Germany’s spy state lives on

Book review: An FBI agent tackles legacy of world’s most pervasive secret service.

Book review: An FBI agent tackles legacy of world’s most pervasive secret service.

The world’s democracies are in retreat. But there’s always hope when popular protests break out in the corrupt dictatorships of Africa, Asia and Latin America, or in authoritarian socialist regimes such as Belarus, Nicaragua and Cuba.

Freedom House, a think tank that promotes democratic practices, reports that freedom across the globe has declined for 15 straight years. Last year, 18 countries suffered declines in democratic trends, while six improved.

Recent additions to this rollback range from Hungary in the European Union to Turkey, Hong Kong, and Myanmar. The most successful at quelling dissent are military-backed regimes and those devoted to totalitarian ideologies, of which the standouts are China, Russia, Iran and Venezuela.

Three decades ago, it was a different story, as the Soviet Union collapsed, giving a dozen or more nations their chance for freedom. For the most part, these transitions were remarkably peaceful, particularly in eastern Europe. In central Asia, the former Soviet rulers merely changed their labels and slogans, carrying on with business as usual.

In all but one example, these countries asserted their newly-found independence. The exception was the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which was absorbed into the German Federal Republic after 40 years under the control of the Socialist Unity Party, better known as the SED.

The SED was led by German communists who had spent World War II in Moscow. They could count on the occupying Red Army to suppress any dissent or demands for Western-style democracy.

One of those communists was Erich Mielke, an admirer of the Bolsheviks’ Cheka secret police established during the Russian Revolution in 1917. The Cheka was the predecessor of the NKVD and the KGB.

Failed uprising

In 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, an uprising by east German workers threatened the new GDR state. Four years later, Mielke took charge of the Ministry for State Security, or Stasi for short, and built it into world’s most pervasive secret service. Like its Russian big brother, the Stasi had an international arm, the HVA, but its main purpose was to spy on the GDR’s 16 million citizens.

Its functions went beyond internal surveillance and foreign espionage to include the roles of the police and judiciary. It opened mail, monitored telephone calls, issued travel permits, and scrutinised applicants for government and university posts.

It later emerged the Stasi also controlled dozens of businesses, including construction, electronics, military weapons trading and smuggling, as well as operating a bus service and running the national sports organisation.

By 1953, the Stasi already had more officers than Hitler’s Gestapo and, at its abolition in 1989, had nearly 100,000 full-time staff. In addition, it had some 190,000 active informers, known as IMs, meaning every 63rd citizen had a Stasi connection. They operated from 209 offices throughout the GDR, which was a third bigger in area than New Zealand.

During its existence, the Stasi employed some 250,000 full-timers, had 600,000 informants, and imprisoned some 280,000 citizens. It held files on six million individuals. Many were interrogated, typically using techniques such as sleep deprivation.

Punishment lacking

Yet, after the agency was dismantled, only 182 officers were charged and 87 convicted of Stasi-related crimes. Just one was jailed. Mielke, who held the top post until the end, served a two-year sentence but not for a Stasi crime. This was not the fate of many Gestapo officers, who faced trial for war crimes and were severely punished.

The free ride for the Stasi created a substantial lobby of past members who are still active in German life and politics. They are the subject of The Grey Men, by former FBI agent Ralph Hope who, among many positions, was deputy head of the agency’s Baltic States office.

Hope’s book follows that of Australian writer Anna Funder, whose Stasiland was published in 2002 and remains one of the best-known books in English of first-hand accounts by Stasi officers and their victims.

Coincidentally – because Hope does not list Funder in his bibliography – both books start with events that triggered the effective collapse of the GDR on November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall was breached.

