Brain drain, yet again?

Hordes of Kiwis are expected to leave this year as the world beckons. Is contigent labour an option?

Hordes of Kiwis are expected to leave this year as the world beckons. Is contigent labour an option?

Shoeshine did his best to keep New Zealand’s net migration figure positive last year by returning to the Land of the Long White Cloud but, alas, it has dropped into negative territory for the first time since 2012, recording an outflow of 3915 migrants.

It’s not a huge number. In fact, Stats NZ reports that, overall, there were just 45,900 migrant arrivals and 49,800 migrant departures in 2021 – the lowest numbers since 1986 and 1995 respectively.

Interestingly, there were more arrivals of non-NZ citizens (23,200) than there were arrivals of NZ citizens (22,700) in 2021, even with the stringent entry requirements and MIQ in place.

Still, more citizens and non-citizens left than arrived in 2021 overall. That reverses the pre-pandemic trend that saw an average inflow of 57,591 in the years between 2014 and 2019 – peaking at a record net migration of 72,588 arriving people in 2019.

But net migration of NZ citizens, in particular, had been negative since at least 2002. That trend also reversed in 2020, as about 7000 more Kiwis came home than left. An unsurprising outcome given the country’s relative safety and freedom from the pandemic at that time.

As New Zealand’s Covid restrictions mounted during winter and spring, 2021, the northern hemisphere partied through its summer like Covid was over. Jumping on a plane northward to join the irresponsible fun was a tempting proposition for Shoeshine but, having only returned to New Zealand in April 2021, it was not an urge that could be seriously entertained.

However, one can only feel for younger folk, whose travel and off-shore career aspirations have effectively been halted by Covid since March 2020.

MBIE released a report last week giving a “ball-park” estimate that around 50,000 Kiwis might choose to emigrate over the next year as borders reopen.

That’s quite an increase on the 17,900 NZ citizens who emigrated in 2021, which was itself a 17% increase on the 2020 figure.

But it’s not even accounting for “pent up Overseas Experience demand,” said MBIE, although the agency’s officials also left wriggle room at the other end, saying Kiwis might delay travel plans until “the international context settles”.

Even one of those departures can be a huge blow for a Kiwi company that has a typically small or medium-sized workforce, but there’s not much they can do about it, right?

Young people will always want to leave and sample the big wide world, no matter the level of war and pestilence going on across the oceans. More to the point, with house prices high and the cost of living increasing, the better wages on offer overseas are bound to make further periods of net migration an economic reality.

Follow the money

Take the legal sector for example. Shoeshine hung out with plenty of Kiwi lawyers in London. They worked hard, partied harder, and were paid much better than back home. (The rule of thumb used to be that one would get the same salary figure, but in pounds – effectively doubling their earnings.)

Lawyer salaries are continuing to climb in that market, according to trade news site LegalCheek, which ranks law firms by all manner of criteria.

London-headquartered firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer just upped its minimum salary for a newly qualified lawyer to £125,000, while the top 20 highest paying firms (all of them from the US) range between there and £161,700.

In contrast, Kiwi recruitment firm Tyler Wren’s NZ Legal Salary Guide for 2021/22 estimates an Auckland-based senior associate at a top tier firm would be earning $160,000. That estimate could be on the low side according to Shoeshine’s research, but still, the difference is irresistible (even though the GBP/NZD exchange rate is not what it once was).

Obviously Kiwi businesses can’t just throw money at the problem. They will never be able to compete, and they don’t necessarily want to compete – overseas experience leads to valuable upskilling that most local firms would encourage in their employees.

Rather than trying to prevent emigration, the focus needs to be on the immigration end of the equation, suggests Shay Peters, managing director for Australia and New Zealand at global recruitment firm Robert Walters.

Naturally, as a recruiter, Peters wants to improve the attractiveness of New Zealand to foreign workers, but he knows the pain that employers go through trying to find talent and the effect it can have on their business outcomes – and the economy.

“We’ll traditionally see people go offshore with three to five years of experience, but now, because of that condensation of people not being able to go for three years, I think that’s going to be pushed out to maybe even eight or nine years of experience. So that’s a big gap that we’re going to have to fill with people coming from offshore.

“New Zealand faces a transient workforce anyway, because people do go offshore to get different levels of experience. But I think that, because of the condensation due to Covid, we’re going to face a big outflow within the two-year period. I think it will stabilise after that, but this is a period that we’ve got to be concerned about because this is a period where we are already facing a considerable labour shortage.”

Contingent labour

Peters thinks New Zealand needs to open up opportunities for foreign workers as a “contingent labour” option, particularly in professions such as legal and accountancy.

While many Kiwis and Aussies are able to do contract work in the UK, for example, British lawyers are not permitted to do the same here in New Zealand, he says.

“If you’re coming to New Zealand and you’re not necessarily going to stay here as a lawyer or an accountant, you can’t really pick up chunky bits of project work.”

Employers need to get creative to cater for the needs of such a candidate, providing more flexibility to travel around New Zealand and work for different employers, Peters says.

Beyond that, New Zealand workplaces need to play to their strengths. Kiwi professionals in London are renowned for their ability (and willingness) to turn their hand to anything, so perhaps foreigners might appreciate flexing their muscles in a smaller, flatter structure of New Zealand businesses, suggest Peters.

“There’s got to be a way that we can harness that and do it the other way, too,” he says, hopefully.

