Nearly every central banker in the world is embarking on a tightrope journey, with the endgame being the successful containment and lowering of inflation back to policy target settings.

Falling off the tightrope can be dangerous for both the funambulist and the central banker; injury and loss of life for the former and causing severe damage to the economic fabric in the form of hyperinflation, currency depreciation, and long-term societal impairment to the latter.

Some central bankers have begun the journey with confident strides while others, such as the European Central Bank, remain nervously tentative. It is now all about timing, pace, and careful balance. To contain this global inflation pandemic, the central bankers of major economies are looking for a more coordinated response.

However, this is not straightforward. To ensure the tightrope has the correct tension, each central banker needs to be able to fine-tune their monetary actions to their respective country’s inflation idiosyncrasies.

Central bankers have different widths of a tightrope to balance on but universally have similar balance bars. These bars, however, appear to be weighted differently in terms of economic growth on one side and monetary policy medicine (interest rates) on the other.

This is challenging for our funambulist who has control over interest rates but not necessarily over economic growth. Increased government spending would stimulate growth but boost inflation. How would you feel if you were on a tightrope between two skyscrapers and the gradient of your rope suddenly increases?

The width of the tightrope is determined by the leverage of household and government debt to GDP. Household debt crudely measures the public ability to absorb painful monetary policy medicine, while government debt represents the fiscal capacity of the Government to provide an occasional lending hand to prevent our funambulist from falling (hay in the haybarn). The wider the tightrope, the easier it is to keep balance and the quicker the pace of the crossing.

What’s different?

Global economies have experienced inflation before, so what’s different this time? To answer this question, we need some historical context, so let’s journey back to the 1970s and 80s, when inflation was previously a sticky global problem requiring innovative thinking (it was also before the surge of independent central banks).

Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko, from Oliver Stone’s 1987 film Wall Street.

This was a time when there was comparatively plentiful fiscal hay in the respective haybarns and before globalisation taught the world that “debt is good” (apologies for misquoting Gordon Gekko, our fictional villain from Oliver Stone’s movie Wall Street or the non-fictional John Keynes).

