Solving the US dollar puzzle

OPINION: If inflation at home goes up, interest rates tend to go up and the currency comes down, causing currency volatility.

World currencies.

OPINION: If inflation at home goes up, interest rates tend to go up and the currency comes down, causing currency volatility.

World currencies.

After many years of relative stability, global currency volatility is back. Why now? Economics 101 tells us that there is a negative relationship between inflation and currencies. Inflation decreases the value of currency in purchasing goods, which drives down the currency’s worth relative to other currencies.

Irving Fisher.

In addition, the accepted response by reserve banks to rising inflation is to increase interest rates. However, the disparity between the exchange rate of two currencies should be equal to their countries’ interest rate differential, suggesting if interest rates go up in a country, its currency depreciates.

This is known as the International Fisher Effect, named after Irving Fisher, who is considered to be one of the greatest economists the US has ever produced.

So here you have it: if inflation at home goes up, interest rates tend to go up and the currency comes down causing currency volatility. It shows that inflation and interest rates dominate the fate of a country’s currency.

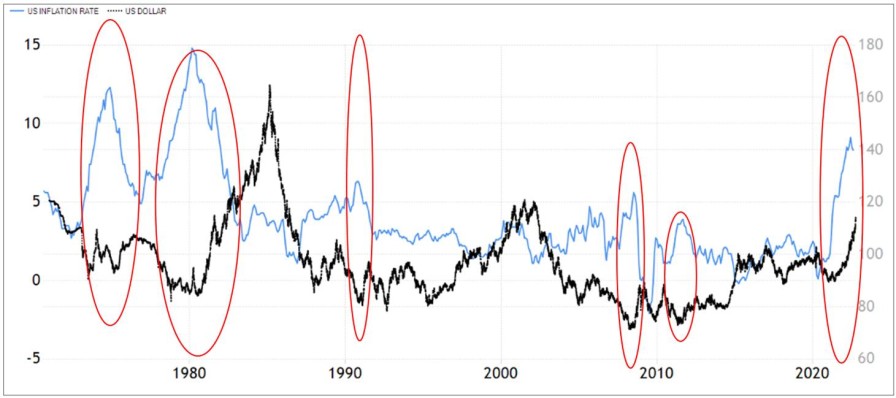

Let’s put the theory to the test by looking at the relationship between the US inflation rate and the value of the USD index, which tracks the relative value of the USD against a basket of important world currencies.

In the past 50 years, on every occasion US inflation exceeded 5%, the USD index was in its lowest quartile of value.

But what happens when every economy is experiencing higher than desired inflation? The focused reader would have noticed that over the past 12 months Fisher’s prediction doesn’t hold. The USD index has strengthened significantly against all other major traded currencies (including the NZD) despite a steep increase in US inflation (only the euro, British pound and Swedish krona have had inflation rates marginally higher than the US).

So, why is the USD currently a global juggernaut? Could it simply be because the best ‘risk-free’ interest rate return in the world happens to be in the world’s most vaunted ‘risk-free’ currency? Don’t forget that more than 60% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in USD and that President Nixon famously exported US inflation to the rest of the world in the 70s by creating the ‘petrodollar’ and dispensing with the gold standard. This put the USD solidly on the world stage as the go-to currency in times of risk uncertainty, be that economic or geopolitical (war).

Perhaps good old-fashioned greed is the prime motivator for the USD investment boom over the past 12 months. Note that US money markets have seen more than US$5 trillion invested in the past six weeks alone and why wouldn’t you buy two-year US treasury bonds yielding over 4% knowing you are guaranteed to get your investment capital back?

Then there are the globe’s fund managers, who have come off nearly 15 years of effortless ‘super’ returns for their investors from debt-leveraged assets that seemed to magically appreciate into the perpetual future. Beating a low inflation benchmark was easy.

These same managers are now having to work hard for their client returns beyond the usual morning coffee round chat (international coffee prices have also gone up by more than 100%, so these chats are briefer). They appear to be getting on board the USD super-tanker and buying up short-dated bonds for as long as the Federal Reserve keeps stoking the Fed funds interest-rate boiler room. With President Joe Biden looking to go on a fiscal spending spree, it looks like the supply of US treasury bonds will be there to feed the demand.

Where does this leave the NZD, given that much of the Kiwi’s perceived international value is determined by the mighty USD? New Zealand can also deliver a ‘risk-free’ return of more than 4%, with lower inflation than the US and considerably more hay in the fiscal haybarn, suggesting that the NZD fundamentals remain comparatively attractive.

If we can keep our inflation rate at or below our major trading partners, then our TWI should continue to hold up quite well, creating some currency stability.

The USD should have depreciated over the past 12 months given that it has completely over-stretched itself in the same way we have seen global assets overreach themselves over the past decade.

It hasn’t, which is puzzling.

It seems behavioural economics continues to rule: self-interested investors (as so clearly explained by Adam Smith in his famous book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations) taking on too much risk and underestimating likely losses, when chasing potential gains (Prospect Theory developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky).

The investment herd looks set to continue piling into more USD short-term bonds as the Fed continues to raise rates, especially while other central banks are caught like possums in the head lights.

The turning point may well be when US inflation shows clear signs of abating and the Fed readjusts its narrative.

This week’s US inflation update for September has not helped. Headline annual inflation marginally dropped to 8.2%, but the real howler was core inflation (ex-volatile food and energy) rising to 6.6% and this now at a 40-year high. It is looking more certain that the Fed will have to feed more into the hungry USD in coming months. Watch this space!

Christoph Schumacher is professor of innovation and economics at Massey University and director of the Knowledge Exchange Hub.

Stuart Henderson is an independent financial market risk adviser with more than 35 years’ experience, including as a partner at PwC.

This content was supplied free to NBR.