Identity politics defuses May Day militancy

Book Review: Centennial history of the Labour Party describes downfall of working-class aspirations.

Book Review: Centennial history of the Labour Party describes downfall of working-class aspirations.

Socialist and workers’ parties around the world this weekend celebrate the international day of labour, or May Day.

But not in New Zealand and a handful of other countries, which separately mark the contribution of the labour movement.

New Zealand’s Labour Day was set on the fourth Monday of October in 1890, one year after the Marxist International Socialist Congress in Paris, or Second International, declared the first May Day. Common to both were demands for an eight-hour day, a call that had been answered for some New Zealand trade unionists as early as 1840 through the efforts of Auckland carpenter Samuel Parnell.

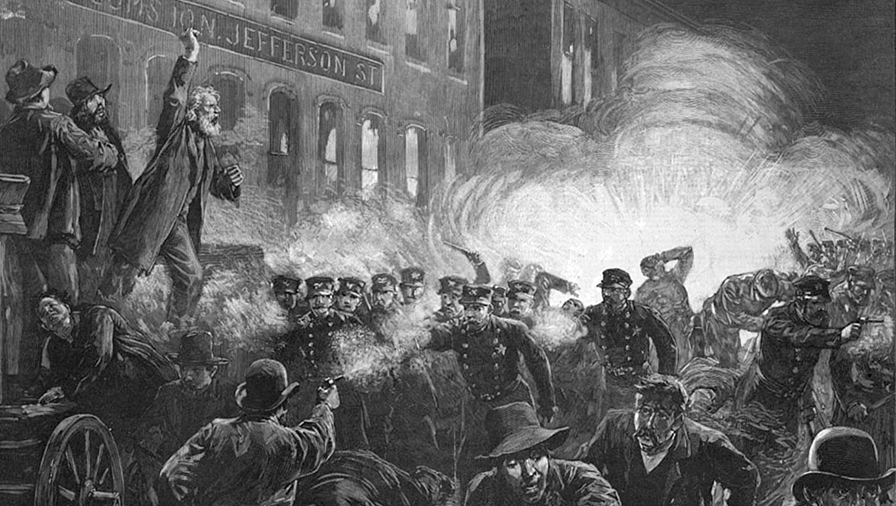

The origins of May Day are American. It marks the Haymarket riot in 1866, when unionists and police clashed violently in Chicago over demands for the eight-hour day.

The US Federal government legislated Labour Day as a statutory holiday in 1894 but decided on the first Monday in September, the same as Canada.

In Australia, May Day is marked only in Queensland and the Northern Territory. The other states have separate Labour Days.

After World War II, May Day became a centrepiece celebration on the communist bloc’s calendar. Social democratic parties in western Europe held rallies, as did other parts of the world where governments permitted demonstrations.

May Day continues to be important in post-Soviet societies, but with an emphasis on nationalism rather than international worker solidarity.

Unions in decline

Events on holidays to celebrate workers are changing, with fewer trade unions to organise them. This reflects economic and social change, as well as a decline in the union movement itself.

Labour Day in New Zealand now has minimal significance, while the only activism on May 1 is to promote the legalisation of cannabis (‘JDay’).

Yet the Labour Party, founded in 1916, has plenty to celebrate since its official founding in 1916 as the political arm of the unions.

Some have suggested its heritage continued the social welfare policies of the New Zealand Liberals from the 1890s.

But in Labour, a centennial history of the Labour Party, Peter Franks and Jim McAloon argue a “Keynesian break” gave New Zealand social democracy a head start over, say, Australia and Britain, while keeping up with the Scandinavians, who had started implementing welfare states before 1940.

New Zealand Labour’s first government in 1935 successfully adopted Keynes’s counter-cyclical policies in the pre-war period but these eluded similar governments in both Australia and the UK until 1945.

McAloon, an associate professor at Victoria University, and Franks, who has written extensively about the union movement, take a sanguine view of the political cycle that has thrust Labour into the role as a disruptor to periods of relative prosperity under alternating moderate conservative governments.

The latter did little to undo the principles of social democracy, thus ensuring a majority of middle-class votes in the 1950s and other periods when times were good.

Existential threat

The authors quote American political scientist Timothy Tilton’s statement on bourgeois Swedish parties that: “…Social Democrats had eliminated the grounds for their existence: they had abolished the impoverished proletariat by making it secure, affluent and unideological.”

When Labour parties in the Anglophone countries subsequently returned to government – in 1957 and 1972 in New Zealand’s case – they did so as “modernisers” espousing egalitarian social reform. But they were defeated by adverse economic circumstances and union militancy that thrived in the heavily regulated environment of 1970s “stagflation”.

