Watergate revisited: The tragedy of King Richard

Book Review: How Nixon destroyed his presidency and changed American politics.

Book Review: How Nixon destroyed his presidency and changed American politics.

Four seminal events shaped modern American history – the assassination of President John F Kennedy, the Vietnam war, Watergate, and the 9/11 attacks that launched the ‘War Against Terrorism’. To these, some might later add the presidency of Donald Trump.

Of these, Watergate was significant not for the scale of its crime – a bungled break-in of the national office of the Democratic Party – but for how it changed the nature of politics down to the present day.

The June 1972 burglary was ordered by CREEP, the ominously named Committee for the Re-election of the President, and was botched from the start. But it was the cover-up, ordered by President Richard Nixon, that eventually led to his resignation two years later and the curbing of presidential power.

The story of Watergate has never faded over nearly 50 years. It has produced 60-odd substantial books, including memoirs by most of the main participants. Significant movies and documentaries have followed, from the immediacy of All the President’s Men in 1976 to the History Channel’s six-part docu-drama Watergate, or: How We Learned to Stop an Out of Control President in 2018.

During this period, new information has become available, including 3700 hours of White House tapes; Nixon’s personal papers; diaries; and documents from an array of official departments and agencies.

The latest addition to the flow of books is Michael Dobbs’ King Richard. Dobbs is not to be confused with his namesake and fellow Briton, who rose to prominence in the Conservative party and was an adviser to Prime Minister John Major. Created a life peer in 2010, Lord Dobbs chose fiction as his way of recording political history through novels such as the House of Cards trilogy from 1989 and four on Winston Churchill.

Forensic historian

By contrast, this Michael Dobbs, the Belfast-born journalist, was head of various bureaux in Europe for the Washington Post in the 1980s and 1990s before moving to the US. His approach to history is forensic, having produced an hour-by-hour reconstruction of the Cuban missile crisis, One Minute to Midnight, as part of a trilogy on significant events of the Cold War.

His pivotal period account of Watergate follows the same countdown approach, starting with Inauguration Day, January 20, 1973, after Nixon’s second-term landslide victory in 1972, and ending on July 17. It is structured as a classical tragedy, with a ruler committing a fatal error of judgment stemming from pride or hubris that leads to a crisis. This is followed by a catastrophe in which the hero suffers before ending in resolution or catharsis.

In the first act, the break-in at the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate office complex was already in the news with leaks from the FBI, which was investigating the offenders’ links to the Republicans and the White House itself.

Dobbs recreates Nixon’s conversations with his top aides, primarily PR expert and chief of staff Bob Haldeman and policy adviser John Ehrlichman, as they discuss the inauguration speech and the American withdrawal from Vietnam. By April 1973, when the scandal had gone beyond the point of return, Nixon was torn between deleting the secret conversation tapes and his desire for a full historical record.

“Conceived as a means of recording the triumphs and tribulations of his presidency, the taping system had grown into a monster that Nixon could neither slay nor tame,” Dobbs observes.

Medieval kings

Dobbs draws parallels with the courts of Britain’s three medieval King Richards, after whom Nixon was named. His mother Hannah also named two of his brothers after English kings. While Hannah was thinking of Richard the Crusader (or Lionheart), Dobbs considers Shakespeare’s tragic figure of Richard III as more befitting.

Nixon spent a few hours each day alone in the White House’s Lincoln sitting room, catching up on his reading and listening to classical music. His books were mainly biographies or autobiographies of famous leaders, from Napoleon and Disraeli to Churchill and De Gaulle. Day-to-day business was conducted at the Executive Office Building, across the road from the White House and the West Wing.

Nixon had few friends in the media and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, was getting most of the credit for the Vietnam peace agreement.

“Kissinger was driven by a desire for approval, Nixon by a yearning for revenge,” Dobbs writes. Nixon hadn’t forgotten his treatment over a fund scandal in 1952 when running as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice-president, nor his narrow defeat by Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election.

Like Trump, Nixon believed his loss was due to “voter fraud” in a couple of states but he didn’t complain for fear of a public backlash. His paranoia about his political enemies and the media had intensified once back in office. “The toxic legacy of Vietnam bled into Nixon’s handling of the Watergate scandal and vice-versa,” Dobbs adds.