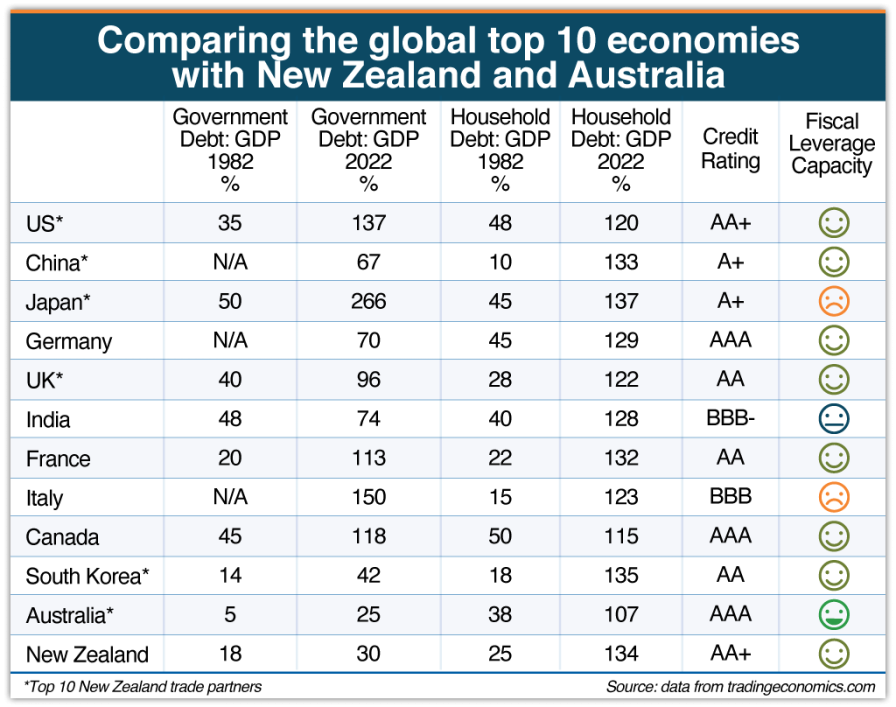

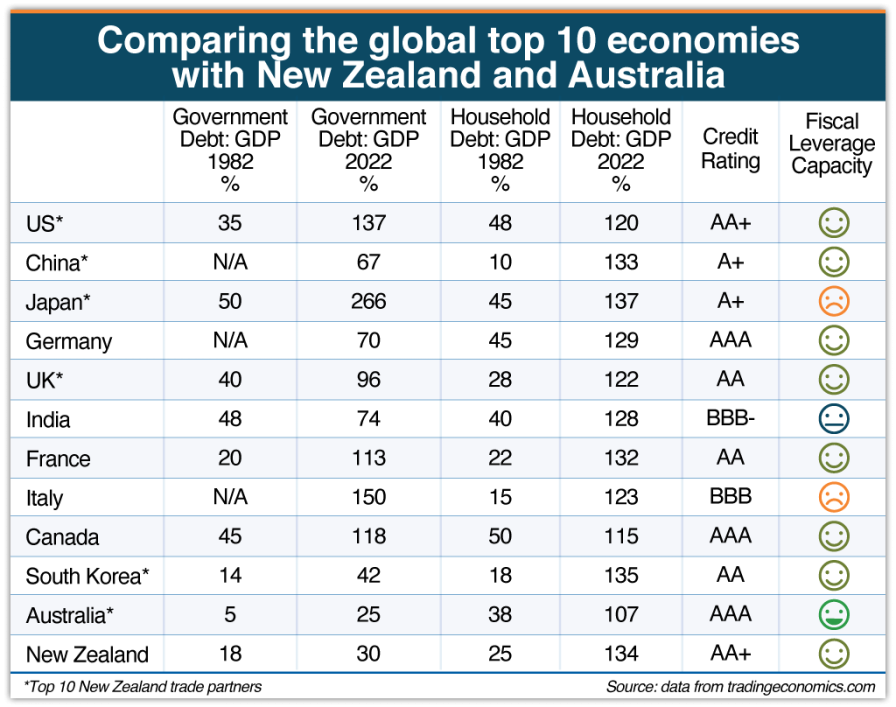

Over the past 40 years, we have witnessed a trending acceptance of increased debt leverage running alongside globalisation, with the premise that as long as GDP constantly grows, debt can be perpetual. I invite the reader to ponder the global perception of debt in the 1980s compared with today, using the following grid that compares the global top 10 economies with New Zealand and Australia.

With the hefty increase in debt, households are now under significant pressure as they have far less capacity to withstand the slings and arrows of outrageous monetary policy medicine, ie, higher mortgage rates, than in the 80s.

The US has the advantage of having a comparatively longer fixed-rate mortgage market (30 years) than New Zealand (five years), and the average fixed-rate term of New Zealand mortgages is currently less than two years.

This makes our household debt far more susceptible to rising interest rate impacts on sustainable household affordably.

Simply put, New Zealand households will get a far tougher and more bitter taste of monetary policy medicine through higher mortgage rates than the US. New Zealand’s household debt leverage capacity will not be supportive of our central bank’s monetary policy initiatives.

Wriggle room

New Zealand does, however, appear to have wriggle room for carefully orchestrated government fiscal assistance to sugar-coat the RBNZ’s inflation-busting interest rate medicine.

Economic purists will voice concern that increased government spending will only fuel inflation higher. However, for economies that have already utilised their household debt leverage capacity to the max, it surely falls on governments with plenty of fiscal hay in the haybarn to start feeding it out!

