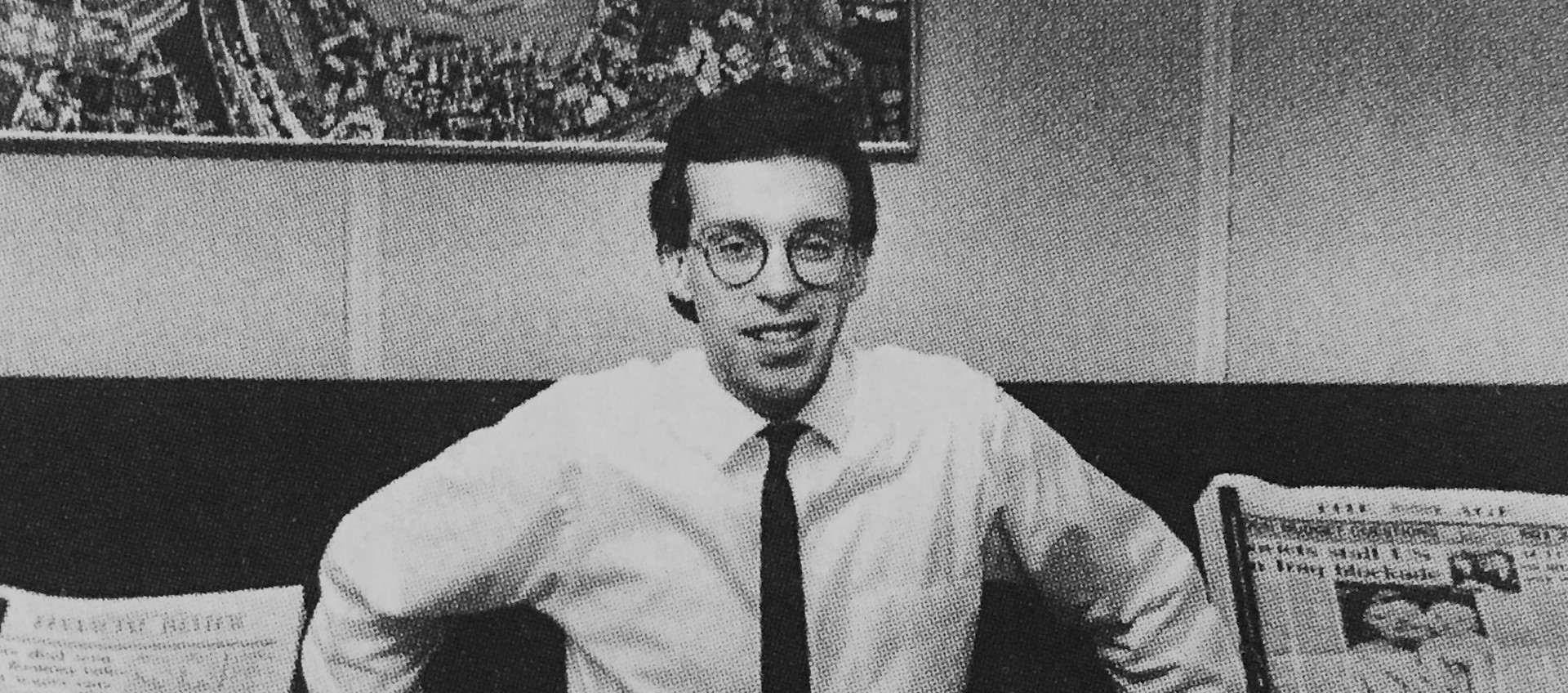

Hugh Rennie QC: Adventures in business journalism

The high-flying barrister is writing a book about his part in founding the NBR 50 years ago.

The high-flying barrister is writing a book about his part in founding the NBR 50 years ago.

