True believer explodes myth of neoliberal capitalism

ANALYSIS: Easy money and high-spending governments are not a recipe for growth.

ANALYSIS: Easy money and high-spending governments are not a recipe for growth.

Saturday mornings are considered a dead spot in the weekly news cycle. Last weekend was an exception with the Oval Office’s boilover on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Another, from my childhood, was the assassination of President John F Kennedy.

But the most memorable one occurred exactly 40 years ago when I was the duty editor at the public radio broadcaster. March 2, 1985, was a normally quiet Saturday until the newsroom at Broadcasting House next to Parliament heard about the flurry of activity at the Beehive, the Treasury and the Reserve Bank.

Political editors had been tipped off and the floating of the New Zealand dollar was officially announced at 10.30am, coinciding with the close of currency trading on Wall Street.

A news special at midday brought out all the usual suspects – explanations from ministers and advisers, the opinions of business and rural lobbyists, and a handful of opponents. In those days, public radio reporting was supportive of the Labour Government’s sweeping economic reforms to remove the last vestiges of Muldoonism.

The aim was to inform the public about the reasons for change, rather than RNZ’s preference today of providing a platform for those opposed to austerity in public spending or, more likely, calls for more.

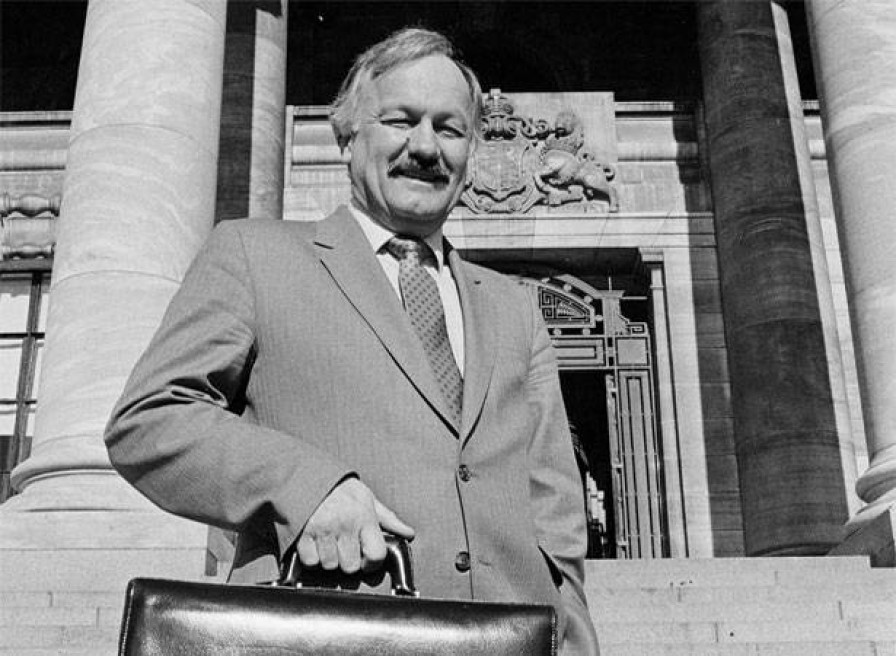

Finance Minister Roger Douglas planned to float the NZ dollar after the 1984 devaluation.

Dissident voices to the float included economist Brian Easton and then trade unionist Rob Campbell. A float had long been the goal of the reformers since the devaluation of July 1984.

Former Reserve Bank economist Michael Reddell recalled the event in his Croaking Cassandra blog much more vividly than I can. A floating dollar was seen as New Zealand joining the world of sophisticated economies.

It has since been widely accepted as a normal part of life, despite fears a float would wildly over value the so-called “kiwi” and nullify the effects of the 20% devaluation eight months earlier.

Easton repeated his criticism in his economic history, Not in Narrow Seas, but devotes less than a page to what he describes as the “most important price in the economy”.

Reddell went into the technicalities and the dangers of capital flight at a time when the economy was in a parlous state. (The overnight cash rate was 38% and 90-day bills 25%). He described the first few weeks as a “wild ride”, with the overnight rate rising to 265% (peaks were more than 500%) and 90-day rates at more than 35% until settling at 24% by March 20.

Reddell said other options to a clean float were considered but he concluded with hindsight that New Zealand escaped a bullet by having a financial boom that “might well have been even larger, and ultimately messier to resolve, than what we were actually to experience a few years later”.

Other countries, such as the Nordics and later Spain and Ireland, used other methods to manage their currencies and paid a higher price. Despite much volatility in the early years, and a few scandals involving speculation, the kiwi has remained uncontroversial for the past 15 years.

A more seminal event for many economists around the world was the introduction of inflation-targeting by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1990. Until then, central banks were the main cause of inflation through pumping up growth by printing money.

Ruchir Sharma.

