World in turmoil – the dangers to New Zealand’s security

Threats include terrorism, climate change, cyber-attacks, and weak defence force.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Threats include terrorism, climate change, cyber-attacks, and weak defence force.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

If you’re looking for a reliable source to the coming year, a good place to start is The World Ahead 2024, the 38th edition of The Economist’s annual predictive guide. It runs to 90 pages and was available to digital subscribers with last week’s regular edition.

The Economist’s correspondents, including named expert commentators, never beat about the bush. The heading on the lead editorial is: “Donald Trump poses the biggest danger to the world in 2024.” The US presidential election won’t happen until early November, so there is breathing space as well as time for his political fortunes to be reversed.

Previously, The Economist has spelled out that a Trump victory won’t result in a chaotic administration like the first. Planning for a second term has been months in the works. It will be bent on retribution, so the main impact will be on America itself. “Mr Trump will wage war on any institution that stands in his way,” The Economist says in its plain, blunt prose.

The world will suffer, too, with the main beneficiaries being the new “axis of evil” – China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. But don’t expect a rerun of the first term, in which Trump scored some major wins: arming Ukraine ahead of the Russian invasion, scaring Europe into greater defence preparedness, and pursuing a peace deal between Israel and many of its Arab neighbours.

Donald Trump.

Since Trump lost power in 2021, the world has changed dramatically and so will Trump’s responses. He is likely to abandon Europe and pull the US out of backing Ukraine, though not Israel. He may be open to a deal giving Taiwan to Chinese President Xi Jinping, forcing US allies such as South Korea and Japan to acquire nuclear weapons. As for global action on climate change, that will slow without American support.

The Economist gives a rundown on the “concatenation of crises” afflicting the globe, while noting this is nothing new. It cites past examples, such as the invasion of Hungary and the Suez war in 1956; conflicts in Lebanon and Taiwan in 1958; the Chinese and Russian invasions of Vietnam and Afghanistan, respectively, and the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1978-79; as well as a renewed conflict in Kashmir and the Nato bombing of Serbia in 1999.

Co-editor Wil Hoverd.

As 2024 approaches, The Economist sees the large powers as more polarised than before. More countries have ganged up against America and its allies over today’s crises. This has brought more countries – including New Zealand, Australia, Japan, and South Korea – closer to a reinvigorated Nato, while a “multipolar” world has boosted secondary powers, such as Turkey and India.

Quoting several experts, The Economist says this has created a “sense of disorder” that has crippled the World Trade Organisation and the UN, creating “a kind of anarchy” in international relations. Not anarchy in the strict sense, “but rather the absence of a central organising principle or hegemon”.

The last word, used by a former Indian national security adviser, has Marxist origins and crops up in the introduction to a new volume of essays put together by Associate Professor William (Wil) Hoverd, director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at Massey University. This is Hoverd’s second book on national security issues. The first was published in 2017 with two other co-editors.

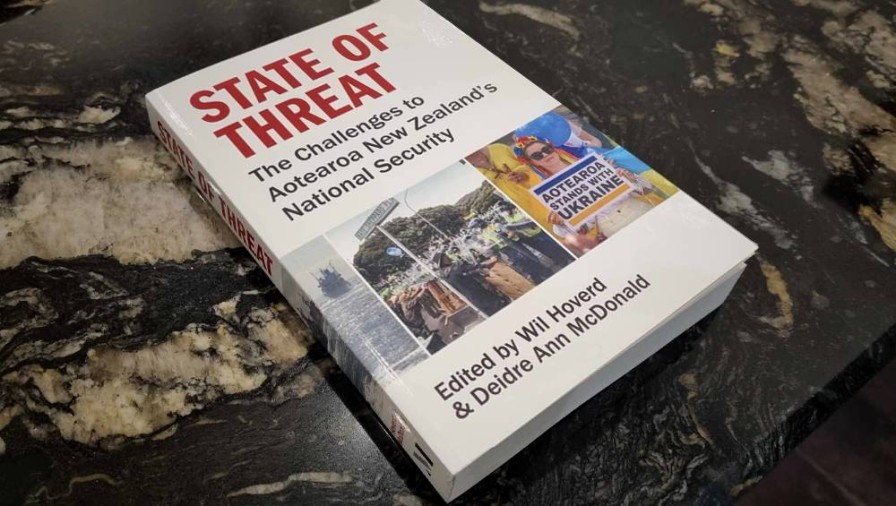

The latest, State of Threat, has a catchier title and a new co-editor, Deirdre Ann McDonald. Its publication coincides with that of Abolishing the Military, reviewed here last week, and takes a much different stance from the University of Otago’s pacifist academics. The Massey centre is as close as you can get to a defence think tank, though it starts out by saying debate on national security issues should not be confined to an elite.