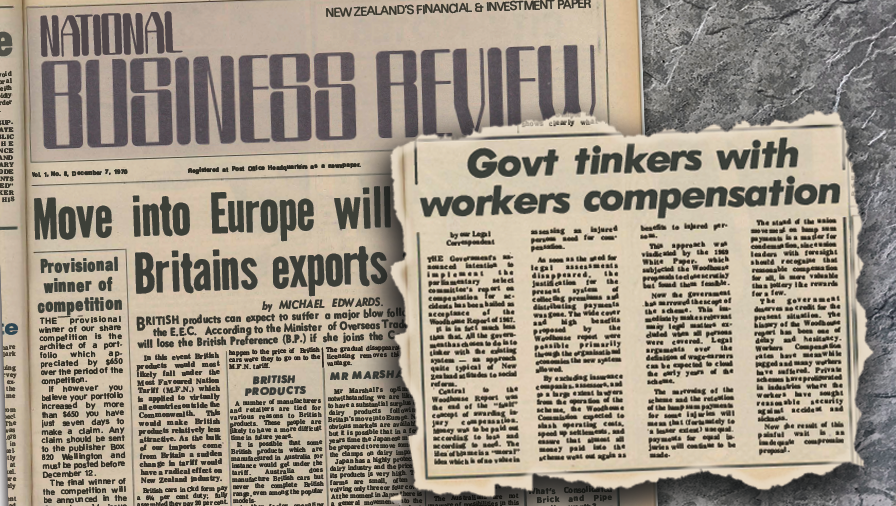

Hugh Rennie QC, one of the original founders of the NBR, which first published 50 years ago today, always thought his legal training would come in handy if some of the targets of the paper’s investigations took the pip at the coverage and decided to sue.

In fact, the paper was served with millions in defamation writs over the 18 years Rennie was involved with it, from 1970 until 1988, even though it only paid out less than $10,000 as a result of his vigorous legal safeguarding.

But the first defamation suit did not come as a result of an irked company executive, shady loan shark, or misbehaving millionaire. The first defamation suit taken against the NBR was from a woman whose photo had inadvertently graced a feature on how the fairer sex were becoming easier to seduce in the booming nightlife scene in Auckland in the early 1970s.

It was 1971, less than a year into publication, and the paper had expanded into book reviews, wine, art, and cultural reporting as a result of an idea from new features editor and marketing expert Ian Grant. He declared the readers – mainly men at that stage – “had a life after 5pm”.

The ‘After 5’ section was a hit with readers, but ran into the aforementioned trouble with its feature on ‘the new lifestyle’ in Auckland. After getting the woman’s permission to take her photograph, it was duly whacked into a story suggesting it had become possible to go out to bars and pick up women.

“She was doubly angry, not only because she never would have agreed had she known [the thrust of the article] but secondly, if you looked closely at the photo you could see her partner’s drink next to hers – he just happened to be out of shot,” Rennie remembers.

“So we had to work our way out of that one and that was highly embarrassing. And we learned a good lesson.”

Needless to say, defaming random women was not a focus of the newly minted NBR of the early 1970s. Instead, a group of young Wellingtonians fresh out of university sought to upend the staid business and political establishment of the time – by doing away with glowing chief executive profiles and advertorial, and putting hard-hitting business journalism in its place.

In his recollection, Rennie says NBR was shaking up the “old boys” who had dominated the establishment scene for too long. “We weren’t old boys, we were wrong-side-of-the-tracks young troublemakers.”

The QC is writing a personal memoir, called A Business Revolution – the first 21 years of National Business Review (Fraser Books Publishing) – about those tumultuous early years, covering the period from establishment in 1970 until 1991, when Barry Colman of Liberty Press acquired 100% ownership.

Unbelievably, Rennie, who held down not just a demanding day job as a commercial and public law barrister but was also favoured by successive governments to head up a host of bodies and boards, including as chair of the Broadcasting Corporation of NZ (BCNZ) between 1984-88, only relinquished his role as chair of NBR in 1987, and as copy checker of the paper in 1991.

The legal wrangling over the paper’s ownership that characterised his final year as chair finally did it for him, after huge amounts of toil to keep the, sometimes frankly financial unviable, publication going.

But he’s proud of its legacy, and of his part in contributing to the establishment of proper business journalism in New Zealand. Of the practice, he says: “Once it was a desert. Now it has some trees.”

Beginnings

At uni in the 1960s, Rennie had run the student mag Salient for a year before graduating and, while he trained in law, he held an abiding interest in journalism – “I actually had two job offers in journalism and none in law on leaving university,” he notes.