Deep Throat identified

At this point, Dobbs introduces Mark Felt, deputy director at the FBI, who thought he should be the successor to J Edgar Hoover, who died in May 1972, instead of Patrick Gray, the acting director.

Felt’s identity as the Deep Throat source for Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward was not revealed until 2005, but Dobbs is able to add him to the growing cast of Watergate players.

As the coverup deepened, and those responsible for the break-in faced or were given heavy jail sentences, the embattled White House and the CREEP, headed by lawyer John Mitchell, were besieged by teams of prosecutors, who were making deals with anyone prepared to spill the beans.

One was White House counsel John Dean, who early on described the coverup’s decision-making process as, “like a tragicomedy of misunderstood messages and misinterpreted signals”. Dobbs embellishes Dean’s analogy that unfolding events were like a malignant tumour that had spread far and wide: “From tiny cells, the cancer grew until it consumed, and ultimately destroyed, the presidency.”

I recall reading Dean’s early book on Watergate, Blind Ambition (1976). He followed this up 38 years later with a mammoth 635-page account, The Nixon Defence: What He Knew and When He Knew It.

The final act

Dobbs, using historical analogies that Nixon himself would have approved, likens Watergate to King Henry II’s desire to rid himself of Archbishop Thomas Beckett but not expecting his minions to take it literally.

Ironically, while Nixon was undone by a break-in he didn’t authorise, he scuttled one that he had approved of the Democrat-aligned Brookings Institution, a think-tank.

Dobbs ends his 178-day tragedy a year after Nixon’s resignation, and 16 days after a Supreme Court decision ordering him to hand over his tapes.

Subsequently, the Congress passed a series of measures designed to rein in presidential power: the War Powers Resolution, new campaign-finance rules, new budget procedures, the creation of the Congressional Budget Office, and the independent counsel statute.

While successive presidents have tried to claw back some of those powers, none more than bad loser Trump, Vietnam and Watergate ushered in what some have called an age of cynicism and division that has made American politics almost dysfunctional.

Impeachment became just another part of the political toolkit rather than something that had long been unthinkable. While Nixon himself avoided impeachment through his resignation, Bill Clinton and Trump both survived that ultimate sanction. Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned the former president for any crimes he may have committed.

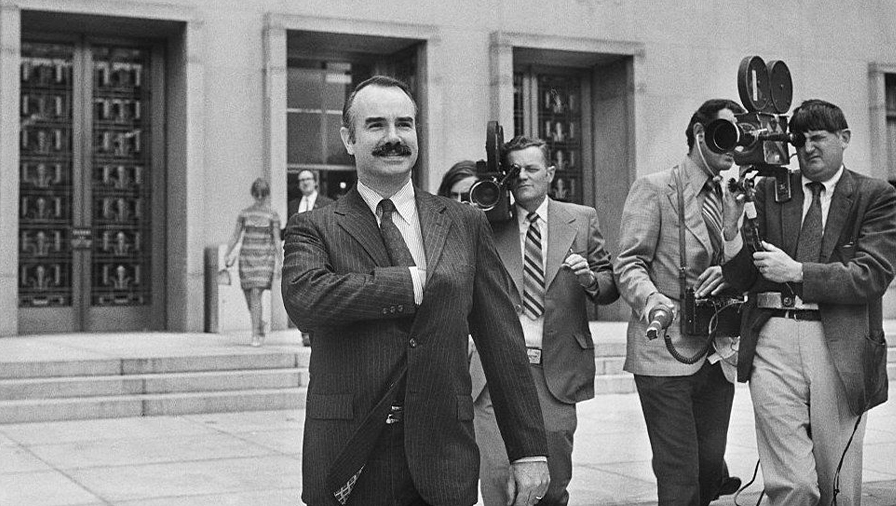

Others were not so fortunate. Mitchell spent 19 months in jail, while Haldeman and Ehrlichman both served 18 months. The longest sentence, four and a half years, went to Gordon Liddy, who led the break-in. While White House special counsel Charles ‘Chuck’ Colson and CREEP deputy Jeb Magruder spent less than a year behind bars, Dean spent four months in a safe house while testifying against other Watergate defendants.

King Richard: Nixon and Watergate: an American tragedy, by Michael Dobbs (Scribe).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.