the positives, are presented in detail through a mix of sourced and anonymous comments. An example is Thiel’s relationship with Tesla founder Elon Musk, now America’s richest man (on paper).

Chafkin recounts how when they merged their non-bank payments ventures, PayPal and X, Musk wrote off his McLaren supercar in a crash while Thiel was a passenger. Thiel considers Musk as reckless while Musk thinks Thiel is only into tech to make a profit.

Years later, Musk tells Chafkin: “Peter likes the gamesmanship of investing – like we’re all playing chess … I am fundamentally into doing engineering and design.” Chafkin then quotes an anonymous source for a more succinct summary: “Musk thinks Peter is a sociopath, and Peter thinks Musk is a fraud and a braggart.”

Thiel sold PayPal to eBay, its major client, for a whopping $US1.5 billion, after he engineered the deal up from US$1.2b. The sale wasn’t popular with everyone in the so-called PayPal Mafia, but they all went on to greater financial success.

Hedge funds

Thiel reneged on staying at eBay and started his own hedge funds, which have been highly successful. He turned down an investment in Tesla, this week worth a huge US$1 trillion, saying electric cars didn’t interest him. But he did like Musk’s SpaceX venture.

Thiel also backed Facebook, as depicted in The Social Network, which is not sympathetic to the Machiavellian moneyman. Thiel sold out of Facebook after it went public, at US$20 a share (they are now worth US$328), but remained on the board and is still close to founder Mark Zuckerberg.

Chafkin recounts the ever-sceptical Thiel as telling its staff, who are under constant political pressure from all quarters: “My generation was promised colonies on the moon. Instead we got Facebook.” He believes technology in the US has stagnated because of the obsession with racial, ethnic, and gender identities.

Much of this dislike is aimed at Google, the biggest of the Stanford startups, and its monopolistic practices and its onetime wooing of China. In one twist, Chafkin reveals Thiel used his influence with President Trump to pardon a Google engineer who had been jailed for 18 months on charges of stealing intellectual property.

As you might expect, Thiel does not emerge well from this portrait, in which his contradictions are those of a calculating fraudster. Chafkin refers to Thiel moving in circles with the likes of heavyweight conservative intellectuals such as Niall Ferguson and Jordan Peterson, but rather than elaborate on these associations, he prefers to tie Thiel to the alt-right.

Similarly, Chafkin initially dismisses Palantir’s data analytic software as vaperware despite it remaining a major supplier to US defence and intelligence agencies. Thiel’s successful use of the law against governments – usually a recipe for disaster if you’re wanting contracts or avoiding taxes – under-rates his ability to apply his legal nous. David Parker’s wealth tax probe into New Zealand richlisters suggests they would be well advised, along with their lawyers, to be quick to read this book.

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power, by Max Chafkin (Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.