Unfinished business: Tax fraud trial revisited

Digi-Tech case revived in 'creative non-fiction' thriller alleging corruption and coverup.

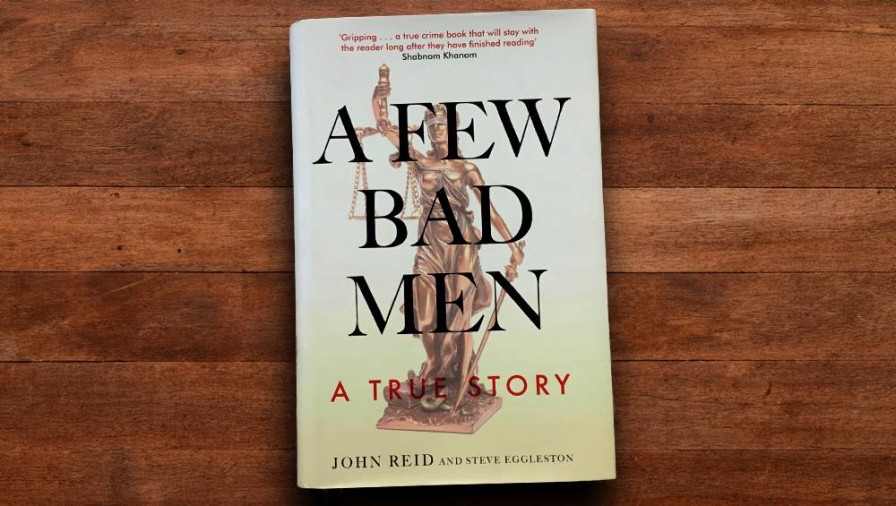

A Few Bad Men: A true story, by John Reid and Steve Eggleston (Halo Books)

Digi-Tech case revived in 'creative non-fiction' thriller alleging corruption and coverup.

A Few Bad Men: A true story, by John Reid and Steve Eggleston (Halo Books)

Financier John Reid, who was exonerated along with three co-defendants in the 2004 trial involving a Digi-Tech tax scheme, has published his version of events in a 400-page book. In it he alleges a conspiracy and coverup by at least 10 officials from Inland Revenue and the Serious Fraud Office – hence the title, A Few Bad Men: A true story.

Reid, his wife Robbie and their son Sam, now 27, left New Zealand in 2014 and are now based in the Isle of Man, a low-tax territory in the Irish Sea. He said he could never overcome the “stigma and shame” by staying here, even though he was acquitted. He delivered a copy of the book to me when I was recently in London.

After the case’s dismissal in the High Court by Justice John Fogarty, and a later hearing for costs in the Supreme Court in 2007, Digi-Tech was again back in courts in 2011 in a claim against the investors that was abandoned. A case of malfeasance against the IRD did not go ahead after the Court of Appeal ruled the plaintiffs, including Reid, had to post security for costs of $200,000.

Reid co-founded merchant bank Milloy Reid in 1989 when only 26 after "making his first million dollars". He has vividly brought back to life the heady days of the 1990s and early 2000s after financial deregulation during the fourth Labour government. This is a gripping read that reveals much more than the public record has previously revealed.

Reid describes the book as “creative non-fiction” and has written it in the third person with the assistance of Steve Eggleston, a professional ghost writer with several titles to his name.

John Reid with his ring-binder files.

Their collaboration took four years and was partly based on extensive files – 250 ring binders containing 80,000 pages – that Reid created from SFO documents. This was not exhaustive, as Reid claims many more were withheld that did not support or even contradicted a criminal case of fraud against some 130 investors.

Milloy Reid was a provider of venture capital and Digi-Tech was first brought to its attention in 1994 by elite accountancy firm Gosling Chapman. Tax avoidance schemes abounded, and Gosling Chapman’s one for Digi-Tech had plenty to offer wealthy clients who wanted to reduce their tax burden.

The question was whether these schemes, ranging from forestry and goat farming activities to high-tech ventures and mining, were legitimate businesses or investment scams.

To cut a long story short, the IRD was convinced Digi-Tech fell into the latter category. After a four-year investigation, Reid was interrogated by an IRD team who alleged fraud and later refused to give investors their expected writeoffs.