In 1970, he was contacted by a chap who had worked with him on Salient, then 23-year-old fellow-Whanganui native Henry Newrick, who had gone into advertising sales and publishing. Newrick said he was about to start a business newspaper that Rennie could edit in his spare time.

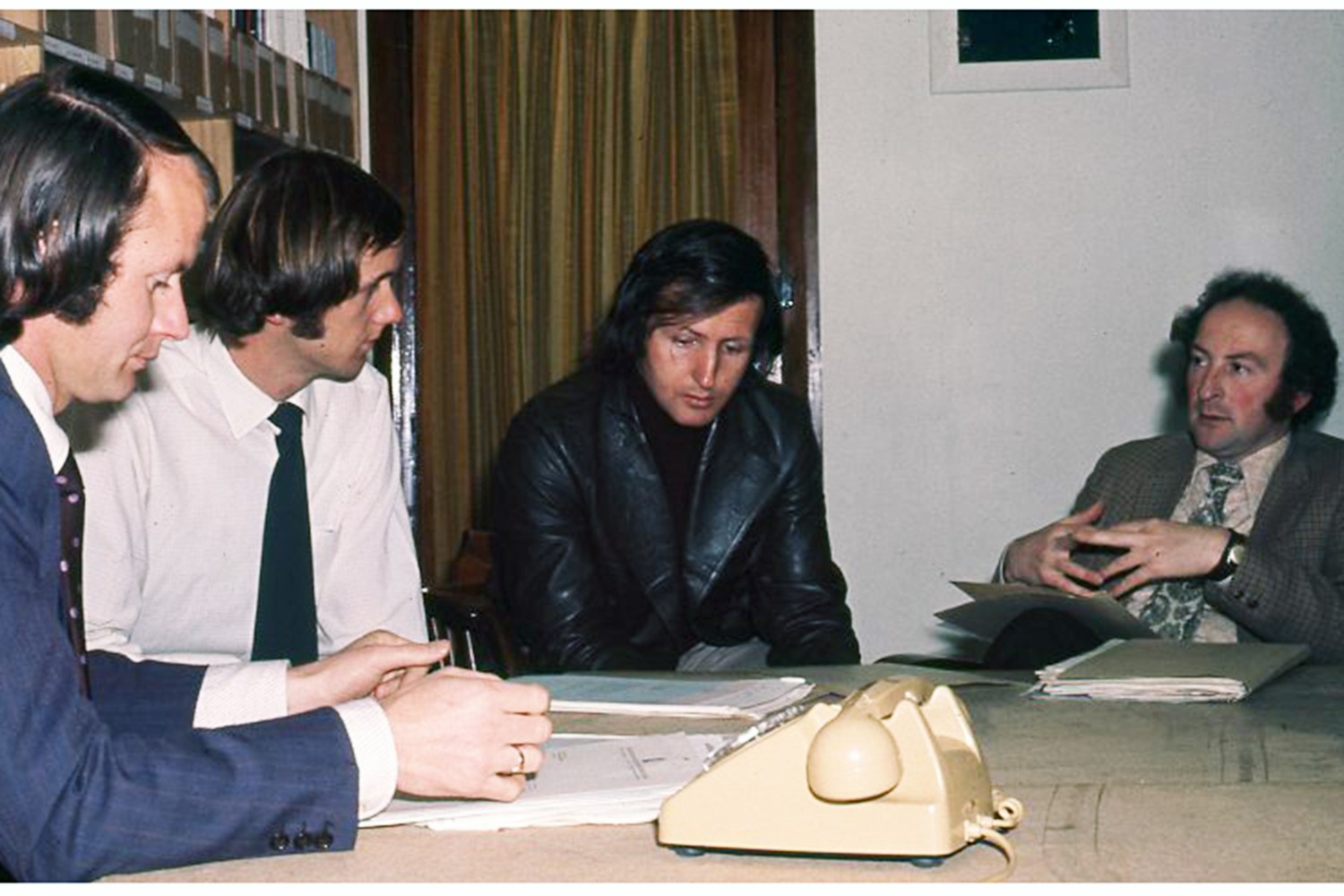

Rennie was dubious the commitment would be a small one, but agreed, bringing in Barrie Saunders, a former co-editor of Salient, and now well-known historian Spiro Zavos. The three of them quickly realised at least Saunders would have to ditch his work at Radio NZ for the thing to get off the ground.