When the electoral cycle again went Labour’s way, the appeal of Keynesian policies had run its course and the economic pendulum swung to neoliberalism. The 1980s reforms may have been unpopular with Labour’s traditional voting base but they were widely accepted because conservative governments were unwilling to implement change.

Franks and McAloon point out that so-called ‘transformational’ change is rare in New Zealand’s political history. Since 1975, there has been no one-term government and only two since 1930.

Two-term governments are also rare: the only one since 1935 was the fourth Labour government of David Lange.

Aversion to change

Other characteristics signal deep-seated conservatism against change even in times of crisis. National was re-elected to a second term after the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011, buoyed by the All Blacks winning the Rugby World Cup in election year.

Labour echoed that when it, too, was re-elected during last year’s Covic-19 pandemic.

This preparedness to endorse governments has an equal but negative impact on opposition parties.

Labour’s heavy defeats in 1990 and again in 2011 brought changes in leadership and policy approaches. The same happened to National in 1999, 2002 and 2020. Sometimes these changes are panic-driven.

For example, Franks and McAloon think the decision to dump David Shearer as leader ahead of the 2014 election was a failure of nerve. The hiatus hurt Labour’s chances but the switch to Jacinda Ardern at the next election proved a triumph.

Labour’s recovery after the implosion of the Lange government is also instructive. Helen Clark renounced neoliberalism in 1995, leading into the 1996 election, the first under MMP.

Just three years later, Labour had re-asserted its position to lead a coalition government for three terms. This was based, Franks and McAloon say, on adherence to unity, discipline and strong leadership.

Notably, Clark and her finance minister, Sir Michael Cullen, did not rush to implement radical change; instead, they cemented in most of the neoliberal policies that Labour had selectively renounced.

However, they did signal that Labour was still committed to addressing inequality through income redistribution; public provision of health, education, and housing; and the state guiding economic development.

Moving to the present, Labour has demonstrated its ability to stick to this formula.

Previous studies

Long-range studies of political parties do not often occur, so Labour is a valuable contribution. The last study of the National Party was done by Barry Gustafson in 1986, following his one of Labour in 1980.

Bruce Brown published his history of Labour up to 1940 in 1962. Both authors wrote as if Labour’s best days were behind it.

Most political history is written in biographies and autobiographies. The past year has produced just two books of substance, featuring Jim Bolger and Bill Birch, both of whom concluded their careers last century.

Academic historian Michael Bassett, a participant in the third and fourth Labour governments, wrote personal memoirs of both in 1976 and 2008 respectively, while Marilyn Waring left it until 2019 to publish an account of her ‘political years’ (1975-84).

On policy formation, Franks and McAloon note the tone of much writing about Labour politics is about ideology, mainly lamenting missed opportunities to implement a more radical – that is, socialist – programme.

Those calls are still heard today, despite the Ardern-led government proposing or implementing sweeping changes in education, health and local government, to name just three areas where it has always been activist. It is also reversing some key elements of neoliberalism, such as independence of the Reserve Bank and state-owned enterprises.

Changing identities

Franks and McAloon play down the role of ideology in the Labour movement, restricting their observations to the pragmatic issues of day-to-day government. They also skirt over the replacement of traditional working-class issues by favouritism of certain groups through identity politics.

Labour now measures its record in terms of whether it counters the perceived disadvantages of women, Māori and Pasifika rather than advancing living standards for all.

This is a marked change from Labour’s reluctance to pursue quota-based or separatist policies in the Clark-Cullen years, which produced KiwiSaver, New Zealand Superannuation Fund and Working For Families, as well as restoring the state’s involvement in business through Air New Zealand, Kiwibank and KiwiRail.

The intellectual groundwork against neoliberalism in the universities over several decades helped create the core of tertiary-educated and formerly state-employed Labour MPs. This lack of working-class representatives was complemented by the failure of National and Act to articulate fresh voter appeal for moderate conservatism and classical liberalism.

Franks and McAloon, writing before the 2017 election, present Labour as providing stable government with a legacy of an independent foreign policy, support for the arts and culture, Treaty of Waitangi obligations, and fiscal responsibility that survived nine years of National rule.

It’s too early to assess the achievements of the sixth Labour government. As for the future of social democracy, that will depend on how much identity politics, including green economics, can suppress traditional working class demands for higher standards of living from the capitalist system.

Labour: The New Zealand Labour Party 1916-2016, by Peter Franks and Jim McAloon (Victoria University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.