Gosling Chapman turned “queen’s evidence” and tried to put the blame for its clients’ losses on Reid. From then on events went from bad to worse, as Reid’s business dried up, his private life was affected by excessive drinking, and he faced a criminal trial with a potential jail sentence.

The charges were laid on March 12, 2002, against Reid and three others. After an unnamed QC demanded a million dollars up front to handle the case, Reid decided to run his own defence with Murray Gilbert, later a High Court judge, as counsel.

Justice Murray Gilbert on his appointment to the High Court.

Gilbert is one of the few “goodies” and among many “baddies” who, except for the QC, are all named in what might be a field day for defamation lawyers if it wasn’t for some of them having subsequently died.

The depositions hearing in 2003 was a warmup for Reid, whom Eggleston compares with a quote from Hemingway’s character Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea: “A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”

Missing documentation of meetings Reid had with the IRD prompted him to summons 135 individuals from the IRD, SFO and Gosling Chapman, as well as 123 investors. The tactic paid off and two years of preparation gave Reid and Gilbert some hope they could win the case despite the odds.

A portent was that top barrister Jim Farmer QC (and now KC), who was acting for the Crown, did not give the opening address because of his America’s Cup commitments. Farmer’s role in the trial, which ran for five weeks from September 12, 2004, is a matter of conjecture, with Reid relating a roadside conversation with Farmer, telling him the scheme was not a scam, and that the SFO was withholding documents.

In his version, as told in the book, Farmer doesn’t recall the roadside incident or that he had received evidence from Reid that Farmer had misled the court, something Farmer denied he would ever do.

Robbie Reid and Steve Eggleston during the book's preparation.

Much of the trial is told through the eyes of Robbie Reid, who describes the contempt shown to her by the aggrieved investors and even some of the co-defendants. This may explain the “creative” part of a non-fiction story, but it certainly adds drama to the characters and events.

For example, an SFO investigator’s reaction to shoulder-shoving Robbie on his way to the toilet must be imagined. More drama follows when Reid and Gilbert decide not to offer a case for the defence, confident their cross-examination of prosecution witnesses had done their job.

Justice Fogarty agreed, verbally dismissing all the charges and in a later written decision backing up many of Reid’s allegations of shortcomings in the IRD and SFO’s handling of the case. The next day, October 15, 2004, NBR’s lead headline was: “Shock verdict clears tax fraud accused.”

Media coverage of the Digi-Tech case.

But the story doesn’t end there. In the washup, Gosling Chapman settled with a $10 million claim from its clients and ceased trading in 2002. It became part of the WHK Group. The defendants received $1.1m in compensation from the Crown in 2005. Both the SFO and its prosecutors were criticised for misleading Justice Fogerty at the costs hearing.

Reid’s call for an inquiry into both entities was rejected and confirmed by Attorney General Michael Cullen, who was responsible for them.

In 2007, SFO director David Bradshaw and assistant director Gus Wiltens both left and Attorney General Cullen took steps toward the agency coming under control of New Zealand Police, which has also rejected attempts by Reid to investigate his claims of false, suppressed and destroyed documents.

The other assistant director of the SFO, Gib Beattie, stayed on for a while but would soon leave to form his own firm. He later acted for the five directors of collapsed South Canterbury Finance in 2014 in an SFO case where only one was found guilty of five out of nine charges he faced.

Others prominent in the Digi-Tech trial on the prosecution side were appointed to government posts, including the District Court bench. Defence counsel Gilbert retired after being appointed to the High Court in 2012 and the Court of Appeal in 2017.

Whether Reid succeeds in getting any traction to gain redress against the “bad men” remains to be seen. The book contains serious allegations of abuse of power, but these are rarely pursued against the people responsible, even after being established by commissions of inquiry.

Reid may have to settle for the book being widely read and the completion of a movie adaptation promised on his website, which has an outline of all his claims.

A Few Bad Men: A true story, by John Reid and Steve Eggleston (Halo Books). Also available as an ebook (https://afewbadmen.online/).

A Few Bad Men: A true story, by John Reid and Steve Eggleston (Halo Books). Also available as an ebook (https://afewbadmen.online/).

Disclosure: The NBR provided the main media coverage of the Digi-Tech case over 10 years. Deborah Hill’s lively trial reports are still worth reading today. As editor at the time, I think Reid treats us fairly despite his view that we were part of the forces aligned against him. We both had premises at the then BNZ Tower, 125 Queen St, Auckland.