Streets and their sidewalks – the main public places of a city – are its most vital organs: Jane Jacobs

Many commercial buildings fail today not solely because of decreased occupants due to a work-from-home trend. They are failing because of a deficit of “street activation”. They need to catch up in their contribution to the urban realm. Street activation is both the creation of a pedestrian-friendly environment and a visually active building.

As the urban theorist Jane Jacobs (1916-2006) stated, the street and the sidewalk are the most “vital organ of the city”. We should rely on more than just economic activities, such as cafes, at the base of buildings to activate our footpaths. So, don’t we owe it more to our developments and cities to understand the essential ingredients of successful street activation?

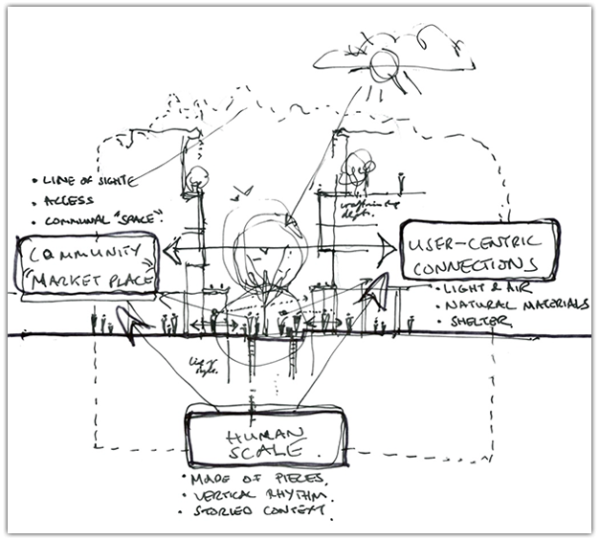

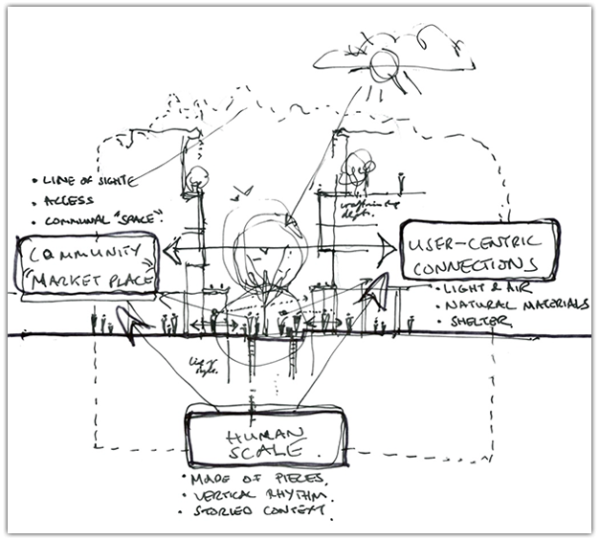

There are three themes to address. First, the design must promote both social interaction and access – a type of “marketplace.” Next, the building edges must enable meaningful connections to the natural environment. By this, we do not mean just the introduction of greenery. Finally, we advocate prioritising appropriate human scale, particularly at the base of large-scale buildings.

We have developed a checklist to ensure that the user-centric needs of the street are included in the final design. These guiding principles for street activation will assist developers, city authorities, urban designers, landscape architects, and architects collaborate to achieve better outcomes.

User-centric connections to the environment

The Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was one of the great urban thinkers of the 20th century. Although sometimes misinterpreted, Le Corbusier prioritised light and air in his urban design. He believed the "history of architecture is the history of the struggle for light".

Le Corbusier felt that access to light and trees was more important in design than steel and cement. We need to emphasise the importance of access to this type of amenity. In New Zealand, we must design for local site-specific and climatic conditions. Our annual rainfall ranges between 600mm and 1600mm in most urban areas – a significant difference. Too much sunshine can be a problem as much as too little. The key is researching, harnessing local knowledge, and being aware of prevailing and

seasonal winds. Cities may get windier over time as they get more built out with buildings, especially with the increased volatility of climate change.

