When governments should, and should not, fund media

Book Review: Former Time magazine editor reports from the trenches of the information war.

Book Review: Former Time magazine editor reports from the trenches of the information war.

The government plans to spend $55 million supporting ‘public interest’ journalism through to the next election. The first tranche is already open to privately owned media companies.

It does not include what is already being spent on state-owned broadcasting including TVNZ, RNZ and Maori Television or New Zealand On Air, which already funds some forms of journalism.

All up, the government’s total spending on direct media content and indirectly through advertising would be worth many hundreds of millions of dollars.

In most democratic societies, this would be viewed as excessive if not balanced by a thriving private sector media funded by subscriptions and advertising. That equilibrium may be missing, as even the biggest media company, NZME, qualifies for state-funded journalism.

NZME has not indicated it will reject such funding on principle but it is financially healthy enough to go without, continuing to draw its revenue solely from its customers in a free market.

In the US, such direct subsidies or payments would be unthinkable. It has no publicly owned television service and its public radio network is dependent on donations.

Yet its government has a long history of providing news journalism for international audiences. This has mainly been done through the Department of State, the foreign policy and diplomatic arm of the administration.

Losing the war

When a former managing editor of Time magazine, Richard Stengel, in 2014 became Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs in the Obama administration, he inherited a budget of US$1.1 billion compared with US$100m at the world’s best-known weekly news magazine.

His appointment by Secretary of State John Kerry was to reverse the perception that the US government was losing the information war against its autocratic political enemies. These primarily were Russia and ISIS, the militant Islamic organisation that promoted terrorism.

Stengel had an impeccable reputation as an editor and journalist, heightened by his association with Nelson Mandela, resulting in bestselling autobiography (Stengel collaborated with Mandela on this) Long Walk to Freedom (1995) and Mandela’s Way (2010), updated post-Mandela's death and re-issued as Nelson Mandela: Portrait of an Extraordinary Man.

Unlike Britain’s BBC World Service and its TV arm, the broadcasting services of the US – Voice of America, Radio Liberty, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Free Asia – were openly run and funded by a government department.

They were launched in the Cold War and aimed at audiences that had no free media in communist and other dictatorships. Radio had been overtaken by the internet and 24-hour TV news, which in the US was privately owned and at first depended on a domestic audience.

Satellite delivery to audiences around the world changed that, as did competition from state-owned networks that made no secret of their partiality. In English, the best examples were RT (Russia Today), China’s CCTV (now CGTN), and Qatar’s Al Jazeera.

Grappling with diplomacy

Before Stengel could make the necessary changes to introduce 21st-century news platforms, he first had to grapple with the State Department’s culture and methods.

It was resistant to change, risk averse, and prized consensus over initiative. “Diplomacy is an 18th-century profession, managed by a 19th-century bureaucracy using 20th-century technology,” he realised. The department made no effective use of Twitter or other social media.

Unlike the commercial world, the only area of change was in switching jobs. A diplomatic posting might last just two or three years, followed by a similar period back in Washington DC or doing a foreign language course.

Most of an officer’s time was taken up with foraging for the next posting. No one was beholden to a single boss, as they were never in place long enough. This meant decisions were rarely taken seriously, as the default response was to do nothing.

“Actions you signed off on were still not done months or years later,” Stengel says. In some ways, this also reflected Barack Obama’s laidback approach to his job. His first question to any issue was: ‘What is the problem here?’ Often his response was to do nothing if an action would make it worse. Throughout his term, Obama was reluctant to push back even when America was on the losing end.

‘Infantilism of principals’

As the fifth-ranked official in his department, Stengel had 16 or 17 assistants, compared with just one at Time. Their job was to keep the appointments diary full in what is known as the “infantilism of principals”.

This meant keeping the principal so busy each day that they had no time to get anything serious done. At 5pm, everyone went home. Sending emails after hours or during weekends brought no response. When they were answered, the wording was bland and non-committal. Emails were treated as digital Trojan horses – any one could be a trap.

Stengel found out the hard way. One of his personal memos to Kerry, highlighting the failure to combat the ISIS message machine, was leaked to the New York Times as it passed through office procedures before the Secretary had even received or read it. The Times and the Washington Post were often how people in the heavily siloed State Department found out what others were doing.

