Bell’s disastrous campaign to end deafness

Book Review: Telephone inventor’s good intentions damaged the welfare of those he intended to help.

Book Review: Telephone inventor’s good intentions damaged the welfare of those he intended to help.

The calling out of the dead white males who laid the foundations for today’s technologically advanced society has found a new villain.

The inventor of the modern telephone, Alexander Graham Bell, was not a slave owner, an abuser of women, or a colonialist. But he was a monopoly capitalist and had a lifetime’s interest in the science of heredity, verging on eugenics.

Historical revisionism is, of course, justified if it means uncovering aspects of famous men’s lives that would not stand up to scrutiny by today’s standards. Taken to extremes, it can mean removing memorial statues or removing their names from their acts of philanthropy.

In the case of Bell, America’s best-known inventor during the golden age of industrial growth, this revisionism strikes at the heart of capitalist innovation and the wealth it produced.

Bell, who was known most of his life as Aleck and then Alec (the Graham was added when he was 11), has book-length entries in Wikipedia, listing his many achievements, historic sites and roles in such organisations as the National Geographic Society.

In 1936, the US Patent Office named him as the country’s top inventor, while Scotland, on the 150th anniversary of his birth in Edinburgh, issued a one-pound banknote in 1997. A dozen universities granted him honorary degrees and many institutions carry the Bell name.

His surviving businesses include the communications colossus AT&T (owner of Warner Bros); cellphone and transistor inventor Bell Laboratories (winner of nine Nobel Prizes and now part of Nokia); and Verizon, a rival of AT&T.

Personal involvement

Katie Booth, a teacher of writing at the University of Pittsburgh, started her task of taking down Bell’s reputation a decade ago, prompted by the fate of her two deaf grandparents. The result is The Invention of Miracles, a 400-page volume of superb scholarship. Seven pages of acknowledgements are testimony to her research, while the editing is intended for a general rather than academic audience.

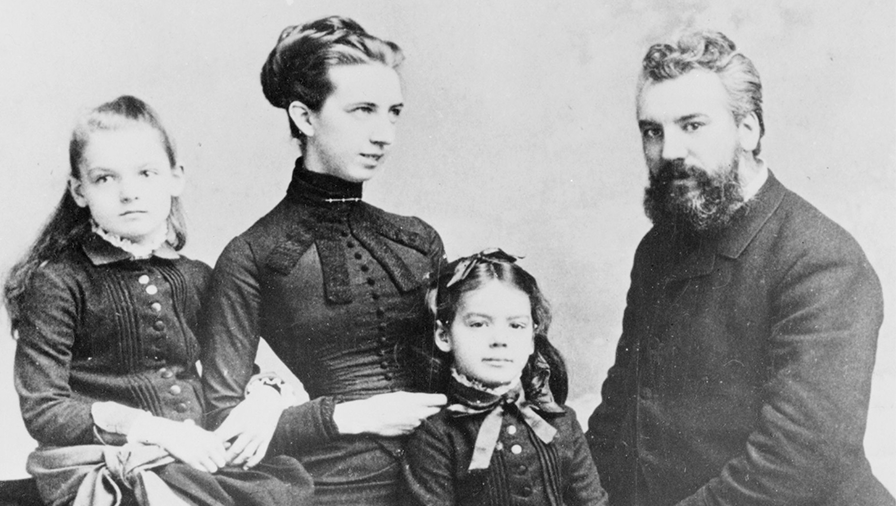

Booth’s personal involvement informs the focus on Bell’s aim to cure deafness, which started at an early age. Bell’s mother started losing her hearing before her teens, while his wife, Mabel Hubbard, lost her hearing from scarlet fever as a child.

The Bells were active elocutionists and speech therapists when they moved to America. Young Alec’s interest in machines began with experiments in talking devices. He developed a Visible Speech alphabet to teach verbal skills to the deaf, a practice known as oralism.

