Vienna’s golden age – and its shameful secrets

Kiwi traveller explores Austrian capital’s history of fascinating contrasts.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

Kiwi traveller explores Austrian capital’s history of fascinating contrasts.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

In the middle of a Kiwi winter of discontent, it is not surprising many have taken the option of touring Europe in summer. The heatwaves and temperatures of 40 degrees or more may not be comfortable. But the pleasures and stimulation from rich cultures more than compensate.

It is difficult to choose the best or a favourite from at least a dozen cities, discounting Moscow and St Petersburg thanks to Putin’s unwelcome invasion. But the Austrian capital of Vienna, once the seat of the mighty Habsburg Empire, comes close for me.

I remember on my first OE – those days of “if it’s Tuesday, this must be Belgium” – of being tempted by Vienna after reading John Irving’s early novels before he hit the jackpot with The World According to Garp, featuring the unforgettable transgendered Roberta Muldoon.

Setting Free the Bears, published when Irving was 26, has a plot about liberating the animals in the Vienna Zoo. It also includes a motorcycle trip around Austria plus a potted history of one character’s family from pre-World War I through the post-1945 Soviet occupation to the late 1960s.

Irving spent 1963 at Vienna’s Institute of European Studies and published his first novel in 1968. Vienna also features in his next two, The Water Method Man (1972) and The 158-Pound Marriage (1974), as well as Garp.

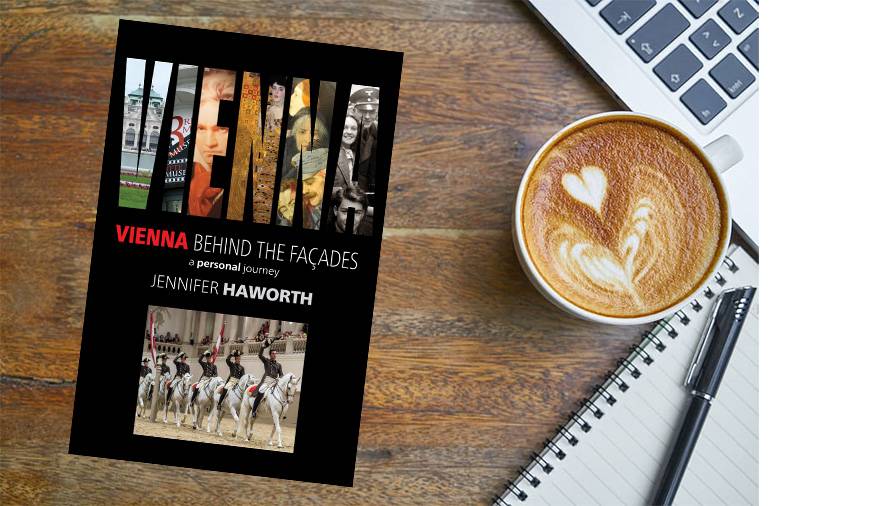

Jenny Haworth.

Christchurch writer Jenny Haworth doesn’t mention Irving in Vienna: Behind the Faςades, but her life-long fascination with the city began in 1975, a few years before my first visit. She was a teacher in the UK and, like Irving, went there to study German and learn more about its political and cultural history.

Haworth was written numerous travel books, historical fiction, non-fiction histories, and a biography, covering the fishing industry, road transport, New Zealand war artists, and the life of Robert McDougall, founder of the Christchurch art gallery.

Hidden past

Her Vienna book is billed as a ‘personal journey and promises to reveal its hidden past. In reality, it is a comprehensive guide to everything the city has to offer an inquiring tourist with the time to do more than tick a few boxes.

In 340 pages, she provides fully detailed accounts of major events in the city’s history, from the beginning of the Habsburg era in the 15th century through to the collapse of the empire during World War I, which ended Vienna’s period as the world’s most fertile cultural and intellectual centre.

Hitler addresses thousands at Heldenplatz on March 15, 1938.

That was followed by the ‘dark years’ of Der Rote Wien (Red Vienna) under socialist rule, the rise of Nazism and the Jewish purges after the Anschluss with Germany, the 10 years of Soviet occupation until 1955 and, finally, its re-emergence as the thriving capital of a Western democracy.

Haworth first tackles the historical denial that contrasts with Vienna’s past glory as a city of music, art, and intellectual thought. That period of shame started in 1938, when Adolf Hitler was welcomed home with hopes of ending poverty, social unrest, and neglect.

It ended in disaster: “By 1945, if they survived those terrible years of oppression, war, rape and looting, those people would never admit they lifted an arm to celebrate the arrival of their one-time hero,” Haworth says.

Intrepid journey

Her intrepid journey through dozens of museums, art galleries, concert halls, palaces, monuments, and historical buildings uncovers much more than the touristic icons of the Spanish Riding School, Vienna Boys’ Choir, and the Prater’s giant wheel.

Vienna viewed from the Upper Belvedere place. Photo: Jenny Haworth.

Vienna’s rise to rival the other great European imperial capitals was already apparent in 1700 when it boasted some 400 baroque palaces, including the Belvedere, the Prunksaal (library), which had 9000 items in 1575, Karleskirche, and Stephansdom. Empress Maria Theresa, ruler from 1740-70, added the rococo Schönbrunn palace and established her husband Franz Stephen as Holy Roman Emperor.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 made Europe safe for aristocracies, spawning economic growth with industrialisation, railways, and another building boom. Emperor Franz Josef (1848-1916) removed Vienna’s walls, replacing them with the 5.3km Ringstrasse, along which were built magnificent civic facilities, theatres, museums, galleries, hotels, and coffee houses – all modelled on the imperial grandeur of ancient Greece and Rome.