In New Zealand cities, verandas are sometimes required under planning conditions for some precincts. This helps create shelter from sun, wind and rain and creates more intimacy for pedestrians at ground level. Protection from the elements not only improves the user experience from a street activation point, but it can also help with the sustainability of the building by mitigating heat loss from drafts.

At street level, using some natural materials where possible is vital. A failure in street activation at ground level often occurs when there is an ill-considered layout of elements, including building services. Suppose aluminium service louvres and large concrete panels are placed incorrectly or poorly detailed. In that case, it can create an unwelcome base. With the introduction of natural materials such as stone, brick, terracotta, brick, timber, or other compatible materials, we can add the human touch. This not only makes the building more welcoming but also creates street appeal.

Remember that even large panes of clear glazing can fail in activation terms when commercial or leasing advertising graphic films are introduced. The design team should select natural materials that are durable for the local climate, timeless in taste, and easy to clean and maintain.

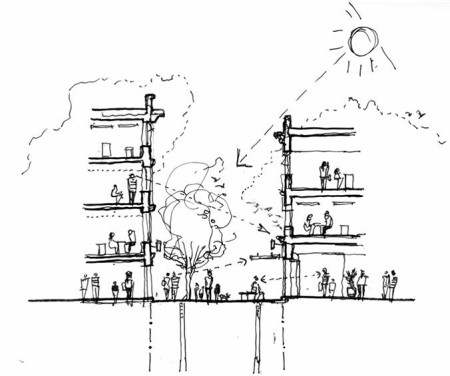

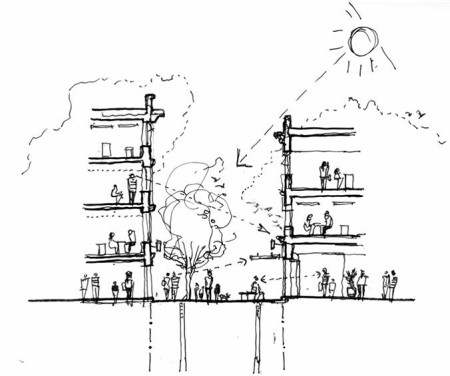

Street Activation Study, Auckland. Image: Voss, Arbuthnot and Wilson.

Community and marketplace connection

In City Life at Street Life, a 2019 report by the City of Seattle, it states that the streets make up the most significant part of the public realm. In Greater Seattle, rights of way, streets, alleys and footpaths comprise 40% of the land area. Therefore, it follows that street activation is so important because “the street level of buildings is a critical part of the public realm, offering a place to travel, eat out, exercise, shop and meet others”.

A vital aspect of this social and economic activity is creating a welcoming “line of sight” into and from the buildings. The entry points need to be clearly defined and prominent. In our experience, we must be careful about blocking too much of the street with excessive greenery, planter boxes and street furniture because it inhibits visual connection and can disrupt visually and mobility-impaired users. The designer must lay out streets and squares to facilitate social interaction, contributing much more to an active city than ground-floor retail. Even before the commercial pressures of the global pandemic, there was a limit on just how much retail and hospitality space is sustainable in the inner city and suburbs.

Accessibility into buildings is not just about designing responsibly for statutory compliance – such as ramps for wheelchair users. It is also about providing safety and welcoming invitations for all diverse groups. The design objectives must move to achieve more active collaboration between architects, urban designers, landscape architects, engineers and planning authorities to achieve this inclusive design outcome.

For example, Plymouth City Council in the UK correctly consulted and involved the dementia community so that they could "inform the measures that will be implemented" in their urban design. The Ministry of Health in New Zealand estimates that the country will have 78,000 people with dementia by 2026. Among other diverse groups, this is a significant and growing part of our community – they need to be catered for on our streets and footpaths. What is suitable for people with dementia is fundamentally sound under Universal Design. Laying out the street design properly and insuring places are suitable for walking will contribute to streetscape activation; the adjacent buildings need obvious functions and welcome entries. Together, this will promote the vibrant street life that city dwellers crave.

