The work of the poor is never done

Irish-turned-Kiwi broadcaster’s memoir recalls a mother of tears and beers.

Irish-turned-Kiwi broadcaster’s memoir recalls a mother of tears and beers.

The conventional wisdom is that the poverty and inequality gaps widened during the Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is fodder for the popular media, and rising petrol prices usually herald an economic pullback as monetary policy is tightened to combat inflation.

Those with memories of the 1970s and 1980s will recognise the symptoms and solutions, possibly also drawing conclusions about whether this generation of politicians and central bankers has learned anything.

Recent statistics muddy this picture of worsening circumstances. For example, child poverty declined on two out of the three key measures before and during the pandemic. The number of children in families unable to afford necessities, such as clothes and heating, fell by 6000.

Clearly a win for a touchstone government policy. Furthermore, income inequality reduced in the four years to June 2021, while wealth inequality data showed no overall change between 2018 and 2021.

The share of assets held by the wealthiest 1% declined fractionally, from 20.1% to 20.0%.

In quantitative terms, 20,000 children have been lifted above the poverty line since 2018, though another 150,000 are still below it, on one measure. I took these figures, based on official data, from a recent article by Max Rashbrooke, whose Too Much Money is the campaigner’s handbook for higher taxes on all who work, and larger benefits for those who don’t.

Assumptions challenged

A 2016 New Zealand Initiative publication, by Bryce Wilkinson and Jenesa Jeram, challenged many of the assumptions in the poverty estimates and how they are measured.

Outside of the statistics, literature views poverty as a springboard to life’s better experiences. Few writers admit they grew up in a comfortable bourgeois homes.

PJ O’Rourke, a conservative satirist and foreign correspondent who became rich and famous by making fun of socialists, came from a “working poor” background in the American rust belt. JD Vance, author of the autobiographical Hillbilly Elegy, is seeking election to the US Senate as a Republican.

‘Misery memoirs’ are such a lucrative genre that many have been exposed as false. No-one wants to read about a boring life that didn’t have poverty, slums, physical abuse, divorce, racial discrimination, drug addiction, or alcoholism at its core.

UK industry publication The Bookseller estimated sales of such memoirs peaked at about 2008, with one title selling more than 300,000 and total sales of £10 million. Another resulted in a mother suing her daughter over claims her story of a “loveless childhood” was a “piece of fiction”.

The greater the exaggeration of misfortune and mistreatment, the better the sales. The all-time champion is Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes (1996), about an immigrant Irish family in Brooklyn, New York. Another American, Dave Pelzer, spun his life with an alcoholic mother into three books, courting controversy when much of it was said to be invented.

‘Recovered memories’ were also in vogue, and many will recall the fate of Peter Ellis in Lynley Hood’s exposé, A City Possessed. Celebrated hoaxes included James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces (2003), Kathy O’Beirne’s Kathy’s Story’s (2005), and Margaret Seltzer’s Love and Consequences (2008).

Poverty industry

None of this suggests any New Zealand writer is guilty of such deceptions. The poverty industry is largely confined to academics and activists with political agendas. These groups quote extreme examples of children from households of 16 in south Auckland going to school hungry, though such circumstances would qualify for substantial benefit income.

Hardship is a common theme in Kiwi writers’ memoirs and fiction, notably John A Lee’s Children of the Poor (1934), though his mother Mary’s autobiography was called The Not So Poor (written during her lifetime, 1871-1923, but not published until 1992). Lee, as a politician in the first Labour government, can claim some credit for the welfare state, though his radicalism led to his expulsion from the party in 1940. He was MP for Auckland East, 1922-28, and Grey Lynn 1931-43.

Lee enjoyed a resurgence in the revival of militantism during the 1960s and 1970s with publication of his autobiography, Simple on a Soap-Box (1963), and reprints of his many other works, before his death in 1982.

