Innovation without the gender gap

Book Review: A Swedish woman’s vision for the economic future

Book Review: A Swedish woman’s vision for the economic future

The golden age of invention in the late 19th century has not been matched since for its impact on economic growth and productivity.

In his seminal study, The Rise and Fall of American Growth (2016), macroeconomist Robert J Gordon identified five great inventions that generated an unrepeatable burst of economic growth from 1920-70. They were: electrification, the internal combustion engine, chemistry, telecommunications, and indoor plumbing.

Others may challenge his choice but most economists would agree total factor productivity growth – as measured by intangibles such as innovation and better institutions – has declined since 1970 to half the average 2% annual rate over those 50 years of the 20th century.

One reason for this stagnation is the time it takes for important innovations to be fully embraced. There are, of course, exceptions, such as the rapid development of vaccines to control the Covid-19 virus pandemic.

Historically, though, innovations such as the wheel were slow to spread after their invention. The oldest examples of the wheel that were unearthed in today’s Slovenia were invented 5000 years ago. Yet many societies before the age of European discovery never found a use for the wheel.

London-based Swedish writer and financial journalist Katrine Marçal (Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?) has put a feminist spin on this in Mother of Invention, a history of technological development and its lack of concern for women.

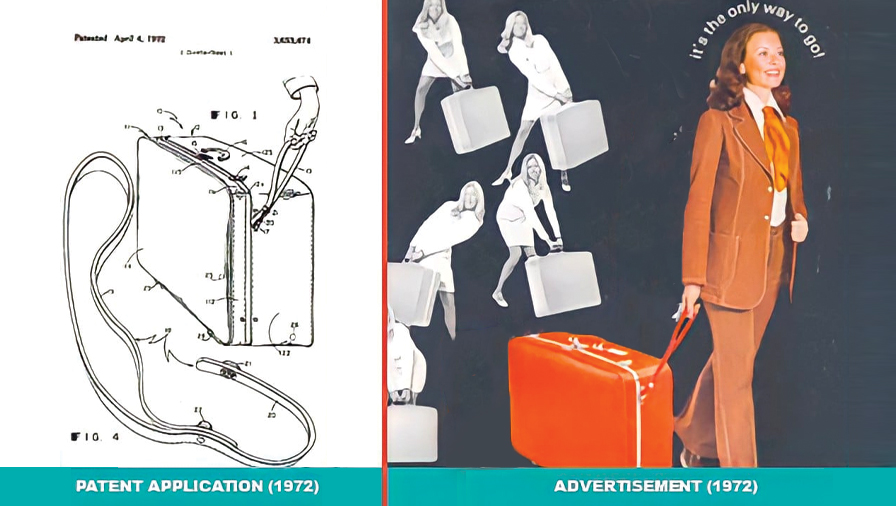

Rolling luggage

Her headline example is the invention of wheeled suitcases. Though patented on several occasions, the product did not take off until Bernard Sadow lodged his patent in 1972 and it was picked up by Jerry Levy, a Macy’s executive. Until then, no one conceived luggage could be other than carried by hand, and usually that of a male.

It wasn’t conceived that women could handle their own luggage, even when they travelled on their own. Sadow’s invention changed that decades too late, but it was in time for women to enjoy independent air travel. Today, rolling luggage has evolved from two wheels into four and even easier to handle.

This is just the scene setter as Marçal digs into the history of hunter-gatherers. Women were the first to develop tools for gardening, cooking, cleaning, and preserving, which led to smelting, pottery and dyeing.

But little remains of these ‘soft’ innovations compared with the men’s ‘hard’ spears and clubs. Marçal observes that textiles and pottery were more pivotal in the advance of civilisation than bronze and iron.

Age of transport

Marçal makes no reference to Gordon’s great inventions in her extensive list of sources but she uses motor car engines as an example of how men’s needs were paramount.

At the start of the 20th century, battery-powered cars competed with fossil-fuelled ones. The electric vehicles were cleaner and quieter but limited to a 60km range on paved streets. Marketers identified them as primarily for women.

Men were sold the noisier and dirtier internal combustion engines that could easily be refuelled and travel on unpaved roads. Crank-starting of early models was strictly a masculine task.