The public parks movement started in the 1830s – a desire to improve health in overcrowded industrial towns. Pukekawa / Auckland Domain, set aside in 1843, is Auckland's oldest park. These types of green spaces offer natural restorative relief to city dwellers. This park also provides recreational amenities, communal gathering opportunities and commercial activities. Our local Pasifika communities have replicated their “marketplace” model with great success in the urban fabric of South Auckland. This interaction between the seller and purchaser is not just about financial transactions but also social connection, bonding and meaning.

First Nation people greatly value this form of social interaction in the urban realm and rural communities. Street activation must create a pleasant backdrop for this commercial and social activity – space, comfort and atmosphere. Street activation based on the community space philosophy will build more urban resilience as we face increased challenges due to climate change.

O’Connell Street in Auckland. Images demonstrate vertical rhythm, depth of façade and natural materiality. Photo: Richard Voss.

Introduction of welcoming human scale

One of the ingredients of a successful streetscape is to respond to the human scale. This means façade elements are made from smaller pieces. These sizes are similar to those of the human body. In London today, many new developments still have brickwork at the base of the building. Bricks are individually on a tiny scale – they come from the brick size the human hand can lay. People can relate their scale to something this size.

The renowned Danish urban designer Jan Gehl

discusses the importance of regular “vertical rhythm” in the street. He believes that every four, five or six metres, a change will generate variety and interest for pedestrians on the footpath and we can add depth to the façade alongside scale and rhythm.

A great example is the heritage buildings on O'Connell Street in Auckland. Many buildings have deep window reveals or column pilasters, often in natural stone. When you look up to the sky in O'Connell Street, which is now pedestrian-friendly, you see

an array of detailed roof cornices above.

Heritage architecture is about "bricks and mortar" and the storied past - people and events. It concerns the people who funded, designed and built the streets and buildings. In New Zealand, the

Te Aranga Principles provide a framework for clients and design teams to respect the ancestral lands of indigenous culture. In our experience, this cultural narrative, alongside sustainability initiatives, can contribute to the buy-in of end users and the people who build the project. Finally, an artist’s specific work or contribution to decorative elements in the building can commemorate past events and further reinforce community engagement. A city such as Auckland does not just have sculptures in parks and town squares but often on busy streets.

They tell the city's story to locals and visitors alike. The lowest two building levels can positively impact pedestrians regarding street activation. Therefore, we should spend money on materials here; all will appreciate the visual appearance. For a commercial development, the first impressions need to be of sound quality and contribute to the overall success of the development inside. On the ground floor, we can demonstrate the skill and craft of the builder and provide long-term durability. In large-scale Victorian buildings all over the globe, the building scale and materiality are often broken down into elements such as bay windows, arcades, canopies, portals and porches. Modern buildings in many major urban centres have become more extensive, but we would do well to learn from the successful outcomes of past design endeavours.

Street Activation First Principles, Auckland. Image: Voss, Arbuthnot and Wilson.

Three fundamentals

Street activation is achieved by designing around three fundamental human-centric fundamentals.

First, there must be an appropriate connection to the natural environment. Secondly, we must create an accessible "marketplace" for human interaction. Thirdly, the streets and buildings that form street activation must prioritise the use of human scale.

If we get these right, we will surely know by the presence of people in our streets.

As Jan Gehl rightly said: “A good city is like a good party – people stay longer than really necessary because they are enjoying themselves.”

For a commercial development to be successful in the long term, it must understand and address street activation. This is a back-to-basics approach for all design professions – consider the connections to the natural environment, the creation of social market space and the priority of human scale.

With successful and cross-disciplinary design intentions, we can create vibrant cities where people wish to stay longer.

Richard Voss is an architect based in Auckland who has worked internationally on urban design, architecture, and workplace design.Mark Arbuthnot is a town planner based in Auckland.

Carin Wilson is a Māori artist, designer, and cultural adviser based in Northland.

This guest analysis was supplied free to NBR and was not commissioned.

Richard Voss, Mark Arbuthnot and Carin Wilson

Sat, 06 Apr 2024