The plan was to publish a fortnightly paper, but the model of business news being proposed was entirely different to what had come before, Rennie says.

“It is almost impossible to exaggerate the extent to which there wasn’t any real business journalism at the time,” he says.

“The nearest thing to it was there were a couple of monthly magazines, one that one way or another covered the economy, and the other the sharemarket, and two or three, shall we say, ‘publications’ where, if you bought an advertisement, you could get an article inserted about what a great company you were.”

Daily papers weren’t interested and didn’t understand business news. But Newrick had had success in doing specialist newsletters in property and mining and realised there was an opportunity and an appetite.

Rennie says Newrick was the most outstanding advertising manager he’s every worked with – both confident of getting advertising, and happy to turn the model of the time on its head.

“He had a complete separation in his mind between editorial independence and advertising content,” says Rennie.

“And, in fact, advertisements came in, in the first few months from advertisers used to the idea that you sent an ad along with a feature article about the wonderful chairman your company had and expected it to be published.”

They were gobsmacked to get their contributions sent back: “They could not believe there was a business publication where the advertisements were sold on the basis of the merit of the audience and they couldn’t control what the content was.”

Newrick's pioneering method was in evidence when the paper wrote a story that offended NZ Forest Products, a client of Ilott Adverting. The NBR founder was summoned to a meeting with Harold Austad, Chairman of Ilotts and at that time probably the most powerful man in advertising, and ‘instructed’ to place a retraction and apology in NBR and that failing to do so would result in NZ Forest Products cancelling its ads - and no more advertising from Ilott Advertising.

Newrick says he explained times had moved on; that the NBR would not be bullied, further adding that if this happened the paper would contact all of Ilott’s clients saying that we no longer recognised the agency, would not pay the traditional 15% commission and would only accept business direct from clients.

"That was at a time when every advertisement counted," says Rennie.

First story

The first issue’s lead story examined which companies were organising to try and get the consideration to run a second television channel, at a time in New Zealand history when one basically either watched one channel or didn’t watch television at all. The story had both business and political ramifications.

Rennie remembers his own first story as being one about an old Wellington company, the management of which had been quietly siphoning up shares that the wider shareholder base did not realise were becoming more and more valuable.

“The company was absolutely outraged about this being reported – it had been a breach of security, leaks, and all the rest. In fact, it was written by reading their annual reports, which ones finds at the Companies Office but, of course, nobody in those days would go to the Companies Office to read that material.”

Rennie also drew on his legal work to inform some of his story choices – things such as various types of syndicate and mortgage finance schemes he’d come across.

“It was a bit of a hodge-podge. Then, of course, when there was a dirty great gap in the paper, I’d have Barrie shouting at me: ‘can’t you write something?’, ” he recalls.

Financial woes

While the new advertising model and crack stories were slowly making an impression on the business establishment, the nascent publication’s books were suffering.

