Falcons first find their target, then strike

Book Review: The Iraqi spies who hunted the terrorist leaders of Al Qaeda and Isis.

Book Review: The Iraqi spies who hunted the terrorist leaders of Al Qaeda and Isis.

Few examples of the printed medium are as compelling as espionage stories, whether fact or fiction.

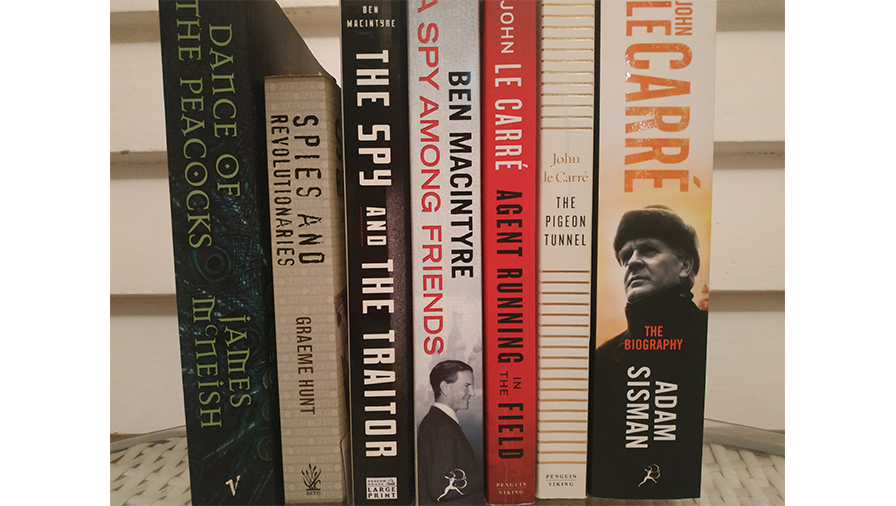

Occasionally they are a mixture of both, best exemplified by the novels and memoirs of John le Carré, a pseudonym for David Cornwell.

He died on December 12 last year, aged 89, leaving an unmatched legacy of Cold War spy thrillers, of which The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) was the first to become a bestseller. His latest, Agent Running in the Field (2019), was preceded by a memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel (2016).

The latter was partly to correct some impressions from Adam Sisman’s mammoth 2015 biography and illuminate real events that appeared in fictional form.

All were informed by Cornwell’s early career as a German-speaking British diplomat and stints at MI5 and MI6, while he wrote his first books. His work was so influential that many of his spy terms, such as ‘mole’, were later picked up and used by the organisations themselves.

Real-life spies

The factual side of Cold War espionage is best represented by Ben Macintyre, a Sunday Times journalist whose A Spy Among Friends (2014) and The Spy and the Traitor (2018) are accounts of Kim Philby and double agent Oleg Gordievsky, respectively.

Macintyre’s latest is Agent Sonya about Ursula Kuczynski, or Ruth Werner, a German-born Soviet spy in Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. She was never detected and returned in 1950 to East Germany where she died in 2000 aged 93.

Two other recent non-fiction Cold War books are Trevor Barnes’ Dead Doubles, about the Portland spy ring, and Simon Kuper’s The Happy Traitor, about George Blake who, like Philby, lived the rest of his life in Moscow.

The Portland ring involved Morris and Lona Cohen, two American communists who obtained New Zealand passports in Paris in 1952 as Peter and Helen Kroger. They also ended up in Moscow.

Barnes confirms the passports were issued by the legation’s head Desmond (Paddy) Costello, a Soviet sympathiser whose activities are recounted in James McNeish’s Dance of the Peacocks (2003) and Graeme Hunt’s Spies and Revolutionaries (2003).

War on terror

Sensational modern-day espionage exploits didn’t end with the Cold War. Many emanated from the Middle East, where Israel’s Mossad penetrated the highest political levels of Egypt and Syria. Usually, these examples only emerge after such agents are caught and, in most cases, executed.

Most attention in that region has focused on the first Gulf War and the subsequent war against jihadist terrorism, led by the US against its main proponents, Al Qaeda and the Islamic State (Isis).

The two invasions of Iraq, sparked initially by Saddam Hussein’s attack on Kuwait in 1990, and followed by his overthrow in 2003 after the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington DC, required a substantial intelligence operation.