This uneven contest decided the evolution of motor vehicles for the rest of the century. Technology that eliminates carbon emissions is only now reversing the course of history.

Coming of computers

Gordon’s analytical work focused on the impact of automation on the durable manufacturing sector. Furthermore, he emphasised the marginal effects of productivity gains on living standards compared with the earlier great inventions.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, he downplayed the role of computer technology in economic growth in the latter 20th century and its significantly reduced productivity gains.

Marçal covers this from a different perspective with analogies of people versus machines, or more crudely, male versus female characteristics.

Robots are good at repetitive functions, such as calculations. But they lack instinctive means of thought and are poor at what people can do intuitively after years of experience. This is sometimes known as the Polanyi Paradox, named after another economist, who said: “We know more than we can tell.”

This leads to another paradox, Moravec’s, that artificial intelligence is good at difficult tasks that take years to learn. But AI lacks the computational abilities of an infant when it comes to learning simple things such as walking and opening doors. This extends to pursuits such as cycling and hopscotch through to household duties and sorting laundry.

“We still haven’t created machines that are like people,” Marçal writes. “Instead, we have organised humans like machines.”

Future of work

Marçal’s biggest gripe about computing is that women were the first human calculators in what was then a low-paid profession. The film Hidden Figures is about the bright black women who did the maths for the Apollo moon missions.

But when computers eventually took over, coding became a better-paid and male-dominated profession from which women were largely excluded. It’s a theme Marçal expands on when she considers the future of work for both men and women.

That will depend on who gets the say on whether technology is harnessed for the benefit of people, or whether it will be distorted to other purposes. An example is China’s extensive use of surveillance and identification that could eventually lead to an unthinking society.

The gender gap in remuneration rates could be worsened or closed, depending on which jobs are made redundant by automation. In the author’s home country, Sweden, the workforce is the most gender-segregated in Europe, and the pay gap is a relatively wide 30% (in contrast, New Zealand’s public service has a pay gap of just 5.7% in the top three tiers).

The good news is that many of the ‘feminised’ professions – health, education, law, communications and media, human resources, and personal service – are those that depend on the ‘soft’ strengths of important feelings, relationships, empathy and human contact. The downside is that while these qualities are lacking in robotics, they are often accompanied by lower pay rates.

Reaching conclusions

Marçal makes a persuasive case in history for why women should not be excluded from the gains or credit for technological advances. For example, it doesn’t make sense to discriminate against who gets venture capital, a subject on which Marçal is particularly forthright.

“There’s nothing wrong with men. But there is something wrong with a system that shuts women out,” she writes.

Recognition that motherhood requires commercial skills and has enabled many women to do well in business should not prevent access to capital or prejudice the traditional earning role of the male. But men do have a problem if they refuse to change.

This brings Marçal to her most controversial conclusions, riffing on Greta Thunberg’s accusation that world leaders are lacking in action on climate change. The answer to her, “How dare you?” is that they are risking the planet in the hope that solutions will turn up in the future.

‘There’s nothing wrong with men. But there is something wrong with a system that shuts women out.’

“What you choose to do and not to do about the climate emergency is directly linked to your views on technology,” Marçal states, elaborating on American science writer Charles Mann’s description of the environmental debate as a battle between ‘wizards’ and ‘prophets’ – a conflict that pits believers in future innovation against those who want to avoid doom by resisting harmful change.

The gender spin on this, Marçal argues, is that both the ‘wizards’ and ‘prophets’ have often been wronging the past by ignoring or delaying the impact of technology on women. That simple matter of why wheels on suitcases didn’t occur decades earlier was due to a gender bias that this invention wasn’t worthy enough.

The climate issue need not be a dichotomy, either, if it’s possible to imagine another world and solutions are found before it even exists. This is provocative thinking that requires gender differences to be fused and all people become equally engaged in pursuing a joint economic future.

Mother of Invention: How good ideas get ignored in an economy built for men, by Katrine Marçal. Translated from Swedish by Alex Fleming (HarperCollins). Photo credit: Liam Brown

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.