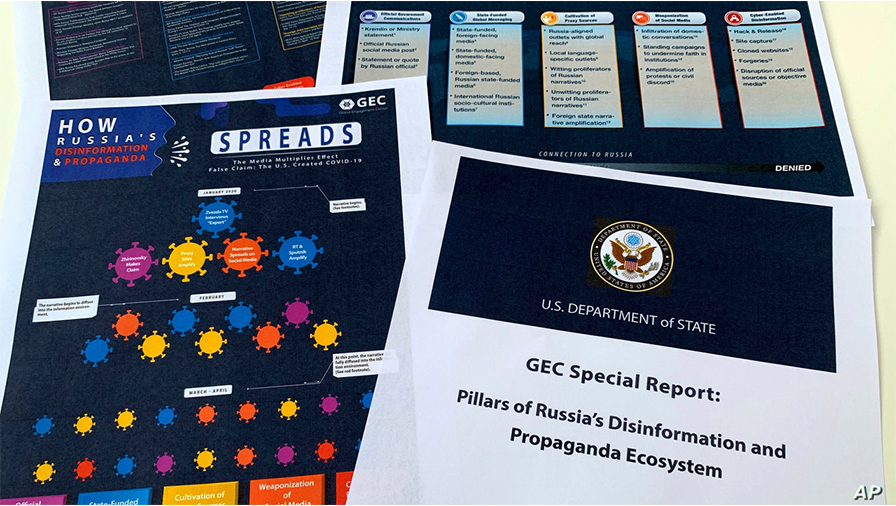

Stengel made it his mission to counter disinformation, originally a neologism from the Russian and based on a century of such activity by the KGB, its predecessors and successors (see my review of Thomas Rid’s Active Measures).

Disinformation is different from its cousins, misinformation and propaganda, by being deliberately false and deceptive. Disinformation is intended to be picked up in the regular media and is especially effective when it highlights Western government failures in social policies such as poverty, homelessness, and race relations.

It had been perfected by Russia and ISIS on issues such as Crimea, Ukraine, Iraq, and Syria.

Disinformation exploited Western public opposition to war as well as destabilising countries that were caught up in them. Russia’s consistent denial of involvement in the shooting down of Malaysian Flight 17 over Ukraine is just one example. The Kremlin denies everything, despite the evidence, and promotes an alternative version, no matter how fantastical.

This exploits the ‘two sides’ concept, on which balance and impartiality in Western journalism depends. Stengel is derisive on how this is used by autocratic regimes: “There aren’t two sides to a lie.” He considers truth is under attack from the disinformation merchants and the Western media are often unaware of how they are being manipulated.

Ministry of Truth

An irony of this sophistication is that when Stengel finally achieved his aim of establishing a network of pro-Western Muslim majority countries promoting moderate Islam, the Global Engagement Center (GEC), it was described by Russia’s Sputnik news agency as the Ministry of Truth, a reference to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Obama signed the GEC into law on December 23, 2016, less than a month before Donald Trump’s inauguration. As you would expect, Trump gets short shrift from Stengel, who at Time resisted efforts by Trump to be on the cover or attend the annual Time 100 party (he had made the cover in 1989 before Stengel was in charge).

Having known Trump since his early days as a self-promoting property tycoon, Stengel dismisses him as “not a presidential candidate, he was a punchline”. Stengel also sees parallels in how Vladimir Putin, ISIS, and Trump “weaponised” the grievance and vulnerability of people who felt marginalised by modernity.

The GEC was largely ignored for its first 18 months under the Trump administration, despite the initiative being partly credited by its overseas partners for the decline and eventual defeat of ISIS.

Stengel’s memoir, Information Wars, ends with the Obama administration and leaves little of a legacy. However, the GEC still exists within the State Department and US government agencies are much more savvy about Russia’s disinformation juggernaut. Kerry is also back as President Joe Biden’s climate envoy.

Stengel offers advice on how disinformation can be fought in the future, including the role of the internet giants in ensuring the primacy of truth in how Western societies conduct themselves. It’s an uphill battle, as many would concede, but vigilance is essential, particularly in those who control and run media organisations.

His experience in government, in charge of an operation that pushed back against the enemies of democracy, is pertinent for its successes and failures. Journalists have a role in promoting the truth, and ensuring they don’t rely on a narrow set of views, while those working in elected governments should also uphold those same standards. When either side fails, society as a whole will be the victim.

Information Wars: How we lost the global battle against disinformation and what we can do about it, by Richard Stengel (Grove Atlantic)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.