Not as well known is the work of Iraq’s own espionage service, whose network of informants and local knowledge were largely responsible for identifying and tracking down leaders of those two terrorist organisations.

That story has now been told by Margaret Coker, an award-winning journalist who from 2003-19 reported from the Middle East for the Wall Street Journal and subsequently was the Baghdad bureau chief for the New York Times. Her account, The Spymaster of Baghdad, complements the array of accounts seen through the lens of military officers, soldiers, and policy makers.

Intelligence is hard

“In an era when national armies have the most technologically advanced weaponry in the world, killing terrorists is easy. Finding them is often the biggest challenge,” she writes.

Her account focuses on four people: Abu Ali al-Basra, a military officer appointed to head Prime Minister Nouri’s al-Maliki’s security service, known as the Falcons; brothers Munaf and Harith al-Sudani, who joined the Falcons; and Abrar al-Kubaisi, the radicalised daughter of a blind university professor.

Their personal stories are interwoven, amid much social, religious and other detail, over two decades. This background reveals the deep chasm in Baghdad between the Sunni middle class that flourished under Saddam Hussein and the poorer Shiites, who assumed political power in the post-invasion era.

The al-Sudani brothers, for example, chose military service to improve their social and economic lot, while Abrar became an Isis convert because it seemed the only way Sunnis could resist the Shia majority.

Abu Ali’s background was to lead the Islamic Dawa opposition to the Saddam regime. He went into exile, ending up in Sweden. After the US-led invasion of 2003, he moved back to Iraq.

Promotion to head the Falcons came in 2006 after he realised he could only gain the confidence and support of the American-led forces if he could deliver results the foreigners couldn’t.

This was achieved by tracking down the mastermind behind the unsolved Canal Hotel bombing in 2003. It was the headquarters for the UN and other aid organisations in rebuilding post-Saddam Iraq.

The attack claimed the life of Sergio Vieira de Mello, the Brazilian diplomat whose life has been made into a documentary and a feature film, both called Sergio. The UN and other agencies withdrew from Iraq as a result.

The Falcons identified their suspect as a former commercial airline pilot and Al Qaeda sympathiser whose home provided a base for Sunni bomb squads. He resisted interrogation until the Americans realised they also had his brother in custody. Abu Ali used this as leverage and eventually got the information he wanted.

The hunt continues

The Falcons continued their hunt for other Sunni terrorist leaders, eventually eliminating Al Qaeda. It was replaced by Isis, which rapidly established a base within eastern Iran and neighbouring Syria.

Coker weaves these events through the personal progress of the al-Sudani brothers and Abrar’s embrace of radical Islam. Their stories cross in a plot worthy of le Carré. Abrar was arrested for her role in suicide bombings, while Hanif’s undercover work as a bus driver who could move around Baghdad with ease was eventually put to use in Isis-occupied Mosul.

This is when Coker’s story enters it most gruesome phase. She does not stint in her coverage of the Isis regime’s brutality in its self-styled caliphate. Hanif is exposed and undergoes the worst forms of torture until his death, later found to be videoed on a phone.

End of Isis

The Isis nightmare ended in 2019 when the Falcons lead US special forces to the Isis leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who had gone to ground in Idlib, Syria, near the Turkish border. This had the hallmarks of how Al Qaeda founder Omar bin Laden was found hiding in Pakistan.

This operation occurred as foreign and Iraqi troops, backed by air attacks, finished clearing Isis out of Mosul and the rest of Iraq. Abu Bakr was responsible for some 100,000 civilian deaths.

Coker leaves her story there, as Iraqis pick up the pieces of a fractured country and hope an end to the Sunni insurgency will bring permanent peace. That will mean heeding Pope Frances’s plea during his recent visit for the Sunnis and Shiites to resolve their differences through politics.

Through her choice of Abu Ali, a man of resolve and high repute, Coker provides a reason for like-minded Iraqis to become deserving descendants of the ancient Mesopotamian civilisation.

*****************************************

Footnote: On February 1, London-based online news service Middle East Eye (MME) reported that Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi had assumed control of the Falcon Cell and dismissed its key officials, including Abdul Karim Abd Fadhil, known as Abu Ali al-Basri. This followed two Isis suicide bombings in Baghdad, the first such attacks in years. MME has been linked to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Spymaster of Baghdad: The untold story of the elite intelligence cell that turned the tide against Isis by Margaret Coker (Viking/Penguin Random House)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.