Bell first met Mabel when she was one of his students. She was 16 and he was 26. He was already well known as a teacher (his father Melville inspired George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion character Henry Higgins, later staged and filmed as My Fair Lady).

Bell had access to Boston’s famed MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), then housed in a single building with 300 students. It was experimenting with machines that recorded patterns of sound, which Bell recognised as having potential for his teaching of the deaf.

This was in the mid-1870s, when recently discovered electricity was limited to the telegraph using Morse code. There were no electric power plants, radios or trams.

Meanwhile, Bell’s friendship with Mabel blossomed into romance. Two years after their first meeting, Mabel’s father Gardiner Greene Hubbard agreed to their engagement. Hubbard was one of Boston’s richest businessmen, also with an interest in teaching the deaf. He also backed Bell’s experiments, becoming a founder shareholder in the world’s first telephone company.

Hubbard later founded the National Geographic Society and was its first president, a post assumed by Bell in 1897.

Legal disputes

The early days of the Bell Telephone Company, founded in 1877 a year after being awarded a patent, were punctuated by legal disputes. Bell’s cronyism in Washington DC resulted in his claim being granted just hours ahead of another inventor, Elisha Gray, based in Chicago. A court case ran for years before it was eventually settled in Bell’s favour.

Despite these setbacks, Bell never ignored his interest in the deaf community as a battle raged between the oralists, who wanted the deaf to be part of the hearing community through speech, and those who favoured sign language, which many of the deaf preferred.

Worse, articulation pushed out other areas of learning for the deaf such as history, maths and science. “… [T]he promise of speech was enough to justify whatever sacrifices would need to be made along the way,” Booth writes of oralism’s advocates.

“And while they began their efforts focused on rehabilitative speech, preserving and developing existing speech skills, they were already expanding their reach, taking on congenitally deaf children and working to develop speech from scratch.”

When Bell realised oralism was failing to deliver the expected results, and sign language, or ‘manualism’, with some elements of speech, were more popular, he pushed for a ban.

Heredity studies

By then the telephone business was a thriving monopoly, giving him more time to pursue his interest in researching the hereditary features of deafness. In this he was initially assisted by the fame of Helen Keller, a blind and deaf person who had learned to speak.

At this time, little was known of genetics and studies of family trees showed no definite links to explain deafness from birth.

However, Bell warned against marriages between deaf men and women, though he did not favour legislation to prohibit it. Public opinion in a society devoted to freedom of choice was also opposed to any prohibition of such marriages.

One contemporary study reported people in deaf-deaf marriages were happier than those in which one partner was deaf or even those of hearing couples. The author notes that Keller’s happiness was compromised by her carers, who removed her from any friendship that might result in marriage.

This was a controversial issue, as the eugenics movement was gaining strength as a means to reduce births of the disabled. By 1927, 25 states in the US passed sterilisation laws, later adopted with horrendous effects by Nazi Germany.

Bell was opposed to sterilisation and encouraged Keller in her activism for socialism, feminism, birth control and to encourage men to do more in the kitchen.

This campaign succeeded in almost eliminating the deaf community’s preferred alternative to speech. Oralists had replaced deaf teachers who preferred sign language and, after his death in 1922, Bell was labelled as the father of “audism” – discrimination against the deaf.

Author’s experience

Booth makes her case through the experience of her deaf grandparents, both of whom, along with many of their generation, were denied an education commensurate with their potential. Booth’s grandmother, for example, died in a hospital that had no way of communicating with her in sign language.

For readers outside the deaf community, this is an alarming book with a strong message. Though not deaf herself, Booth learned sign language from her mother and champions the right for a separate “deaf culture” that doesn’t, even with the best intentions, create second-class citizens in a hearing society.

The appearance of sign language during the government’s Covid-19 briefings and other major public events is an assurance that the over-reach of Bell and others is no longer acceptable.

The Invention of Miracles: Language, power, and Alexander Graham Bell’s quest to end deafness, by Katie Booth (Scribe)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This content is supplied free to NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.