True crime and the dime novel solution

ANALYSIS: Movie writer John Evan Harris wants to turn boys on to the adventure of reading.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Movie writer John Evan Harris wants to turn boys on to the adventure of reading.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

The literary editor of The Australian, Caroline Overington, caused a minor sensation earlier this year when she reported the comments of Susanne Horman, owner of the Robinsons chain of bookshops in Victoria. Horman had accused the publishing industry of gender and racial bias – against white men and boys.

“What’s missing from our bookshelves in store? Positive male lead characters of any age, any traditional white family stories, kids’ picture books with just white kids on the cover, and no wheelchair, rainbow, or indigenous art, non-indigenous history,” Horman was quoted as saying.

Naturally, there was pushback from the industry, authors, and other booksellers. However, Overington backed Horman, admitting she had “expressed herself clumsily, suggesting that she was a bit over all the ‘rainbow’ books and children’s books with kids in wheelchairs on the cover, but she’s not wrong about Australian publishers”.

Overington continued: “They absolutely have been pushing books by female writers, who now take up practically all of the spots on the bestseller lists, as well as books by Indigenous writers, and writers from other minority groups…

“Maybe it’s time for the publishing industry to do a little more to help men get published. It’s an idea that would have seemed ridiculous, even 20 years ago. Male writers have dominated literature for centuries.”

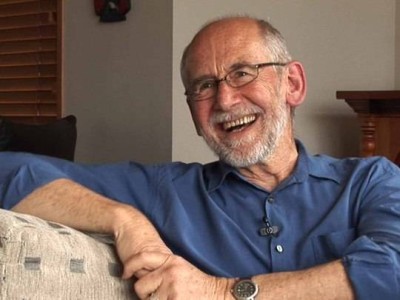

John Evan Harris.

Is it any different on this side of the Tasman? Some would agree the dominance of women writers is an indictment on the industry, and poses the question of why males have become invisible or face extinction. Readers may recall actions by major global publishers’ female staff to prevent publications by Jordan Peterson or JK Rowling because of the authors’ views.

The longlist for this country’s top fiction prize in the Ockham book awards has a sole male among the 10 selected. Last year’s seven longlisted male authors were an exception rather than the rule in recent years.

The eight NZ Booklovers fiction award finalists offer another perspective, with a 50-50 breakdown of men to women, with a strong bias to toward crime and popular fare rather than serious literature. Smaller publishers are also strongly represented. This reflects the self-publishing industry, which has proved relatively lucrative for some male writers.

Among Horman’s concerns were a lack of titles to encourage reading among boys. That gap brings us to the work of John Evan Harris, best known as a screenwriter and founder of Greenstone TV, which has just celebrated 30 years in business. It specialises in documentaries and reality shows, though more recently it has moved into scripted dramas. Harris sold his interests in 2014.

One of Greenstone’s early successes was Epitaph, a true crime series presented by Paul Gittins. It had four series between 1996 and 2001, with 39 half-hour episodes. Among them was an exploration of the Maungatapu murders of 1866, described in the 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand as the Maungatapu Mountain Killings and “one of the most grisly crimes perpetrated in this country”.

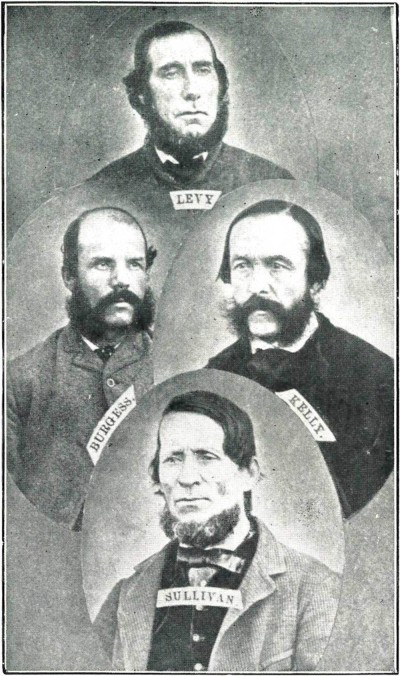

The Burgess gang pictured shortly after arrest in June 1866.

That was before the days of mass murders, but they remain a key event in Nelson’s colonial history. Historian Jim McAloon describes them as sending the town into “a spasm of terror and excitement”.

While the Maungatapu bridle track between Nelson and the short-lived Wakamarina goldfields near Havelock in the Marlborough Sounds was never developed into a road, the location where four men were ambushed for their gold and cash is still known as Murderers Rock.

The quartet of two storekeepers, a hotelier, and a miner had valuables worth £300 ($35,000 in today’s money) and their disappearance prompted a widespread search. Four suspects, Philip Levy, Richard Burgess, Thomas Kelly, and Joseph Thomas Sullivan, were soon arrested but it was not until one of them, Sullivan, turned Queen’s evidence for a £200 reward that the bodies were found.

The search also uncovered a fifth victim, who had been ambushed earlier that day by mistake. Three of so-called Burgess gang were put on trial and subsequently executed. Sullivan did not collect his reward because he was charged and found guilty for his role in the fifth murder.

