Two colonials who helped create the nuclear world

ANALYSIS: Joint biography depicts the Antipodean friendship of Ernest Rutherford and Marcus Oliphant.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Joint biography depicts the Antipodean friendship of Ernest Rutherford and Marcus Oliphant.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Auckland’s CBD has only one shop selling serious books compared, say, with Masterton’s three. Unity Books in High Street, an offshoot of its bigger sibling in Wellington, is smaller than the average Whitcoulls or Paper Plus in suburban malls.

Unity is so cramped for space that books are piled up in the window. Not in recent weeks, though. In a rare stroke of imaginative marketing, Unity has embraced ‘Barbenheimer’, the Hollywood bonanza of opening two blockbusters simultaneously around the world.

By the second weekend, Barbenheimer had grossed US$1.17 billion worldwide, with Barbie outselling Oppenheimer by two to one. That is not surprising, as the two movies are like chalk and cheese.

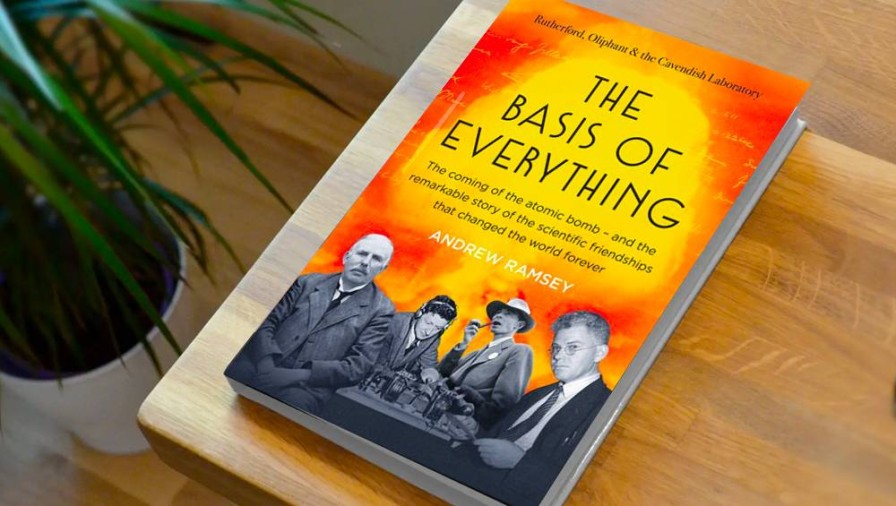

The Unity window is dominated by Barbie’s pink paraphernalia and not too many books. Oppenheimer has fewer linked items of merchandise, noticeably Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin’s mammoth biography, American Prometheus (2005); Energy by Richard Rhodes; and Andrew Ramsey’s The Basis of Everything (2019), just scraping in at the bottom left in the picture.

I opted for the latter in its new paperback edition because it was not about J Robert Oppenheimer but the science of what made nuclear bombs possible. In fact, it’s an Anzac story of two men, a New Zealander and an Australian, aged 30 years apart.

Both grew up as colonial boys, with an appreciation of the outdoors, raised by hard-working pioneer parents, with a strong commitment to education despite being half a world away from the centre of European civilisation.

Ernest Rutherford, later Baron Rutherford of Nelson, was born in 1871 to the family of a flax farmer on the Waimea Plain. Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, later Sir Mark, was born in 1901 and raised in Adelaide. He was to become Australia’s foremost scientist and founder of the Australian National University.

Both collaborated as experimental physicists in the 1930s at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory on the development of nuclear energy, which led to the weapons depicted in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. Neither, by the way, get a mention in the film.

Andrew Ramsey.

While Ramsey, best known as a cricket historian based in South Australia, grew up knowing of Oliphant’s life and achievements, he is equally effusive about Rutherford. The book is illustrated with many of Oliphant’s photos, has extensive source notes and a bibliography, but no index.

In telling two parallel lives, which crossed for only one decade, Ramsey emphasises their shared colonial mindsets and values. He also insists that Rutherford was Oliphant’s mentor up until the former’s death from failed treatment of a strangulated hernia on October 19, 1937, aged 66 and four years from his planned retirement.

They first connected when Oliphant, as a student, attended a lecture Rutherford gave in Adelaide on one of his frequent trips to Australia and New Zealand. Rutherford later recognised and recruited Oliphant for the Cavendish as someone “who matched their intellectual prowess with an ability to get things done”.

Rutherford’s humble beginnings and education, at primary school in Havelock and as a boarder at Nelson College, were noted for his avid reading as well as his practical knowledge. He learned Latin and French as well as mathematics and the core sciences.

He was head boy and won a scholarship to Canterbury College, before it became an independent university. In 1890, it had 150 students. Rutherford was one of two finalists for an imperial scholarship to Cambridge in 1895. He gained it after the first choice had to pull out because he had married and could not afford to go.

Nelson College sports day in 1920. The original wooden building, which Rutherford attended from 1887-89, was destroyed by fire in 1904.

In Christchurch, Rutherford’s girlfriend was his landlady’s daughter, Mary Newton, but they did not marry until 1900 after a four-year engagement. To support them both, he had accepted a position at McGill University in Montréal, Canada.

