How to deal with ‘saboteurs’ at work

ANALYSIS: There are ways to combat the ‘inner laziness’ of some staff.

Lazy employees can prevent innovation and sabotage their colleagues.

ANALYSIS: There are ways to combat the ‘inner laziness’ of some staff.

Lazy employees can prevent innovation and sabotage their colleagues.

When sorting out some books in the cellar recently, I came across an amazingly astute and useful book. It is as relevant now as when it came out 20 years ago.

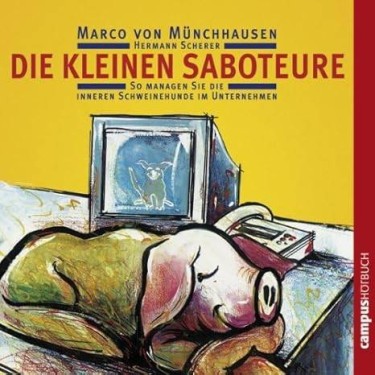

Die Kleinen Saboteure, or The Little Saboteurs, by Marco von Münchhausen and Hermann Scherer (Campus Verlag 2003), deals with the issue of Schweinehunde. Translated as ‘pig dogs’, these are people who cause delays, indecision, and stagnation in organisations by disrupting processes and finding all sorts of reasons to prevent change.

The concept is basically about ‘inner laziness’ and is quite amusing to read about, but the organisational reality is not so funny.

The authors suggest several principles that drive such individuals. The first is that, as long as no one notices, they can maintain the status quo, making sure any new projects or ideas come to nothing. Schweinehunde always have endless excuses and rationalisations ready, even before anything annoyingly new and different is proposed. They block change, prevent the implementation of innovative projects, and sabotage the professional development of individual colleagues. They make sure any decisions made are soon forgotten and, if this does not work, they bring work to a rapid standstill. They often find a scapegoat, so they remain undetected themselves.

Let’s have a look at their usual bag of tricks. The saboteurs have various favourite arguments for inaction such as: ‘This problem cannot be solved in the prevailing environment’, ‘No company can do this’, ‘With our equipment, this cannot be done’, ‘The market is not ready for this’, and ‘Others have failed with this before’. In other words: ‘This just won’t work and, if you try, you will fail.’

There may or may not be some truth in these arguments but, basically, the saboteur simply doesn’t want to take on anything extra or new. If these arguments do not achieve the desired stalemate, you will be told the deadline is too tight, management won’t agree, or the price will be too high. There is an almost unlimited range of excuses for the seasoned professional schweinehund.

This German book has great advice for dealing with ‘pig dogs’ at work.

These people also know a few linguistic tricks. The subjunctive mood is a gift to them: ‘We would have to check the IT costs first’, ‘Sure, we could revisit our marketing strategy’, ‘It would be great to raise our turnover’, or ‘This may be just what we need.’ This conditional phrasing is the perfect way to avoid saying ‘no’, but also not saying ‘yes’.

Vague language is another wonderful way to deal with pending change and new ventures. ‘We will try to implement this’, ‘I will get this activated as soon as possible’, For sure, we really want to monitor our market share more closely’, or ‘First, we can work up to this by developing the right corporate ethos.’ There are endless variations.

Linked to this are outright delaying tactics: ‘We could do this the year after next’, ‘Let’s wait till the economy picks up’, ‘I am happy to do a report on this to check the viability’, ‘This could be done in the summer/winter’, ‘Great concept, but there is no rush because of this, that, and the next thing.’ In Germany, this is known as aufschieberitis, which can be elegantly translated as ‘delayers disease’.

How can one deal with these people and cure them of these dubious tactics?

Identifying them and how they operate is a good start. One can gently point out that the competition is trying very actively to get ahead of the game and there is a need to move quickly. Setting deadlines and tactfully using counter-phrases such as ‘commitment’, ‘rapid outpacing’, and ‘striking while the iron is hot’ may also help.

Backing up your proposals with indisputable facts and figures can move things forward, as can mustering support from non-saboteur colleagues and superiors in a non-threatening manner.

Some managerial principles are so clear and compelling, they are hard to wriggle out of. These include:

Brian Bloch.

As an example of how this works in practice, I know of a medium-sized German company that was not doing well in China. One of its managers had recently done a course on cross-cultural management and learned that blunders of this type are among the most common causes of failure when doing business internationally.

The company’s sales staff in China were offered, on a voluntary basis, an external course on doing business in China. Very few were interested. Most claimed they had no time, or ‘the products sell themselves’, or they were already experienced enough. A couple of staff said they could do their own research.

Those who did the course were amazed at just how much they learned. They discovered, among other things, they didn’t understand their Chinese customers after all, were dealing with the wrong people, were not up to date on the regulatory framework, and failed to deal effectively with trademark and copyright issues. They put much of this knowledge into practice and it really helped.

When this was conveyed to the non-participants, they attributed it to good luck and other external factors. Even worse, they indirectly accused their colleagues of getting ahead through dubious tactics they had gleaned from the course.

Incidentally, when I used to teach cross-cultural management, I used a case study involving an extravagant banquet provided by a Chinese firm for visiting American managers and sales staff. There was an enormous amount of food and one of the Americans gave an after-dinner speech, making what he thought was an ironic joke about their being ‘too little food’. This went down like a lead balloon and the Chinese were seriously offended. One of the key lessons in cross-cultural management is to beware of humour in intercultural contexts.

Brian Bloch is based at the University of Münster (after living and teaching international business in NZ for several years), specialising in English for Academic Research. His main work activity is academic editing in business, economics, and other related fields.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.