Worlds in collision: A history of culture

How the arts and humanities preserve the past for future generations.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

How the arts and humanities preserve the past for future generations.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

The word culture has many meanings; so much so that in the current parlance of public debate it is associated with ‘wars’ and being ‘cancelled’.

A quote from a 1933 play by German Nazi SS officer Hanns Johst is a favourite for those who disparage fascists and philistines: “Whenever I hear the word ‘culture’ I release the safety on my Browning [pistol].” Like many quotes, it has been corrupted in translation to the snappier “… I reach for my gun”.

For offenders, a ‘cultural report’ in a New Zealand court often means a lesser sentence. Highbrow critics, such as The Australian’s writer on fine arts, Christopher Allen, lament “the moribund state of popular culture in an age of mass consumerism”.

He has a warning for anyone devoted to the humanities: “Those who live in a world of literacy, of art, literature, music, and ideas can easily lose touch with what goes on in the minds of people who never read books, who know nothing about history, who never look at art, or listen to any but commercial music.

“Such people exist in a post-cultural world, bereft of the moral and symbolic systems that give meaning and value and direction to our experience, and of the traditions of representation and reflection that allow us to see our lives in perspective. With no living culture of their own, they are not in a position to ponder the values and the different viewpoints of other cultures.”

For some, those scathing words might automatically deny Allen entry to New Zealand, or at least be drawn to the attention of the proposed mega media regulator. But they would likely be applauded by Germany-born Martin Puchner – Byron, and Anita Wien Professor of Drama, English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University.

Harvard Professor Martin Puchner.

The latest of his many books is Culture: A New World History and he works in a sector we are told is fast disappearing. (University of Auckland Emeritus Professor Michael Neill, brother of Sam, said this week that his English department had at least 30 full-time equivalent staff in 2000 but today only four.)

Puchner doesn’t see an existential threat but does consider culture is caught between two conflicting views. One is inward-looking and proprietorial; it wants to protect national traditions and prevent appropriation. The other is outward-looking, always seeking for encounters with other cultures – and borrow from them if necessary.

He sides with the latter: “… [I]f we want to restrict exploitative tourism, avoid disrespectful use of other cultures, and protect embattled traditions, we need to find a different language than that of property and ownership, one more in keeping with how culture actually works.”

His book comprises 15 chapters about people or events that have shaped the history of world culture; people such as the Chinese traveller Xuanzang, who brought back Buddhist manuscripts from India, and the Arab and Persian scholars who translated Greek philosophy for posterity.

This form of intellectual history depends on how cultures have been preserved, or in many cases, how they have disappeared. It’s a tale of storage, loss, and recovery. The locations include the ancient pyramids of Egypt and Greek theatres, Buddhist, and Christian monasteries, Italian Renaissance studiolo (elaborate private libraries), and 18th century Parisian salons for learned conversation.

The ancient theatre of Epidaurus in Greece is still in use today.

All are examples of cultural “traffic” – India borrowing from Persia, Romans from the Greeks, Chinese from the Buddhists, and Japan from China. For Puchner, culture “is a vast recycling project in which small fragments from the past are retrieved to generate new and surprising ways” to view history.

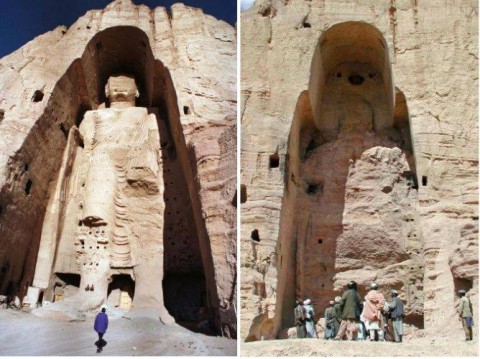

One of the Buddhist statues at Bamiyan pictured in 1997 and in 2001 after its destruction.

This didn’t happen easily. The European archaeologists of the 19th century who literally put the shovel to Egypt and Greece did not ask permission when they found buried treasures and took them back for study in the museums of London, Paris, and Berlin.

“When seen in hindsight, much of culture involves interruption, misunderstanding, and misreading, borrowing and theft, as the past is dug up, taken and used for new purposes,” Puchner notes of practices that have occurred throughout the 5000 years since the first forms of writing.

Take the Buddhist statues of Bamiyan in today’s Afghanistan. This was where the New Zealand Defence Force had its base. News reports in the past week showed little of that contribution remained thanks to the Taliban, who in 2001 also destroyed the statues. These were first described in detail by the previously mentioned Chinese traveller Xuanzang, whose Record of Western Regions, published in the seventh century, is a classic example of cultural mobility.