They went to England nine years later when Rutherford became head of physics at Victoria University of Manchester which, like many other institutions, was competing with Cavendish in researching atomic structures. Ernest Marsden, another Kiwi, was among those ‘splitting’ atoms, such as nitrogen into hydrogen and oxygen, thus releasing the energy in Einstein’s famous E=mc2 formula.

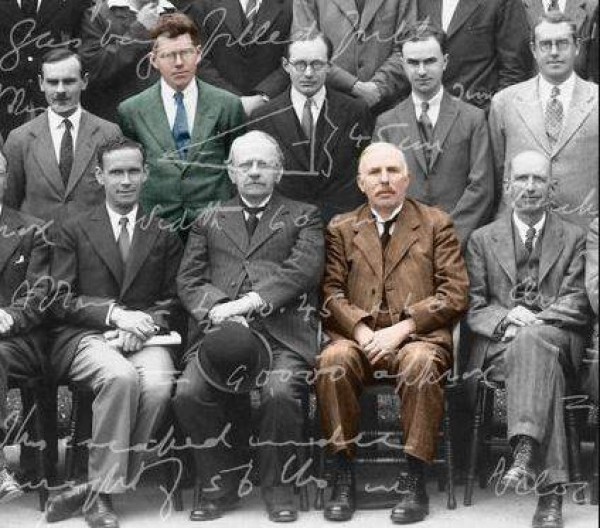

JJ Thomson, right, preceded Rutherford as director of the Cavendish Laboratory. This picture was taken in the 1930s.

Rutherford received the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1908 for his work in radiation and was knighted in 1914 for his model of the atom, developed by firing particles through gold foil. He had jibbed at Cavendish’s class-ridden and gender-discriminatory practices. But when its long-standing director JJ Thomson retired, Rutherford was offered and accepted the job in 1919.

Thus began the golden era at Cavendish. Among the many discoveries was the existence of a neutron in addition to the proton and the electron (which Rutherford had foreshadowed in 1920). Oppenheimer briefly visited Cavendish but as a theorist he was not impressed by Rutherford’s experimental methodology. The feeling was mutual after Oppenheimer tried to poison his tutor, an incident shown in Oppenheimer.

When Oliphant, aged 23, arrived at Cavendish with his 21-year-old bride Rosa, the Rutherfords immediately welcomed them into their private lives by sharing their colonial love of the outdoors at a country home in Wales.

On his trips abroad, Rutherford left Oliphant in charge of Cavendish and encouraged him to accept a professorship at the University of Birmingham, which had attracted large donations from private industry for what had become ‘big science’.

By contrast, Rutherford’s loathing of private funding, and his focus on science as a public good, had resulted in Cavendish falling off the pace due to lack of the equipment needed for further advances.

Cavendish Laboratory staff picture in 1932. Oliphant and Rutherford are highlighted in colour. Detail from alternative cover for Andrew Ramsey’s ‘The Basis of Everything’.

Rutherford was made a member of the House of Lords in 1931, and three years later joined Einstein, the world’s other most famous scientist, in an initiative to give refuge for many German Jewish intellectuals. Both recognised the threat of Nazism, but expressed fears that nuclear energy could be turned into weapons.

Just as he agreed to build the particle accelerator that Oliphant had wanted, Rutherford’s hernia fatally intervened. Oliphant left for Birmingham in the same year, 1937, as Rutherford was buried at Westminster Abbey. Lady Rutherford returned to Christchurch at the end of the war, dying there in 1954 aged 77.

The final third of the book follows Oliphant as his career took him to the US, back to England, and finally his homeland. As World War II loomed, Oliphant was convinced nuclear energy should be harnessed in the fight against tyranny.

He also defended Rutherford’s reputation from claims that his mentor was responsible for the atomic bomb. “[He] discovered the nucleus, invented the methods for investigating its properties, and showed that nuclear transformations were accompanied by emission or absorption of energy enormously greater than the energies associated with chemical reactions.”

Apart from the bomb, these discoveries created radiotherapy, cathode ray and digital screens, the worldwide web, and mass spectrometry.

From left: Mark Oliphant, British scientist John Cockcroft, J Robert Oppenheimer. 1948. Photo: University of Adelaide.

Though Oliphant participated in the conception and delivery of the Manhattan Project, most of his work did not occur with Oppenheimer at Los Alamos. Instead, Oliphant was at Berkeley in San Francisco where a huge cyclotron, known as the calutron, could generate sufficient electricity to produce the fissionable isotype for the uranium-based detonation in the bomb used at Hiroshima.

Oliphant left the Manhattan Project before its conclusion because he no longer felt at the centre of the action, according to Ramsey. Like many others involved in the bomb’s creation, Oliphant later regretted its use against civilians. But by then, as Rutherford had warned, the scientists were at the mercy of politicians and the military.

On his return to Australia, Oliphant led the establishment of the ANU, eventually accepted a knighthood in 1959, and was governor of South Australia from 1971 to 1976. He died in 2000, aged 99, having lived through an entire century.

In his epilogue, Ramsey again draws on the two men’s similarities despite being from different generations: “rare gems hewn from unique environments”. It’s fitting a description as the world still grapples with the fallout from their legacy.

The Basis of Everything, by Andrew Ramsey (HarperCollins).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.