World’s most capable country never boasts

OPINION: An Englishman explains how they do it and get little credit.

OPINION: An Englishman explains how they do it and get little credit.

Benchmarking exercises are a popular and reliable way of measuring success. A large number of international organisations from the UN down perform this task. So, too, do think tanks, lobby groups, and businesses.

Few activities are left out of the mix, from human development, economic, political and religious freedom, to happiness, wealth, corruption, and tax environments.

Annual surveys I carried out for the NBR in recent years showed New Zealand was among the best countries in which to be born, educated, start a business, and live in safety with easy access to healthcare, income security, and a comfortable retirement. The Economist once ranked New Zealand as the best country in the world to start your life, given the opportunities it offered for a lifetime, including the ability to live in and work elsewhere, as an estimated million Kiwis already do.

New Zealand yields to no country in freedom to do business. It has topped the World Bank’s Doing Business report since 2016. Sadly, due to an external review that found bank staff were being pressured to massage data in favour of China, that report was canned in September.

Doing Business assessed the regulatory environment in 190 countries across 11 topics, including starting a business, getting electricity, paying taxes, and enforcing contracts. Critics pointed to data showing a gap between hypothetical regulations and the realities reported by businesses. The survey also did little to capture government activities that strengthened business, such as skills training and the state of infrastructure.

These discrepancies did not show up in rich countries but they did in poorer ones with large informal economies, regulations were ignored, and corruption was endemic. Count the loss of Doing Business as another win to the likes of China and Russia, which subvert the organisations formed after World War II to maintain peace and spread freedom to prosper under democratic rules.

Success harder

The loss of Doing Business makes it harder for New Zealand to succeed in other world scorecard exercises that emphasise competitiveness, innovation, and wealth due to lack of scale and access to large markets. One example is the Legatum Institute’s Prosperity Index, backed by expat Kiwi billionaire Christopher Chandler.

New Zealand topped the rankings for most of the index’s 15 years but in 2020 had dropped to seventh out of 167 countries. The index now covers a much wider range of topics and countries. On 13 measures, New Zealand was ranked below 100 on mainly health issues such as obesity and addiction.

The same group of countries dominate most indices, no matter what they measure. These are the rich countries of northern Europe and North America, with Australia, Japan, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates as geographical outliers. Rankings are particularly high among the Nordic countries – home to Michael Booth’s The Almost Nearly Perfect People (2014) – and their large near-neighbours, the UK, France, and Germany.

Former New Statesman editor John Kampfner has challenged Booth’s culturally-oriented account with Why the Germans Do it Better, a post-Brexit analysis of Europe’s largest and most prosperous economy.

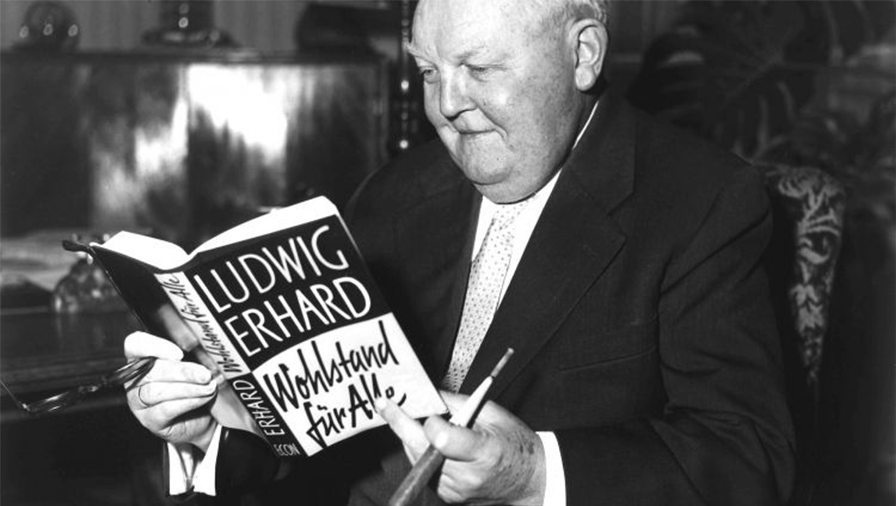

‘Miracle’ economy

His near-300 page study covers Germany’s post-war “miracle”, based on neoliberal economics, and a generous welfare state based on cultural values that reward diligence, hard work, and inclusiveness. Other qualities he admires, from his experience as a foreign correspondent in East Germany for the Daily Telegraph, are the ability to self-analyse success and failure, lack of bragging, respect for rules, punctuality, and commitment to high cultural values.

After surviving two world wars mainly of their own making in the 20th century, Germans have learned from the extremes of fascism and (in the east) communism, enjoyed political stability under an MMP electoral system, and offered a new home to millions of displaced people from places of conflict and poverty.

Since unification in 1990, when the communist regime was officially absorbed, Germans have avoided the worst of recent crises, including extreme nationalism and the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Germans still cannot countenance the suggestion that, on many accounts, that they do it better. They are alarmed by the very idea that they could possibly teach anyone a lesson,” Kampfner says.

Excellent value

It’s not a judgment many would disagree with from personal experience or the historical record. Germany is excellent value for the foreign tourist, regardless of their language, and does not hide its recent history. This understanding of its past, and its many museums for that matter, contrasts with that of, say, Austria, Spain, Italy, Russia, and Japan.

The way Germans do business with each other and the outside world is widely admired. They may be too respectful of rules for many tastes (Sunday shopping is still absent), but they also tolerate a wide variety of views while still displaying strong social cohesion.

Of course, that is not to say Germans are content and complacent. In fact, Kampfner notes they have the same anxieties and apprehension of many Europeans toward the state of democracy, alarmism about the climate, and fear of anything nuclear, even in the face of energy shortages.

Interestingly, much of this has emerged with the pending departure of Angela Merkel, the Mutti (mother) of the nation, and her unshakeable demeanour. Kampfner devotes an entire chapter to how this East German-raised physicist ran the country for the past 16 years, often in a coalition with the main centrist opposition party.

Lacking charisma

“You can’t solve the tasks [of government] with charisma,” she told an interviewer for Vanity Fair, and disdained Barack Obama for that reason. She equally despised Donald Trump for his vulgarity. A new biography by Kati Marton describes her approach as “cautious, low-key, self-effacing, analytical, patient, attentive and, for the most part, incremental.”

That didn’t always lead to sound decisions, or popularity, but it has led to a political vacuum. The election in September didn’t break the traditional impasse of MMP, and Germany can no longer depend on the tripartite setup that worked well for the first 50 years.

Merkel’s Christian Democrats failed to edge out the Social Democrats, and neither gained enough support for a continuation of the former coalition, thanks to gains by the Free Democrats and the Greens. Other extreme parties also have a foothold in the parliament. She remains as caretaker chancellor until a new government is formed.

This political uncertainty is unlikely to undermine Germany’s economic future, which is still based on immigration-fuelled growth and the strength of its Mittelstand, the hundreds of thousands of SMEs that are its industrial backbone. They employ three-quarters of the workforce, and produce 80% of the GDP.

German firms make up half of the 2700 globally-active companies that dominate markets in a single product. No other European country has these, with the rest coming from the US, China and Japan.

The target readers for this book are the British, who are struggling to survive Brexit. New Zealanders will benefit from the German experience in learning from the past and a dogged commitment to democratic values that integrate rather than divide.

Why the Germans Do it Better, by John Kampfner (Atlantic Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.