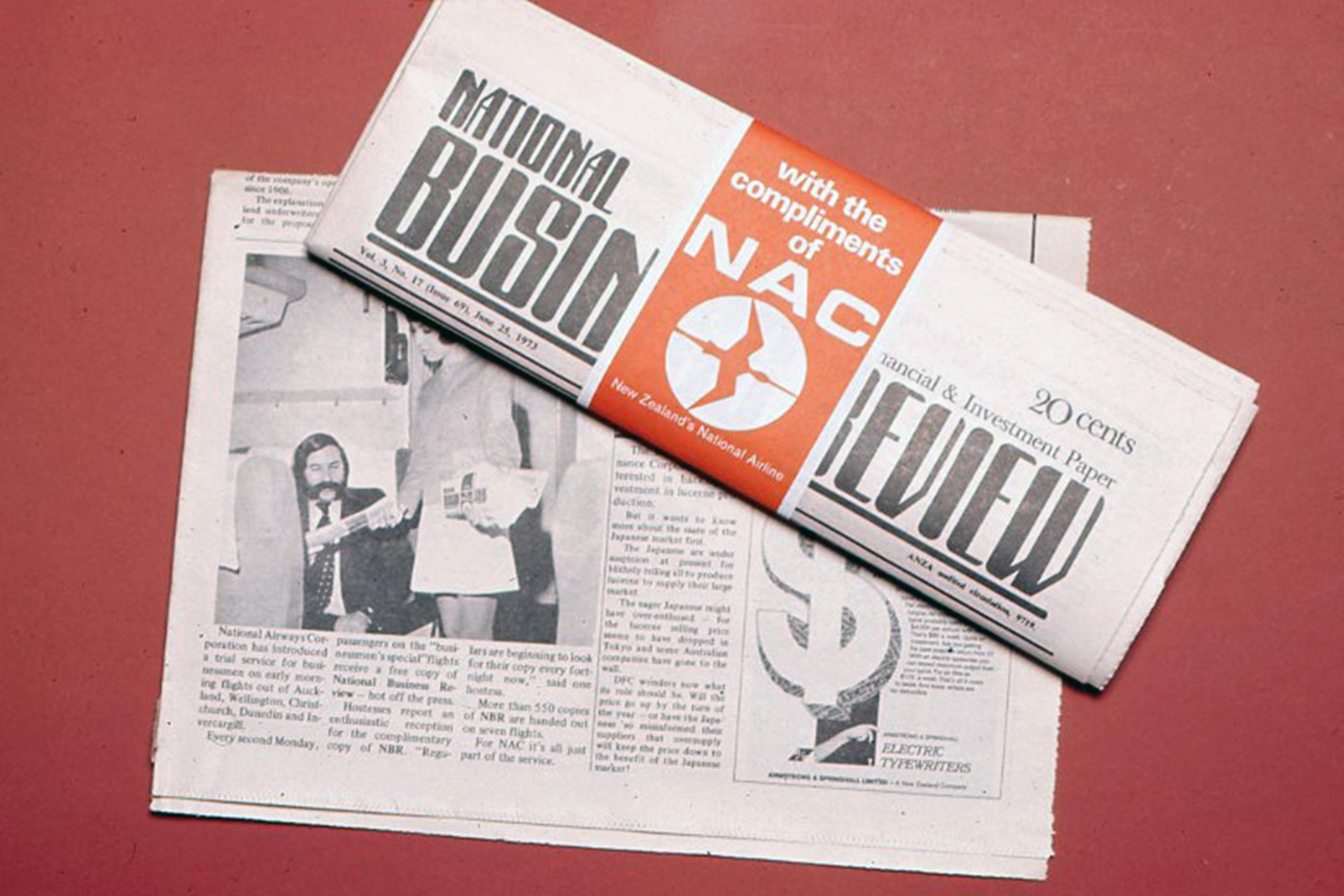

At the end of 1970, just a few months in, the paper had sold a grand total of 900 copies and was almost out of financial puff, but an injection of new blood and investment money saw things improve in 1971. Fourth Estate Publishing was established, new investors including now-South Pacific Pictures head John Barnett chipped in, and Reg Birchfield came in to edit the magazine, a role he held for several years, along with many others.

Rennie remembers the team had weekly board meetings in lunchtimes to try and keep the paper afloat, attended by the ‘financial guy’ who came off working night shift in a bakery and covered with flour.

“He’d turn up with a scrap of paper from the bakery with figures on it saying, ‘this is where we are’ and, by the time we’d found out where we were, if we’d known where we had been, we would have given up! That’s how tight it was.”

One reasonable cost the company was happy to pay was for good quality printing. The early NBR was printed in Nelson by the legendary Rex Lucas, manager of the Evening Mail from 1949 to 1977 and the man who was a pioneer in bringing web offset printing to the country.

“We were lucky, because in 1970 when the paper started, Rex was able to deliver a really first-class tabloid – beautifully printed, working to very late deadlines; it wasn’t a print job, it was a paper, and that’s what he cared about.

“Although he had a couple of occasions when we got buried in defamation writs and he lost his nerve and we had to go to Whanganui to get it printed, he carried on through the 1970s and he was a major contributor to [our] existence.”

Lucas died in 1977 and his sons took over the business.

The Muldoon years

The major centrepage feature of the first issue of the NBR was a lengthy interview with the then-leader of opposition, Robert Muldoon.