Hardcase, not hardship

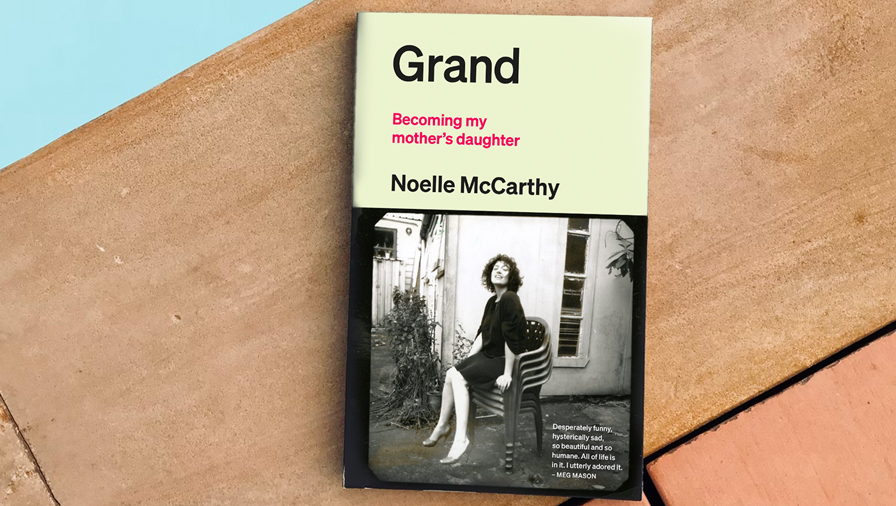

Noelle McCarthy’s Grand: Becoming my mother’s daughter is a valuable addition to this tradition, but more hardcase than hardship. It encompasses her experiences of growing up in Ireland, emigrating to New Zealand in her 20s, carving out a media career, coping with alcoholism, and becoming a mother.

The book began as a series of vignettes from McCarthy’s childhood in Cork, where her Mammy, Caroline, spent most of her days in ‘hideaway’ bars consuming the local brew, Carling.

Before her marriage, Caroline had given birth in her teens to a daughter who was adopted and a boy who died shortly after birth. McCarthy was the first born after Caroline married a plumber. Another daughter and a son followed.

Caroline wanted the best for McCarthy, sending her across town to a girls’ school for the monied class. McCarthy had little in common with her middle-class schoolmates but she was bright. She was fascinated by Bram Stoker’s Dracula, while the rest of the school was raising funds for Amnesty International or fasting for the starving in Africa.

Her father thought there were only two types of music, country and western, while her first boyfriend was into heavy metal.

No flowers for men

McCarthy’s first contact with New Zealand was working in a vegan café run by one of the Kiwis who migrated to Cork when Ireland established a tax-free residence for artists. She once tried to placate an aggrieved tax driver with some flowers McCarthy had.

This intrigued McCarthy. “Nobody Irish would send flowers to a man, let alone a taxi driver,” as it would raise a wife’s suspicions. Instead, McCarthy kept the flowers.

In 2002, after graduating from university, McCarthy decides to use her OE to check out this faraway country, quickly landing an intern’s job at the 95bFM student radio station in Auckland. She is soon in a managerial role and an on-air interviewer. In her election campaign interview with National Party leader Don Brash in September 2005, he first revealed his connection with the Exclusive Brethren.

Interviews with other leading personalities of the time, including Helen Clark, sealed McCarthy’s arrival and, at 26, she was profiled in the NZ Listener as the latest addition to National Radio.

Her success, and a brief controversy over not giving credit to the source of some commentaries, was accompanied by a binge-drinking lifestyle and a ‘party girl’ reputation. It became too much for RNZ, which dropped her as a presenter and, at 30, she was on the wagon.

Marriage, to a former professional rugby player, and a baby girl followed, but the long-distance relationship with her mother back in Cork remained as fraught as ever. These are related in a style that ranks with the best of any Irish storyteller.

“And now here’s Mammy,” she writes after her mother sees a mid-pregnancy photograph, “sticking her nose in, speculating about my body with a know-it-all tone that brings on the familiar skin-crawl of rage and intrusion. Her drunk eyes on me, trying to get into my life when she has no right to be in there. When it’s 4 o’clock in the day and she is drinking already.”

McCarthy’s writing career looks secure. Many of the vignettes stand alone as short stories (and some were previously published). One concerns a visit to a dentist for treatment to a chipped tooth. It is one of many that are threaded in a non-linear narrative that culminates in a visit to Ireland just before Mammy’s death from cancer.

The funeral is viewed online back in New Zealand, with McCarthy still coming to terms with the mother she remembers: “Mammy was like the weather in our family – changeable, primal, unavoidable.”

Grand: Becoming my mother’s daughter, by Noelle McCarthy (Penguin).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.