He escaped the hangman’s noose for a life sentence but was deported back to Britain due to the hostility of other prisoners. All four had come to New Zealand from the goldfields in Victoria to check out what Otago and West Coast had to offer. They were already responsible for a series of crimes. Three had been transported as convicts from Britain for what would today be considered minor crimes.

The exception, the ‘businessman’ Levy, was a dealer in gold and known as a ‘fence’ – a receiver of stolen goods. The Supreme Court trial in Nelson was noted for a lengthy confession written by Burgess, who acted in his own defence. That included his 15-hour cross-examination of Sullivan as a witness. The judge’s summing up took six hours, but the jury delivered its verdict within an hour.

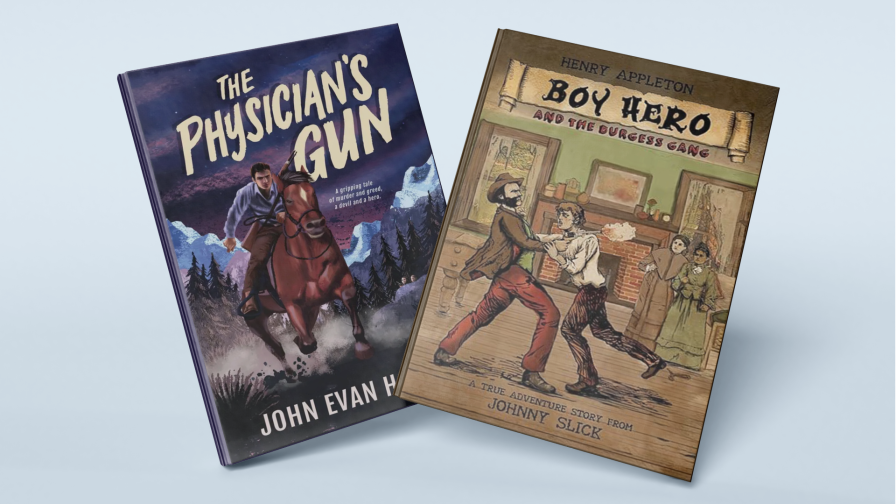

A couple of years ago, after unsuccessfully attempting to get a feature film based on the Epitaph episode off the ground, Evans used his extensive research for a self-published 300-page book, The Physician’s Gun. This was aimed at what publishers call the ‘young adult’ market as it recounts the Burgess gang’s exploits through the eyes of a 15-year-old character, Henry Appleton.

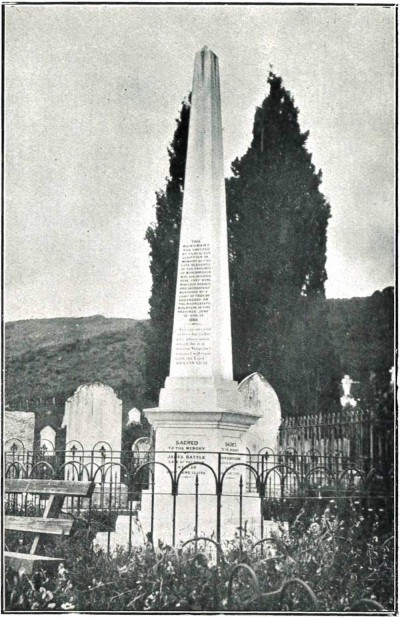

Monument at Wakapuaka cemetery to the five murder victims.

It reads like a movie script and, as well as the protagonist being in every scene, it pays homage to the American tradition of dime novels – cheap paperback fiction that was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The content was mainly about masculine adventures at sea, the Wild West, goldminers, circuses, and railways. They filled the leisure needs of newly-literate working class men and boys.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, dime novels, also known as pulp fiction, became collectors’ items; the University of Minnesota has 65,000 in its Hess collection. Young Henry Appleton was addicted to dime novels, even while being part of one himself in Harris’s telling.

Part of his invention is a visiting dime author, Johnny Slick, who attended the Burgess gang trial in September 1866 and learned of Appleton’s involvement. Nine years later, when Appleton has become a medical doctor, he receives a copy of Johnny Slick’s dime-story, Henry Appleton: Boy Hero and the Burgess Gang. This enables Harris to rework his earlier novel into a racier version that, at just under 200 pages, is excellent night-time reading for those who might find The Physician’s Gun heavier going.

Both books have additional material citing written and pictorial sources, displays at the Nelson Provincial Museum, and places of interest. These include a memorial to the Maungatapu victims at the Wakapuaka Cemetery north of the city.

One source not quoted by Harris is Death Round the Bend, by historian J Halket Millar, published by Nelson bookseller RW Stiles in 1954. I was eight at the time and the book remains one of my prized possessions from growing up in Nelson.

Strangely, McAloon does not reference Millar’s book, though two of his others are mentioned. Like Harris, I have always envisaged the Maungatapu murders would make a great movie, using Millar’s title.

The Physician's Gun, by John Evan Harris (Roiall Emerald).

Henry Appleton: Boy Hero and the Burgess Gang, by John Evan Harris (Roiall Emerald).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.