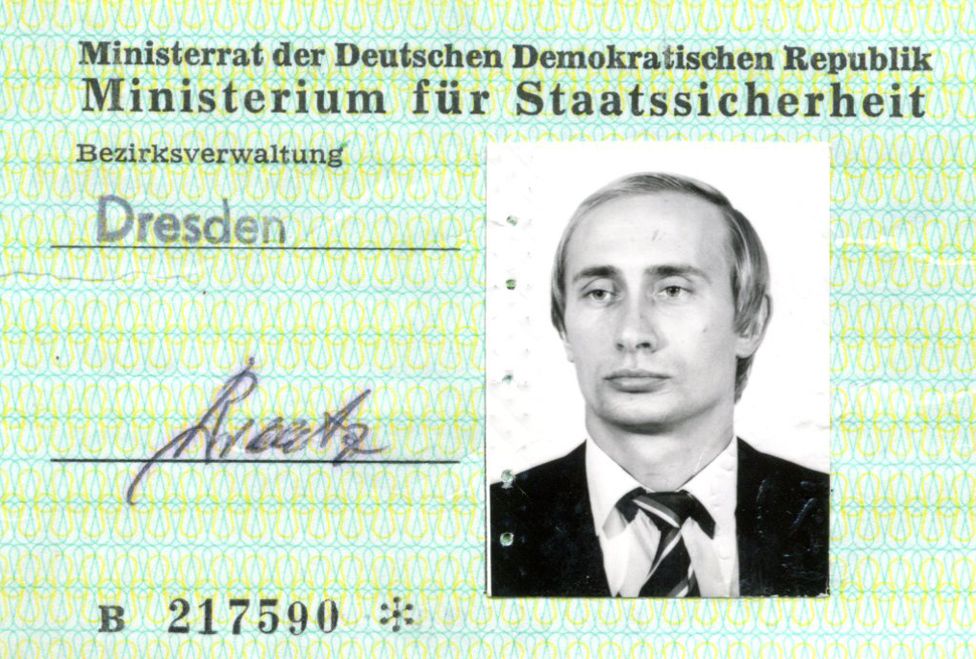

Funder chose the peaceful occupation of the Ruden Ecke, headquarters of the Stasi in Leipzig, as citizens sought to prevent the destruction of files. Stasi officers had fled, fearing their fate would resemble that of the Gestapo. Hope opts for Dresden, with the added drama of the intruders being turned away at gunpoint from the KGB’s office, then headed by Stasi-card carrying Vladimir Putin. Both authors note the shock of occupiers finding thousands of glass jars containing items of clothing that identified the “scent” of suspect citizens.

Standing joke

While the GDR’s sudden collapse was a surprise to both Eastern and Western intelligence agencies, it was not unexpected. Funder recalls a standing joke in Stasi circles about why the Titanic should be raised: the Americans wanted the jewels, the Russians the technology, and the East Germans the band that was playing as it went down.

After Mikhail Gorbachev loosened the reins of Communist Party power in the Soviet Union, all of the eastern bloc satellites were in revolt. It was obvious Moscow would not help the SED.

Yet Meilke had a plan to foil any widespread uprising. Operation Day X would round up 86,000 suspects and put them in already arranged detention centres. But the order was never given and the Stasi did not fire a shot.

Both books are built around personal case studies but Hope has a wider agenda. He wants to know what happened to the SED’s US$11 billion in hard currency that has not been traced. He suspects some of it has been used to continue the influence of ex-Stasi officers.

The SED was renamed as the Party of Democratic Socialists and later became part of Die Linke, Germany’s most left-wing political organisation. Its main cause continues to be the global anti-fascist (antifa) movement, a term first coined in Moscow in 1923.

Criminal state

Among its many crimes, the GDR earned hard currency by ransoming political prisoners to the Federal government; selling its own citizens’ blood donations to foreign health services, which was lucrative during the height of the HIV Aids epidemic; and engaging in large-scale trading of illegal weapons, drugs and migrants seeking entry to the European Union.

Hope describes the difficulties still faced by advocates for Stasi victims and those who wish to curate its history. One of them, Hubertus Knabe, headed a campaign to turn the Stasi’s Berlin headquarters from a museum into a living memorial but he was later removed as director.

Hope blames this on the ex-Stasi establishment, many of whom kept their positions in the judiciary, educational institutions and other government agencies. Some were elected to the German parliament where they have supported ‘hate speech’ legislation that is aimed at curbing extreme right-wing groups such as neo-Nazis but not those who ran a repressive regime for 40 years.

Protected by privacy laws, former Stasi officers are running large businesses, such as the Nord Stream pipeline controlled by Russia and investment funds. Those who taught in Stasi-controlled faculties on how to commit murder and administer deadly poisons are still in their posts.

Germany’s oldest and most prestigious university, Humboldt, was one such institution. It lavished degrees on GDR sympathisers in the West, including a PhD for Angela Davis, a leader of the Black Panthers movement in the US.

Hope says even the highly-praised film about the Stasi, The Lives of Others, was tainted by ex-Stasi involvement. In return for expert advice on Stasi techniques, the surveillance officer in the drama prevented the arrest of his victim, something Hope says never occurred in real life.

While Hope often overstates his case, and repeats himself with inconsistent information, the whitewashing of the GDR is more real than imagined. Ostalgia is a neologism for the phenomenon of looking back at the GDR as a “funny and harmless” period in German history. This is in contrast to the Nazi period, which lasted for less than a third of that time.

Undoubtedly, the peaceful unification of East and West is a matter of pride for many Germans. This is confirmed by the rapid rise of Angela Merkel to be chancellor of united Germany in 2005 after entering politics for Democracy Awakening, a non-communist party. After the first (and last) free election in the GDR, she became deputy government spokesperson, and was present at the final formal media conference before this unlamented state officially ended on October 3, 1990.

The Grey Men: Pursuing the Stasi into the present, by Ralph Hope (Oneworld/Bloomsbury).

Stasiland, by Anna Funder (Text Publishing).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.