Dentons Kensington Swan partner and chair Hayden Wilson agrees that it should be easier for UK and Australian qualified lawyers to transfer to New Zealand, given that much of the work they would do here is international anyway. He thinks the New Zealand Law Society should look at the issue.

The Law Society points out that foreign lawyers without a local practising certificate are able to carry out work in two reserved areas: if the work concerns the law of another country, or if the nature of the work means it is essential that the lawyer has knowledge of foreign law.

Practically, many overseas qualified lawyers are employed by law firms and can provide a full range of legal services under the supervision of the firm.

Global connections

Wilson said Dentons Kensington Swan lawyers now benefit from being part of the world’s largest network of law firms (180 cities in 78 countries, including China where it has the largest presence of any global law firm thanks to its part-Chinese ownership), but it only joined Dentons about six weeks prior to the initial Covid lockdown, so the full benefits of that global connection have yet to be fully realised.

Rather than the much-talked about ‘Great Resignation’, Wilson prefers to call it the ‘Great Transition’, and sees plenty of opportunity for New Zealand to soak up international talent.

“A lot of the stories you hear about that are quite negative, that people see it as a threat, but I think it’s important to also see it is an opportunity ... because if people are moving around, that’s a great opportunity to attract and retain really good talent.”

Top Kiwi law firm Simpson Grierson has seen fewer younger lawyers move overseas in the past two years but is expecting change this year, with “really strong” international demand for “the high-quality lawyers that New Zealand produces”, according to the firm’s people and culture director, Jo Stevenson.

But it has seen success in recruiting returning Kiwi lawyers, with more than a third of its legal hires last year being returning alumni. The firm offers all staff and alumni a ‘star search’ payment of up to $10,000 if they introduce a successful candidate, which may have something to do with it.

Stevenson says the firm will also host an alumni function in London during the year, and will be interviewing potential candidates over there.

Closer to home

But Kiwi companies’ main competition is often just across the Ditch, and that doesn’t seem to be changing as the Australian economy starts to gather traction again after Covid.

PwC Australia has taken the unprecedented step of publishing its pay ranges publicly to help it recruit and retain talent. The pay bands, which include superannuation but not bonuses, range from A$55,600 to A$120,000 for the most junior rank of associate, and from A$164,300 to A$362,000 for directors.

That may help PwC Australia compete against northern hemisphere employers, but it also sets a high bar for the Big Four in New Zealand to reach. PwC New Zealand did not immediately respond to a query as to whether it planned to do the same here.

Peters says he’s staunchly pro-New Zealand, but now finds himself with divided loyalties, given his recent promotion to head Robert Walters for the Australia/New Zealand region.

Having just returned from his first trip to Australia since taking the regional role, Peters says his Sydney office’s Legal, Risk and Compliance team has been experiencing an influx of CVs from New Zealand candidates, mostly lawyers. The Brisbane office is seeing requests from employers for Kiwi candidates in the resources, engineering, construction and supply space, and the Melbourne office has seen an increase of New Zealand-based candidates applying for jobs, as well as people just making the move and then seeking work.

Access to secondments

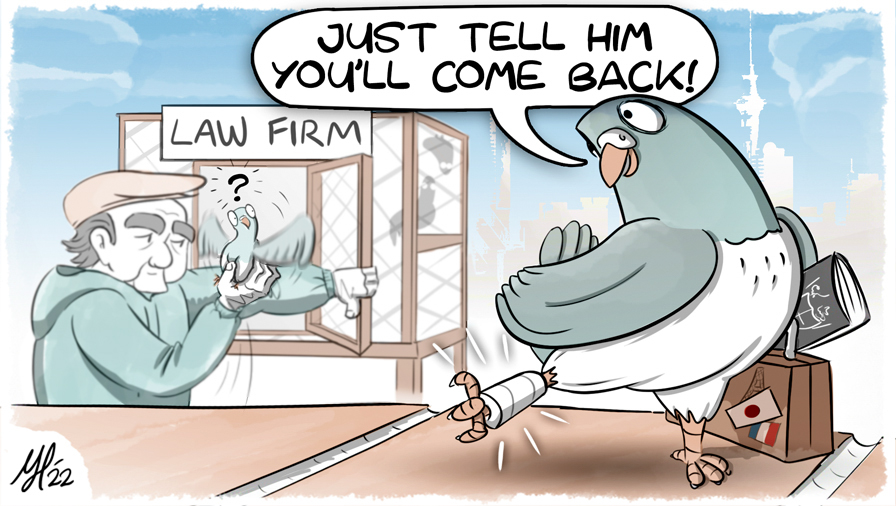

In the face of Australian competition he suggests New Zealand employers give their staff even greater access to secondments, which allow them to travel but retain that tie to the employer.

“It could be that New Zealand law firms create a stronger tie with potential strategic partners in Australia, being other law firms or even a client base, where they can second to for a period of time and come back to New Zealand,” Peters says.

“A lot of New Zealand law firms will have part of their client base within Australia, so instead of secondments within New Zealand, can we be offering secondments in Australia that might still keep that tie to in New Zealand? They might still be coming back to New Zealand, but it gives someone exposure to a different setting or a different market.”

Ultimately, New Zealanders will always want to experience the world and the bigger pay packets and career opportunities that may entail. The key is to keep the doors open at all times, value our off-shore citizens, and that value will eventually flow back to our shores.