At first the relationship between NBR and Muldoon, “rambled along quite readily” but, as the paper gained in influence, he started to dislike it, calling it at one point “the Sunday News of financial journalism”.

NBR aimed at all times to be politically independent – and still does. Rennie himself had been moderately active in the National Party until 1974 but left so as to maintain the paper’s neutral stance. By 1975, most other publications were saying Labour would win the election but NBR editor Birchfield called it correctly for Muldoon, one of the few who did.

Despite the fact National was and remains the favourite party of business, the “financial environment Muldoon presided over lacked any rational sense – it was very difficult to operate in,” Rennie says. At one point, the NBR could only put up the prices on its very popular NZ Business Who’s Who to cover costs if it got the publication printed in Australia, such was the level of inflexible price control in operation on this side of the Tasman.

The NBR was not afraid to call Muldoon’s various policies irrational.

“Oh no, we went in boots and all,” Rennie says.

“In the first few years, up until about 1976, we were sufficiently small that we could be brushed off for being irrelevant – it was after that, from memory, when we got to an audited circulation of a bit of 5000 about 1975, all of a sudden we were a significant influence and that was the stage at which the likes of Muldoon would pay attention to us.”

So much so that Muldoon refused to be interviewed by NBR’s Colin James in the late 1970s: “he wanted to be interviewed by someone he would have less difficulty dealing with”.

Part of something bigger

Ten years in and many of those who had begun the paper as fresh-faced young men were family men with other careers and mortgages, and some wanted to get their cash out.

Being bought by listed company Computer Consultants Ltd in 1980 would allow some of these people to cash up.

“By 1980, we had probably around eight people who had ended up putting in money with mortgages on our houses,” Rennie remembers.

“We never quite knew we wouldn’t wake up one morning to find the company had been wiped out by a massive defamation writ or, if one day you’d wake up and find that one of the major press companies (at that stage Wilson & Horton, NZ News, and Wellington Newspapers (INL))might have started a business paper; they would have run us out of business with the morning tea money.”

The other consideration was that the NBR had some significant media projects in the pipeline – but no capital to run them. The largest was a type of internet pre-cursor called Viewdata, which would use telephone lines to link to a central database. It was a project involving many disparate companies and CCL, it was envisaged, would provide both capital and know-how.

The plan did not eventuate.

“At the end of 1980–1981, which was when we should have really been able to turn that to account, unexpectedly to us, CCL absolutely fell to bits, it turned in a disastrous result at the end of 1981 and far from CCL funding us, we were funding CCL – to the extent that we could.”

CCL found its feet again when it attracted an investor, a Rotorua-based newspaper publisher called UPP, which ran Rotorua, Whanganui, and Levin dailies. That got CCL back on its feet, but also demonstrated there wasn’t really any synergy between a newspaper company and a computer company, Rennie says.

Fairfax

In 1983, a Fairfax representative crossed the ditch with the idea to establish a New Zealand version of the Australian Financial Review (AFR). He’d approached Wilson & Horton first, but they were not interested. His next stop was NBR in Wellington. “He thought you could print it in Auckland and put it on a truck and have it in Wellington in time to sell it in the morning – shame he had no idea what driving from Auckland to Wellington looked like,” Rennie remarks.

“He also rather missed the point that New Zealand was two hours ahead of Australia so the deadlines didn’t work in terms of what would have been facsimile transmission, except that facsimile transmission barely existed in those days. They were actually going to deal with it ... by air freighting all the early pages as letter press finals for the printing works and sending the late copy by telecoms.”

Despite the unrealistic ideas, Fairfax took a half stake in NBR and that pleased CCL; not only was the company an expert business publisher already but big enough that local companies would not take it on. The Fairfax and CCL joint ownership went along “very harmoniously and productively for a year or two” Rennie says.

But publicly-listed Fairfax Australia still wanted to have a financial daily in New Zealand, which was beyond the appetite of CCL, who eventually sold their share to Fairfax in 1985.

The plan all along – a detailed, structured plan that envisaged seven-figure-losses coming to break-even over five years – was to move to daily publication, which the paper did in 1987, before two factors upset the apple cart: the stock market crash of 1987, and the involvement of ‘young Warwick’ Fairfax, otherwise known by Australian media as “the man who wouldn’t wait”.