While Buddhism later declined in India, giving way to Hinduism, its introduction to China provided a contrast to the prevailing Confucian culture. Buddhism spread east to Korea and Japan two centuries later thanks to a Japanese monk and his journal Ennin’s Diary (not translated into English until 1955).

The Chinese emperor of the time, Wuzong, turned against Buddhism in the Tang persecution, destroying its temples, but Ennin took his experiences back to Japan, where a new script called kana had made writing easier.

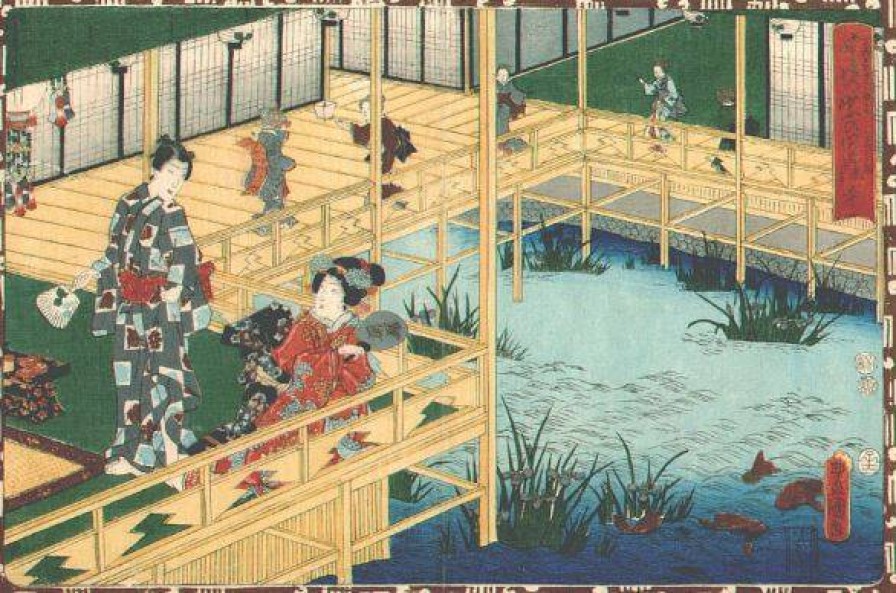

Japanese woodblock illustration of The Tale of Genji, written in the 11th century.

In the 11th century, a courtier and lady-in-waiting, Murasaki Shikibu, produced what Puchner calls the first great world novel, The Tale of Genji, which was widely acclaimed when translated into modern Japanese and English in the early 20th century.

The influence of Japanese culture on Western art and modernist literature is the subject of another chapter that describes how 19th century American historian Ernest Fenollosa and his wife Mary McNeill introduced new perspectives to poets Ezra Pound and WB Yeats, and the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht.

Cultural events outside of Asia and Europe are not ignored. The background to Kebra Nagast, a 14th century account of the Hebrew Bible’s King Solomon, the Queen of Sheba, and how the Ark of the Covenant arrived in Ethiopia, is a fascinating read about this African variant of Christianity.

This Portuguese epic poem was written in 16th century.

The destructive forces of colonialism are explored in chapters on the Aztec civilisation and the “floating city” of Tenochtitlan when confronted by Spanish invaders, and of Wole Soyinka’s contribution to post-imperial Nigeria. In examples of cultural transfers, the Greek philosopher Plato rewrote his country’s history to reflect his views, while the Roman poet Virgil did the same for Rome.

Baghdad in the ninth century, under Caliph Al Ma’mun, became the world’s Storehouse of Wisdom as Islamic scholars used the invention of paper in China to preserve knowledge of astronomy, medicine, and mathematics as well as Greek philosophy that had faded in Europe.

European culture revived in the libraries created by Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne and Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen; the exploits of 16th century Portuguese explorers in The Lusiards, an epic poem by Luis Vaz de Camões; and most recently in Norway’s Future Library project, which aims to collect an original work by a literary figure every year from 2014 to 2114 on condition the writings remain secret until their unveiling in the next century.

Puchner says all of the historical texts he quotes from lasted to the present day by beating overwhelming odds, both from natural disasters or deliberate sabotage. “They survived despite the fact that they were at odds with the societies by which they were found and by which they were preserved.” Generally, speaking, they were not the purists, who tend to shut down (or “cancel”) alternative ideas, limit possibilities, and police exercises in cultural fusion.

In a final plea, Puchner notes that only 8% of the incoming class to Harvard in 2021 expressed a primary interest in the arts and humanities, thus confirming art critic Christopher Allen and Professor Neill’s worst fears. It can only be hoped this book, with its wealth of sources for further reading as well as illustrations, can help redress the world’s problems that can’t be solved by technology alone.

Culture: A new world history, by Martin Puchner (Ithaka Press/Bonnier Books UK).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.