Outside the Hundertwasser Museum in Vienna. Photo: Jenny Haworth.

Artists, architects, writers, philosophers, scientists, and musicians transformed the city’s cultural life. It was an era where socialites danced to the waltzes of Johann Strauss (senior and junior), Schubert, Haydn, and Mozart, while concertgoers heard performances of Beethoven and the contemporary works of Richard Strauss, Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler, Schönberg, Lehár, Berg, and Webern.

In literature, Arthur Schnitzler and Stefan Zweig wrote of a society that had lost its inhibitions, while artists such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele defined a new era of modernism.

Shared ideas

Carl Schoske, in his definitive Fin-De-Siecle (1961) provides this summary: “The salon and the café retained their vitality as institutions where intellectuals of different kinds shared ideas and values with each other and still mingled with a business and professional elite proud of its general education and artistic culture.”

The Jewish population alone was 145,000 and highly influential, dominating finance (71%), law (65%), medicine (59%), and journalism (50%). But this flowering also bred ideologies that Haworth says, “in the end destroyed the ordered world of the emperors”. At this time, Vienna had a population of two million at the centre of a multinational cornucopia of 60 million people of different ethnicities, languages, and religions.

“Concepts of nationalism, liberalism, radical socialism, communism, and even anti-Semitism were all part of the Viennese story which flood on into the 20th century,” Haworth writes.

World War I, in which the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary fought with Germany against Russia and Italy, brought the edifice down as the various ethnicities refused to fight for Germany. Out of eight million mobilised troops, Austria lost one million with another two million wounded.

Food shortages and hunger from 1916 fuelled strikes, along with demands for democracy. After 1918, Vienna was reduced to the capital of a rump country of just six to seven million, many of them Jewish refugees from more-eastern parts of the former empire.

Socialism reigned briefly, bringing much-needed housing and other social reforms, but that stopped with the collapse of Creditanstalt in 1929 and Wall Street’s Great Depression. Haworth has no room to mention that other great intellectual movement of that time, the Vienna Circle, which pitted free market economics against socialism, transformed modern philosophy, and added vastly to the knowledge of physics, logic, and mathematics.

These advances spread to the US and Britain after the Nazi takeover, ensuring a lasting reminder of Vienna’s greatness.

Museums and galleries

Haworth is knowledgeable about the Nazi looting of treasured paintings and provides a valuable run-down of Vienna’s most interesting museums and galleries, of which only a taste can be given here.

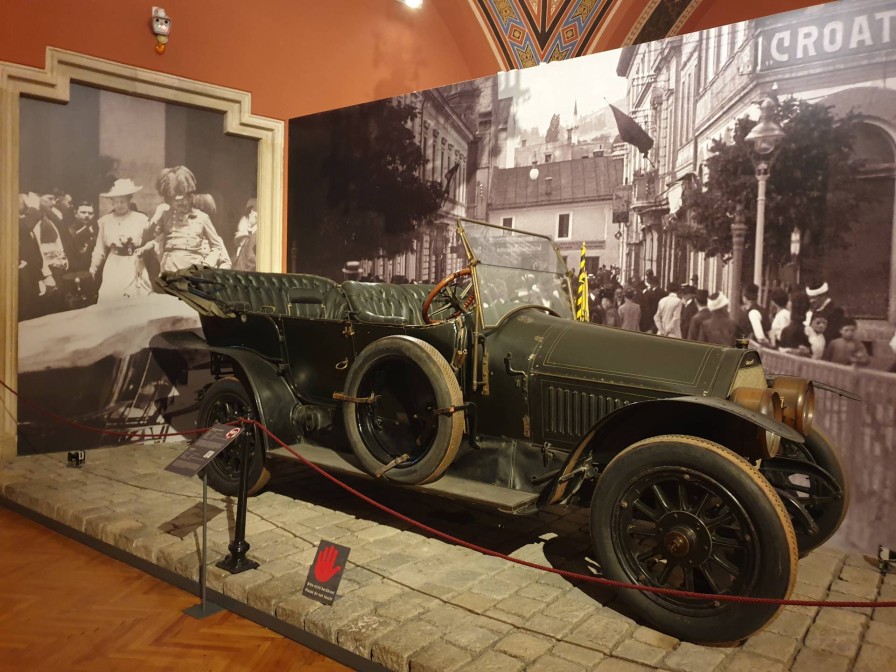

Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s car in the HGM. Photo: Josie Welch.

Model of the sewers at The Third Man Musuem.

Vienna: Behind the Facades: A personal journey, by Jennifer Haworth (Wily Publications).

Related reading (not mentioned above):

The Age of Insight, Eric Kandel (2012). A psychological study from 1900 to present day.

The Hare with Amber Eyes, Edmund de Waal. A history of a prominent Jewish family, the Ephrussis.

Marginal Revolutionaries, Janek Wasserman (2019). The Vienna Circle and its legacy.

Night Falls on the City (1967) and A Place in the Country (1969), Sarah Gainham (aka Rachel Stainer Ames). Novels set in Vienna during and after World War II.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.