Co-editor Deirdre Ann McDonald.

This group, as you might expect from a tertiary institution, have a “hegemonic monopoly” over this debate and offer “prioritised discourses [that] contain the inherent bias associated with their hegemony (wealth, education, whiteness, heteronormativity, and maleness)”. In plain language, this is saying there is a lack of input from all the ‘victim’ groups in neo-Marxist or postmodernist critical theory: women, minority races, gays, non-Christians, etc.

In global terms, this is nonsense, as the quote from an Indian source above shows. National security is an issue for all countries, none of which are unaffected by the four main trends in the “new world disorder”, that is, climate change, technological advances, globalisation, and the rising of tide nationalism and populism.

All are examined in State of Threat, though its 17 chapters cover a much wider ground than the international issues discussed so far. They are equally grouped into four sectors: offshore threats and opportunities; intelligence and domestic security; governance and extremism; and future security issues.

In the first group, Dr Reuben Steff (University of Waikato) describes the “shatterbelt” of the South Pacific as open to both internal division and outside intervention. He poses three options for New Zealand, with armed neutrality as the least likely option.

Dr Stephen Hoadley.

Associate Professor Steve Hoadley (University of Auckland) – the best known of the contributors – takes an ‘if it’s not broken, don’t fix it’ approach to the maritime environment. Unlike other contributors, who call for a more precautionary approach, Hoadley says the lack of serious incidents indicates this is well managed. He points out that if something major does occur, the delayed response often achieves the best outcome.

This commonsense is lacking in the chapters on the Covid-19 experience and a study of defence personnel recruitment and morale. It argues the ‘neoliberal’ freedom of choice benefits self-improvement and marketable skills, and should be replaced by secure lifelong employment in public service.

The importance of submarine cables, the fight against the illegal drug trade, biosecurity threats, and fears of bias in artificial intelligence (“dominated by white technically educated males” – no mention of Indians and Chinese) cover the second section on intelligence and domestic security.

The issues of governance and extremism are more provocative, with intelligence gathering singled out as needing greater ‘democratic’ control – usually code for easing up on the usual suspects who pose a threat to bourgeois society.

Sir John Key.

Hoverd examines the arcane topic of how the prime minister has overall responsibility for national security but, since Sir John Key’s time, has devolved responsibility for the two main government intelligence agencies to a cabinet minister.

Dr John Battersby (Massey University) – an authority with practical experience in police work – thinks the official rating of the threat from overseas terrorism is too low, leading to complacency. Evidence would suggest more people fear the real domestic threats from the growth of motorcycle gangs and violent crime than acts of terrorism.

Likewise, the final contribution in this section, on right-wing extremist women, says more about the interests of researchers than security threats to economic and property interests.

Massey University’s Professor Rouben Azizian.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, its exorbitant costs in munitions, and flouting of international norms, dominate the final group of essays, thanks to contributions from overseas authors, including two Polish scholars. They urge a greater involvement by New Zealand in protecting the ‘democratic’ world and its role as a ‘good world citizen’.

Cryptocurrencies are described as a ‘double-edged sword’ that has both advantages to a small economy as well as making it easier to transact international crime.

The same term is applied by Professor Rouben Azizian (Massey University) to the most common cause of warfare since 1945. The opposing forces of self-determination and resistance to secession have been responsible for 70% of conflicts since 1945. Since the early 1990s, that proportion has risen to 90%.

In by far the best contribution, Azizian points to how these forces pose continuing threats in places such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and West Papua, as well as Taiwan. He quotes from a recent Atlantic Council survey of security experts. Some 40% expect the Russian Federation to break up and half of them expect it to be a failed state inside a decade.

Strong arguments against this say the federation, unlike the Soviet Union, does not make it easy to secede. The Economist says the prospect of a Trump victory would encourage President Putin to keep the war in Ukraine going as long as possible. The prospect of less turmoil does not look promising.

State of Threat: The challenges to Aotearoa New Zealand’s National Security, edited by Wil Hoverd and Deidre Ann McDonald (Massey University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.