Space wars: Rival visions at the frontier

Book review: Encounters with the apocalypse underline differing ideologies.

Book review: Encounters with the apocalypse underline differing ideologies.

Only nine days separated two billionaires who privately financed and enjoyed trips into space that will likely herald a new era of such travel.

Sir Richard Branson, backed by Arab oil wealth, took passengers on a two and a half hour journey that included six minutes of weightlessness 80km above Earth. Jeff Bezos’s rocket experience lasted just 10 minutes but it went higher (100km) and faster, producing three minutes of weightlessness.

Needless to say, many considered this a waste of money and a demonstration of the limitless egos of the 1% class. Some would go further, saying it was further proof of capitalism’s basest instincts that will bring about its eventual collapse.

In his recent historical survey of catastrophes, Niall Ferguson predicted climate change wouldn’t be the cause of a future doomsday. Rather, it would probably be another deadly virus outbreak, a massive cyberattack, or the unintended consequences of a breakthrough in nanotechnology or genetic engineering. To that, Stephen Hawking would add an asteroid collision, nuclear war or an ill-fated effect of artificial intelligence.

Merchants of doom

Irish writer Mark O’Connell, a prizewinner for his previous book, To be a Machine, has published a series of lively essays on his encounters with doom merchants called Notes From an Apocalypse. It devotes much attention to billionaires who are planning to survive an end-of-the-world scenario by going underground, including in New Zealand, or by colonising space.

In the first category are American survivalists, also known as ‘preppers’, buying former nuclear bunkers in remote areas of the Mid-West, and their rich Silicon Valley libertarian cousins who can afford hideaways in Central Otago.

O’Connell’s writing has the lightness of George Orwell’s touch as well as a strong ideological slant. But where Orwell addressed the dangers to freedom in versions of socialism, O’Connell sees the preppers as throwbacks to white male patriarchy with the “logical extension of gated community … of capitalism itself”. It’s your choice of whether an apocalypse will result from socialism or capitalism.

A foundation paid for O’Connell to visit New Zealand, where he found no physical evidence of bunkers near Queenstown but it did allow him to spend a lot of time with like-minded people who oppose the sale of land to the likes of Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal and one of Facebook’s initial backers.

O’Connell depicts Thiel as the Sauronesque figure at the centre of a Middle-earth society that is a libertarian alternative to a welfare state in which the individual is a mere cog. These ideas are the basis of The Sovereign Individual, an Ayn Rand-style book for the 21st century.

After checking out Thiel’s bare (except for a hayshed) bit of land at Damper Bay, O’Connell is enamoured with a board game in Auckland called The Founders Paradox by installation artist Simon Denny and Anthony Byrt. This exposes the threats posed by Thiel and Silicon Valley: ‘monopoly’ capitalism, personal data collection, life expansion through technology, bitcoin and cryptocurrency to avoid taxation, and opposition to big government.

That was the time, with Thiel fan John Key still in power, when academia started pushing Max Harris’s The New Zealand Project, which promoted an alternative vision that is now being implemented to varying degrees by the Labour government.