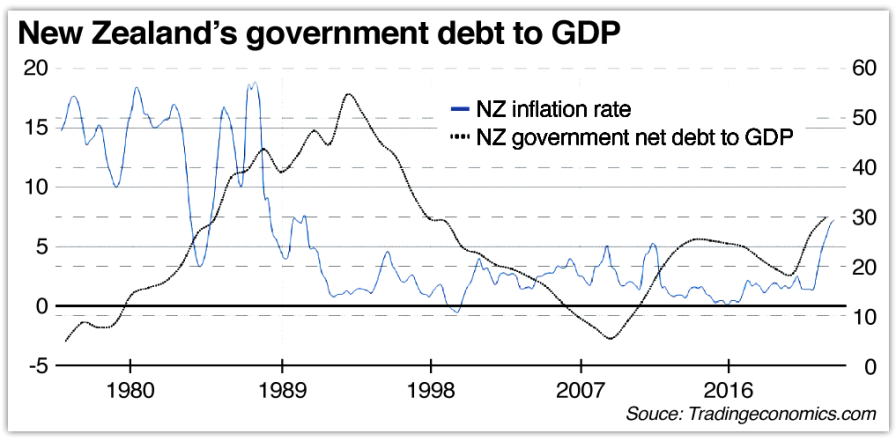

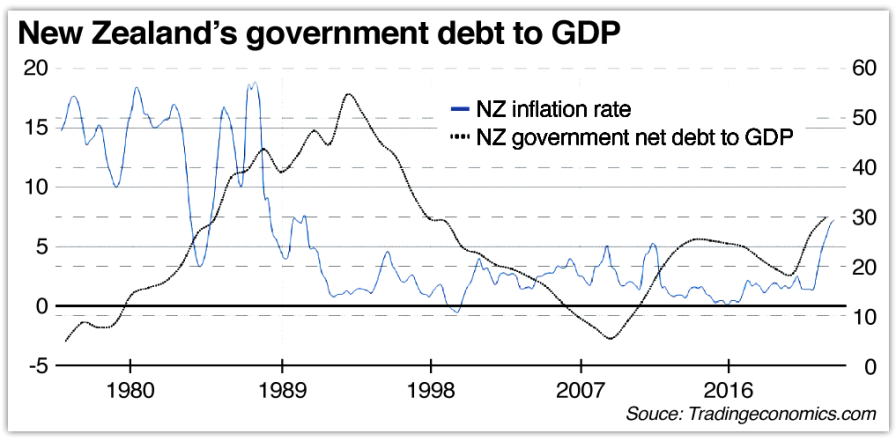

This wouldn’t be new for New Zealanders, as the following graph shows. Clearly, New Zealand’s government debt to GDP was leveraged to assist with the fighting of the 70s and 80s sticky inflation (the blue line is inflation and the black line is government debt to GDP). Government debt to GDP is a reasonable proxy for the tightrope’s bandwidth, but countries differ in their capacity to leverage this ratio (fiscal hay capacity). For example, the US has a greater leverage capacity than, say, a country whose underlying credit rating is significantly less than the US.

Government debt to GDP is a reasonable proxy for the tightrope’s bandwidth, but countries differ in their capacity to leverage this ratio (fiscal hay capacity). For example, the US has a greater leverage capacity than, say, a country whose underlying credit rating is significantly less than the US.

A crude assessment of the top 10 global economies, together with New Zealand and Australia, would indicate that only a handful can fiscally assist their respective central bankers.

The last time global inflation resembled the current inflation phenomenon, household debt was relatively unleveraged, so central banks got away with increasing mortgage rates to swindling heights to bust inflation.

The situation is very different now as our households are under significantly more pressure than 40 years ago.

The tightrope is very thin, which means our funambulists will need to balance their monetary policy actions more carefully or risk a nasty fall.

Christoph Schumacher is professor of innovation and economics at Massey University and director of the Auckland Knowledge Exchange Hub.

Stuart Henderson is an independent financial market risk adviser with more than 35 years’ experience, including as a partner at PwC.

This content was supplied free to NBR.

Christoph Schumacher and Stuart Henderson

Sun, 09 Oct 2022

Government debt to GDP is a reasonable proxy for the tightrope’s bandwidth, but countries differ in their capacity to leverage this ratio (fiscal hay capacity). For example, the US has a greater leverage capacity than, say, a country whose underlying credit rating is significantly less than the US.

Government debt to GDP is a reasonable proxy for the tightrope’s bandwidth, but countries differ in their capacity to leverage this ratio (fiscal hay capacity). For example, the US has a greater leverage capacity than, say, a country whose underlying credit rating is significantly less than the US.