What’s in a name? Blair in Burma

Novelist Paul Theroux explores the connection between two famous changes.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Novelist Paul Theroux explores the connection between two famous changes.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

The pros and cons of changing names of countries or organisations do not provide a clear case one way or the other. When I asked Microsoft Bing, the response was based on some Harvard Business Review research.

With companies, a change could represent “a sign of innovation, adaptability, or growth potential” in market perception, or a desire to “shed a negative image” and enhance its brand or image. A local example of both would be the change from Telecom to Spark, which occurred after the network operation was spun off as Chorus.

Mostly, though, such changes are more likely driven by legal requirements, such as international companies Shell and Vodafone selling out their New Zealand interests. Thereafter, the subsequent success or otherwise is solely due to performance.

When it comes to countries, the outcome is less certain. The fact that it occurs only rarely is evidence that the confusion and costs aren’t worth it.

Forced name changes due to legal or other disputes are more acceptable. Recent examples include The Netherlands replacing the two provinces of Holland (2020); North Macedonia (after pressure from Greece in 2019); and Czechia, a simplification of the Czech Republic after the split of Czechoslovakia (1992).

The most egregious examples of name changes are due to post-colonial disasters: Burma to Myanmar in 1989 after the military junta suppressed a popular uprising; and South Rhodesia to Zimbabwe, the worst performing of the British Empire’s African colonies. Incidentally, New Zealand is at the top of the Bing list of countries potentially changing their names, followed by India to Bharat.

Paul Theroux at Chicago book launch in 2008.

Photo: Ramnarasimhan/Wikimedia Commons.

Name changes feature in American writer Paul Theroux’s latest novel, Burma Sahib, an elaborately imagined version of Eric Blair’s five years in the Indian Imperial Police from 1922 to 1927. A few years after his return to England, Blair became George Orwell, probably the century’s best-known pseudonym before David Cornwell became John Le Carré.

With the benefit of hindsight, Theroux puts Blair’s cynicism toward the British Empire into a context where the colonial experience was preferable to what came later. Blair is depicted as despising almost everyone he associated with as a senior police officer at various posts around Burma, then a province of the Indian Raj.

Eric Blair in the Eton College Yearbook (1921).

Photo: Eton Museum

One pukka sahib (European white man) advised him soon after his arrival: “A hundred years from now there will be disorder in Burma, and alarm and despondency.” No truer word can be said about a country that today ranks at the bottom of the heap, as its military rulers continue to wage war against its population. The Economist recently reported they also protect Chinese-backed gangs that are “smuggling drugs, gems, timber, and people”.

Blair was born in Motihari (Bihar), Bengal, in 1903. His father spent 40 years in the Indian Civil Service as a quality controller of opium shipped to China until that activity ceased in 1916.

Theroux shares Blair’s view about the quality of men serving the empire: “It seemed the pukka sahib was often a bully and was elevated so far above the native that he had no clear idea of the reality of Burmese life.”

After leaving Eton College, Blair was convinced the British Empire was a “racket” and a con trick. His decision to leave England was to learn more about it rather than go to the University of Oxford like his peers.

Undoubtedly, the well-travelled, 80-ish Theroux (19 travel books and 33 novels) adds much local knowledge, including the languages, to his account of Blair, who at just 19 was in charge of native police recruited from throughout Raj to impose control over a restless and rebellious population.

Criminal activity was rife, thanks to armed bandits known as Dacoits; dowry killings were also common. Buddhist monks were particularly active in opposing colonial rule.

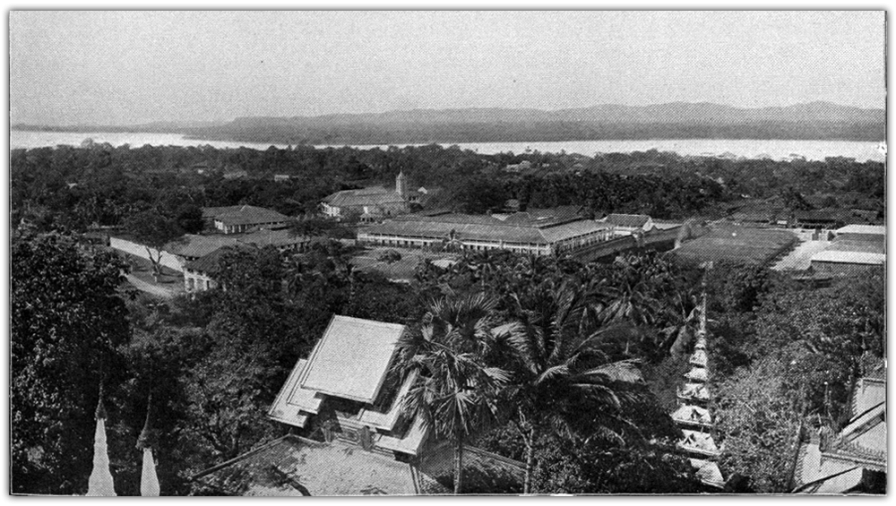

Ancient Burmese capital of Moulmein in 1910.

Blair had connections to Burma as his mother’s French family lived at the port city of Moulmein (now Mawlamyine), the ancient capital of Burma. Despite this chaotic environment, Blair soon settled into a way of life that offered the solace of live-in native women as housekeepers.

They educated the young Blair in ways that could not be matched by studying Shakespeare. Blair also had a deep and adulterous relationship with the memsahib (European white wife) of one of his superiors. She was in her late 20s and they shared a mutual interest in the free-love novels of DH Lawrence. To avoid prying eyes, she disguised herself as a syce (horse groom) on her night-time trysts.

As Orwell, Blair described his experiences in his first published novel, Burmese Days (1934). It was an unflattering portrait that exposed both “indigenous corruption and imperial bigotry,” he later wrote in an article.

At the time, Burma was the wealthiest part the Raj, thanks to its rich supplies of teak, oil, precious minerals, rice, and cotton. The racially structured society produced opportunities for educated locals that would not have been possible without colonisation.

The first (US) edition in 1934.

Burmese Days was initially published in the United States, as it was considered defamatory in the UK, where it appeared a year later. Most of the characters were based on identifiable people. Versions of them return in Theroux’s retelling.

Comparisons have been made with EM Forster’s more positive view of colonisation in A Passage to India (1924), which Blair dismisses: “He only saw surfaces, he had no idea what lay beneath” the brutality at the centre of the Empire.

The most memorable episodes in Burma Sahib are based on two of Orwell’s best essays, ‘The Hanging’ (1931, published under his original name) and ‘Shooting an Elephant’ (1936). The former is refashioned by Theroux as the outcome of a dowry killing where the wrong culprit is executed. In the other, unintended consequences undermine Blair’s authority and lead to his demotion for a destroying a valuable creature worth much more than a native man’s life.

Blair left Burma in 1927 after his five-year posting and, due to ill health, never returned. His biographers have generally played down the impact of his colonial experience. Gordon Bowker suggested the young Blair wanted to leave his “demons” in England and explore his “dark side”.

Others, such as John Sutherland, say the young Blair sought adventure by replacing his Etonian uniform for that of a pukka sahib and go on ‘tiger shoots’. More recently, his misogynism and predatory attitudes toward his two wives and women in general have become an issue. These were largely forged during his time in Burma.

Burma Sahib, by Paul Theroux (Hamish Hamilton).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.