Morgan Stanley economist Ruchir Sharma first noted New Zealand’s pioneering role in Breakout Nations (2012), a study of the “next economic miracles”. India-born Sharma, a self-described true believer in capitalism, was recruited by Morgan Stanley because of his investment analysis on emerging economies.

Breakout Nations became a global sensation among economic books for its real-world evidence and policies that made some countries better off than others. He elaborated on this theme in The Rise and Fall of Nations (2016), which again mentioned New Zealand’s “success story” with inflation and how it had been followed by a dozen or more other countries.

Readers looking for positive news about New Zealand’s prospects will be disappointed by Sharma’s latest book, What Went Wrong with Capitalism. It has only two brief references, one about the world’s lowest level of lending by non-bank institutions, and other about women’s suffrage.

Sharma, who left Morgan Stanley in 2022 for his own financial businesses, Rockefeller Capital Management and Breakout Capital, now researches why capitalism has performed so badly in this century.

This is not the capitalism viewed from the left, exemplified in recent titles such as Joseph Stiglitz’s The Road to Freedom, Martin Wolf’s The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, and Ulrike Herrmann's The End of Capitalism.

Rather, Sharma provides a litany of how democratic politics and the welfare state have destroyed capitalism’s strengths. He blames large government financial deficits and rising debt.

While New Zealand is not referenced, and Sharma concentrates on the largest and most developed capitalist societies, his analysis is relevant through its replication in the local scene on a smaller scale.

He describes the neoliberal era, from the deregulation days of Margaret Thatcher and her acolytes in Ronald Reagan’s United States and elsewhere, as a myth. Governments did not get smaller, and capitalism’s productive role paid the price.

Margaret Thatcher in 1984 at the start of the neoliberal era.

The state is more dominant than ever in most advanced economies. Taxes are also close to peace-time highs as a percentage of income. Excessive government spending and greater regulation have cramped productivity and growth, shrinking the pie for everyone and stoking public anger.

Inequality worsened as the burden of public debt increased in the belief this would allay demands for relief from hardship and setbacks. That includes a strong dose of corporate welfare.

While the abovementioned books blame capitalism for the common social ills, Sharma reverses the cause by pointing to the state’s greater interventions and distortions resulting from an addiction to debt.

His reasons are documented with an historical sweep through recent centuries and modern examples such as Japan’s experience with deflation. Sharma contends earlier periods of deflation in the United States – mainly caused by technological advances – had occurred from 1870-1914 and the 1920s. Growth was steady at 3% while consumer prices fell.

However, Japan’s deflation in the 1990s was the hangover from a debt-fuelled bust, undermining consumer confidence and demand. The fear of Japanese-style deflation in the dotcom bust in 2000, the housing bust of 2008, and the pandemic of 2020 was unwarranted.

The Bank for International Settlements in Basle, Switzerland.

“Economic leaders were fighting the wrong war with good intentions,” Sharma argues. “This is the tragedy: for more than two decades now, central banks have been flooding the world with easy money to stave off any hint of deflation even in good times, fuelling asset bubbles that, when they pop, are the most likely source of bad deflation.”

The response included dropping interest rate to near-zero and central banks buying bonds – including privately issued ones – to counter the business cycle. Billions of dollars were created, setting off another round of inflation. This “rescue culture” of bailouts involved governments underwriting public projects, pension funds, healthcare costs, bank deposits and mortgages.

Central banks had moved from fighting inflation to ensuring full employment and stabilising financial markets at home and abroad under a “mission creep” awarded them by politicians of the left. Sharma notes how this expanded to include climate change and combating racial discrimination, a formula that also had a deleterious effect on New Zealand’s chances of recovery.

Sharma’s list has many more examples that also apply to New Zealand: ‘zombie’ companies that cannot cover their cost of capital (applicable to enterprises in the public sector); thicker and more complex rules encasing the markets (the Financial Markets Authority); a lack of productivity improvements (16% of a worker’s time may be spent in reviews, compliances and forms of red tape).

This grim analysis is backed up by evidence that economic growth in developed economies is not likely to exceed 2% in future, with half of that coming from population increases, including immigration.

The one glimmer of hope is that not all economies have embraced the debt addiction. Sharma finds three positive case studies: high-income Switzerland, middle-income Taiwan, and low-income Vietnam.

The latter two provide hope for New Zealand, given their proximity and size. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon’s recent choice of Vietnam for a trade mission is a sign of a message getting through. Sharma describes Vietnam as a “functional communist state” that resembles China 20 years ago as it began to embrace capitalism.

China has since turned down the authoritarian path and demonstrates many of the weaknesses Sharma exposes. “Capitalism is still humanity’s best hope for economic and social progress, but only if it is free to work.”

What Went Wrong with Capitalism, by Ruchir Sharma (Simon & Schuster).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.