Colonising space

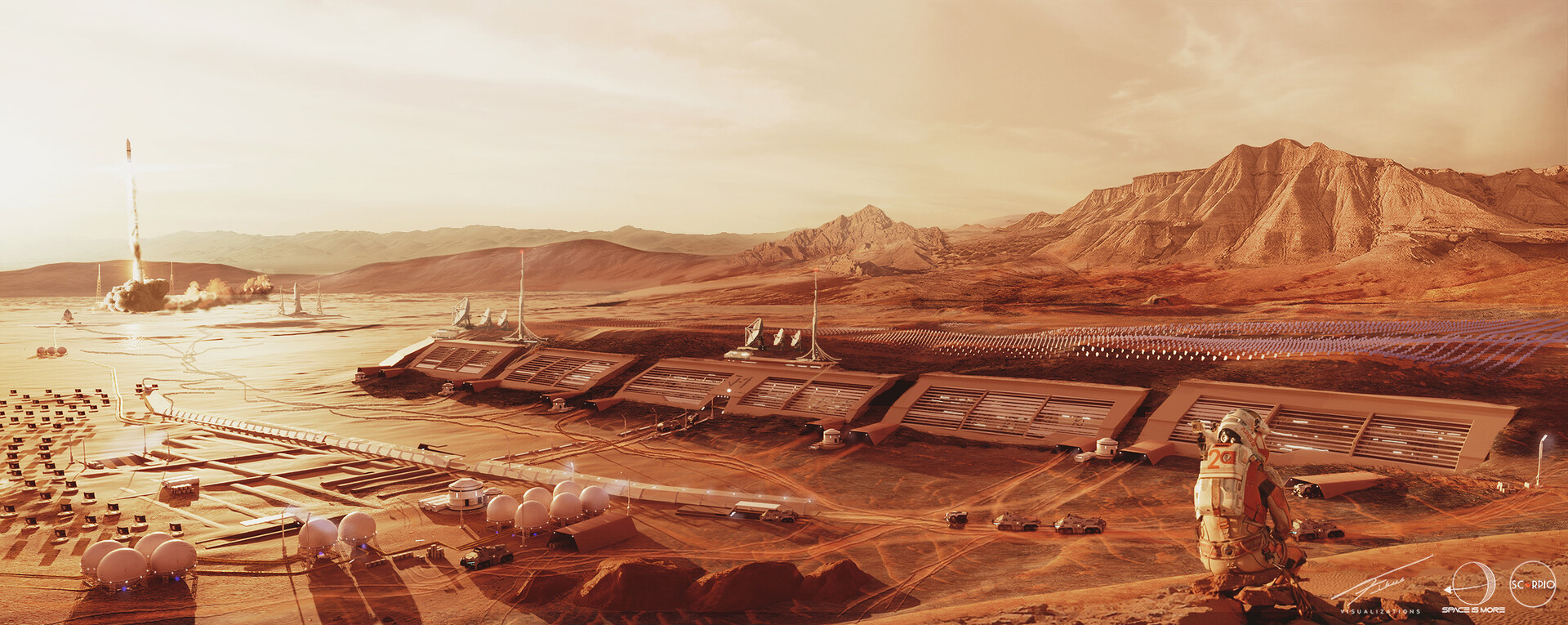

But, back to space, where O’Connell ropes in another billionaire, Elon Musk, with his post-apocalyptic vision of colonising Mars. Rather than just fly people into space like Branson and Bezos, Musk is much further down the track with his private venture, SpaceX, a major contractor to NASA with the Starship rocket.

O’Connell likens a Musk lecture to the Mars Society, a group of enthusiasts for space exploration, to recapturing the “white European spirit of colonial conquest and exploitation”. Furthermore, O’Connell says Musk mythologises America as a country of pioneers, pilgrims and founders of a “new world” while coming from South Africa, “an inverted form of the United States”.

O’Connell then launches another broadside, saying this pining for a “backup” planet is a masculine fantasy and an example of patriarchal power – “a privilege that occurs at the expense of cultivating and sustaining conditions of collective autonomy”.

This obscurantist quote is actually from a Canadian feminist, Sarah Sharma, who argues the space drive is a denial of maternal caring (for the planet Earth).

After linking the Mars Society’s liking for cryptocurrencies back to the anti-capitalist thesis of The Founders Paradox board game, O’Connell dives deeper into literary criticism. This time, Elizabeth Hardwick is quoted for her description of apocalyptic capitalism, “which exists and thrives through expansion of its own frontiers, through a relentless force of deterritorialisation. And it is running out of boundaries to obliterate, nature to exploit”.

Benefits of space

A different view of space exploration comes from Tim Marshall, a former foreign correspondent and diplomatic editor of the UK’s Sky News. Prisoners of Geography showed how every nation’s choices are limited by physical resources and location. The Power of Geography is a follow-up and devotes a chapter on the foreign policy implications of space.

It emphasises the scientific advances and direct benefits that have flowed down into daily life. Products that only exist because of the research carried out for space exploration include: artificial limbs; the insulin pump; the polymers used in firefighters’ heat-resistant suits; shock absorbers to protect buildings during earthquakes; solar cells; water filtration technology; wireless headsets; camera phones; CAT scans; air purifiers; memory foam; home insulation; and LED devices that relieve pain.

But space isn’t just about technological progress. It also concerns international rivalry, which has coalesced into two main groupings. The Artemis Accords have been signed by the world’s democratic states, led by the US, Europe, India and Japan in a “commitment to enhance the welfare of all humankind by co-operating with others to maintain the freedom of space”.

Although Russia and China have joined in various international initiatives, they have not signed the accords and generally see no role for private enterprises such as SpaceX. A legal system is being developed that sets out property and other rights for public and private sectors.

Marshall is hopeful that militarisation of space will be minimised, though the US has announced a Space Force and some are fearful that satellites will become targets in an Earth-based conflict. The positive future uses of space could include moon-based 3D printers making giant solar panels that feed energy back to Earth, and spaceships that can refuel in low-Earth orbit. This would cut the costs and time of long-distance space travel, such as to Mars, to months rather than years.

The mining of meteorites for no-longer ‘rare earth’ minerals would be a top priority. An asteroid called 3554 Amun alone has such wealth valued at US$20 trillion, the same as the GDP of the US.

Apart from space, Marshall profiles the geographic strengths and weaknesses of nine countries or regions that rank below the major powers. His book has an index and a comprehensive bibliography. By contrast, O’Connell’s essays are drawn mainly from his own observations and interviews, with no index or list of sources.

Notes From an Apocalypse, by Mark O’Connell (Granta)

The Power of Geography, by Tim Marshall (Elliott & Thompson)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.