Twenty-six-year-old Warwick was the son of Sir Warwick Fairfax, the descendent of John Fairfax who established Australia’s oldest media empire in 1841. In 1987, after the death of his father, Warwick and what Rennie describes as “a bunch of cowboys in Western Australia” put together a deal to buy up family shares and privatise the company.

The takeover was handled in such a cack-handed fashion that before acquiring all the shares, their value slumped to below Warwick’s offer price, leading the trustees of the company to sell to the young man or risk losing their investment – but also ensuring Warwick spent quadruple the company’s value to gain control and plunged himself into enormous levels of debt.

He was quickly forced to sell off parts of the empire and, in corporate raider Robert Holmes à Court’s Bell Group, found a willing buyer for the AFR, the Times on Sunday and some broadcasting assets.

Then the stock market crash hit, and NBR was suddenly plunged into limbo-land, according to Rennie.

“I had the interesting experience, from late 1987 through to March 1988, of being chair of a company that nobody knew who owned – literally – and it was losing money by the week,” he says.

“The legal advice to Holmes à Court was ‘don’t exercise any power over it, because that will show you have bought it’, and the legal advice to Fairfax was ‘don’t exercise any control over it because that will show you haven’t sold it’.”

The back and forth proved so impossible for Rennie that he made a decision at the beginning of 1988: he’d leave the NBR once the ownership issue was resolved, and he’d get out of media altogether and concentrate on the law shortly thereafter.

The upshot was that Fairfax sold first an interest to Liberty Press, Barry Colman’s group, and then bought the company back, or its main assets in any case – NBR itself and Personal Investor magazine, the precursor to the NBR Rich List and one with more than 30,000 in sales an issue.

Colman then set up a rival, The Examiner, which unnerved Fairfax as it was still struggling to make its daily NBR a consistently viable proposition and didn’t want competition. It decided to exit New Zealand. There was, Rennie says, significant interest in the company by then but Colman triumphed in 1991, buying the publications and assets for an undisclosed sum that Rennie says he does not know specifically but was “several millions”.

Final thoughts

Rennie says there is a lot that could be said about NBR’s influences and the changes it bought to the world of both business and journalism in those early years, but one example illustrates what he says is the paper’s enduring legacy.

In 1976 in New Zealand, the privately held finance company Securitibank collapsed, losing many investors all their money.

“It was an awful mess and, frankly, people should have been prosecuted for fraud in relation to it – but that didn’t happen. I don’t, to this day, quite know why, although I have often wondered if it was the ‘old boys network’ at play,” Rennie says.

Its collapse led the then-National government to pass the Securities Act 1978, ensuring people who invested had a registered prospectus with full and proper disclosure, and led to further legislation around things such as anti-insider trading law.

“It was intended to be a self-disciplining act. Instead of an external regulator coming in and saying ‘do this and that’, it was intended that the economic penalties for not complying were so severe that a business would comply – but the question was, how would people know?”

Rennie says officials told him that with the NBR in place, regulators believed company wrong-doings would be exposed and companies would not try and get away with it.

“Now that would never have happened in 1970 or 71. If we had done it then, no-one would have noticed,” Rennie says.

"But that’s how dramatic it was; by 1976, the securities regime was actually being fine-tuned on the assumption that there would now be enough information out in the marketplace, that the marketplace would deal with these things, and that was a moderately successful device.”

That was one thing Rennie believes is remarkable – and the other is the role NBR played in sending trained business journalists out into the wider media world.

“There were an awful lot of us in the 1960s. I don’t want to claim a particular personal credit – a contribution by all means, including for 18 years trying to make sure defamation claims didn’t exist or, if they did exist, didn’t succeed. I always felt that was my biggest contribution.

“But also there were a lot in the 1960s who wanted to get out into the media – but the media wasn’t out there to get into.”

Rennie says he remembers finding a young keen journalist who had just left the provincial dailies in his office sobbing, and asked him what the problem was.

“He says: ‘I have just been down to the Evening Post to ask for a job and they told me I’ll never get one because I am over qualified!’

“So the big thing for most of this, is that we managed to push through and create careers for a lot of really able people ... and many of those people are still around the media today.”

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.