The ways of God’s elite business workers

ANALYSIS: Opus Dei’s influential role in banking and conservative politics.

Opus: Dark money, a secretive cult, and its mission to remake our world, by Gareth Gore.

ANALYSIS: Opus Dei’s influential role in banking and conservative politics.

Opus: Dark money, a secretive cult, and its mission to remake our world, by Gareth Gore.

You might call it the Great Reversal: a swing back to the conservative end of the political spectrum from an excessive dose of progressivism. The Covid-19 pandemic brought extreme levels of government intervention, both in the public arena and in private lives.

Economically and socially, the unintended consequences proved disastrous. Inflation returned with the lack of sound fiscal management, resulting in a worldwide drop in living standards. Prolonged shutdowns in schooling and business had detrimental health and educational outcomes.

Democratic political leaders of those pandemic times are no longer in power. The last of them, Canada’s Justin Trudeau, resigned as leader of the Liberal Party, which is likely to lose an election that must be held on or before October 20.

The Covid pendulum didn’t just affect the left. Boris Johnson was forced to resign as leader of the ruling Conservatives, who subsequently lost their substantial majority in a swing to Labour.

In Europe, spurred by cost-of-living and anti-immigration issues, voters have also favoured conservative parties in recent elections. The election in Germany on February 23 is likely to see the return of a fully pro-business government for the first time since 2013.

This conservative vibe has also been felt in business, as Wall Street and Silicon Valley adjust to a new era of Donald Trump in the White House. Major corporations such as Walmart, McDonald’s, and Ford resiled on progressive initiatives under the Biden administration. Investor Black Rock stepped back from its commitment to climate change policies that have little chance of advancing under President Trump.

Niall Ferguson, a founder of Alliance for Responsible Citizenship.

The intellectual world has also been roiled by change in which leading conservatives such as historian Niall Ferguson, his wife Ayaan Hirsi-Ali, psychologist Jordan Peterson, and US Vice-President-elect and Catholic convert JD Vance have backed a new organisation, Alliance for Responsible Citizenship.

The alliance aims to promote Christian values to “replace a sense of division and drift within conservatism, and Western society at large,” as one observer put it. It has attracted political and business support to advocate traditional social and cultural values.

It is still in its fledgling stage but has parallels in another conservative movement that also seeks to align Christian practice with real-life experience in the upper echelons of society.

Opus Dei, literally ‘the work of God’, was founded by Spanish priest Josemaría Escrivá in 1928 (who was canonised in 2002 by Pope John Paul II) as a movement for both the lay and the clergy to practice Christianity in their everyday lives. Despite its longevity and global presence, it has about 90,000 members in 60-odd countries compared with the Catholic Church’s estimated baptised of 1.4 billion.

About 70% of Opus Dei members live in their own homes, leading family lives with secular careers, while the other 30% are celibate and mostly live in Opus Dei centres.

This elitism is both its strength and weakness. Escrivá was persecuted during the Spanish Civil War (the subject of There Be Dragons, a Hollywood-style action show), and focused his recruitment on highly educated men, who were likely to reach influential positions in society.

Saint Josemaría Escrivá, founder of Opus Dei.

According to Opus, a new and critical study by financial journalist Gareth Gore, male members must still have university degrees. Women, who have been admitted since 1930, can have lesser educational qualifications, partly because they have traditionally provided domestic labour for its institutions.

Acolytes are attracted by strict codes of behaviour that are cultist in practice, which allow the movement to be labelled secretive in pursuit of its objectives. Gore, a journalist for the International Financing Review, began uncovering the extent of Opus Dei’s extensive business networks during his investigation into the collapse of Spain’s Banco Popular.

The bank once had 2000 branches in Spain alone – making it that country’s sixth largest – as well as extensive international operations. It failed on June 7, 2017, after an unsuccessful bailout plan in the wake of the global finance crisis a decade earlier. Gore discovered the 90-year-old bank had been under the control of Opus Dei members for 60 years.

“Many aspects of Banco Popular’s rise and fall simply defied logical explanations,” he writes, outside of the usual signs of mismanagement. This was revealed in the flurry of legal actions as shareholders sought to recover their investments.

One significant group of shareholders took no action to recover at least US$2 billion in losses. It was a network of funds controlled by a group of interchangeable men. Two of them were the Valls-Taberner brothers, Javier and Luis. The latter had run Banco Popular for its 50 years of expansion and was widely respected in banking circles.

Just days after his death in 2006, the board expelled Javier, who was not an Opus Dei member.

Javier Valls-Taberner turned whistleblower after being expelled from Banco Popular.

He subsequently became Gore’s major informant on how the bank had funded Opus Dei operations around the world; these included universities, university residences, business and conventional schools, publishing houses, hospitals, and technical and agricultural training centres.

All are run on a decentralised basis, in keeping with Escrivá’s plan for a movement with no chain of command, or one where responsibility can only be taken by those immediately involved. I ran across one Opus Dei operation in Vienna last year: it runs that city’s historic St Stephen’s Cathedral (Stephansdom), where Escrivá in 1955 pledged to protect all Christians under communist persecution when Austria was still under Allied occupation.

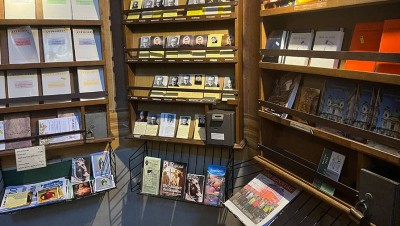

Opus Dei book display in Vienna’s St Stephen’s Cathedral.

Gore’s Banco Popular findings took him deeper into Opus Dei’s operations, particularly those in the United States, where it focused its activities on Washington DC and its political connections. These have often proved controversial, and not just because Opus Dei pushes traditional Catholic views on issues such as abortion, contraception, and euthanasia.

One involved the Soviet spy Robert Hanssen, an FBI agent who married an Opus Dei member. He confessed his espionage to her but instead of giving himself up was advised to continue with the proceeds going to Opus Dei.

Hanssen was arrested two decades later in 2001 when caught in an FBI sting. (The case was made into the 2007 movie Breach, which noted his membership of Opus Dei.)

The Washington connections proved resilient to this setback and to Dan Brown’s bestselling Vatican conspiracy thriller The Da Vinci Code, which featured a secretive society within the church.

Federalist Society president Leo Leonard.

This ability to ride out storms was due to the efforts of individuals such as Leo Leonard, a former executive vice-president of the Federalist Society, which advocates a traditionalist view of the US Constitution. Leonard was once described as the third most powerful man in the US due to his networking and fund-raising abilities to ensure conservative appointments to the Supreme Court, including those made by Presidents George W Bush and Donald Trump.

Gareth Gore.

Another example, not mentioned by Gore, is Ken Roberts, an Opus Dei member who as president of the Heritage Foundation is credited with Agenda 2025, a 900-page document said to outline Trump’s plan for America, although he denies it.

The liberal-minded Pope Francis demoted Opus Dei’s status at the Vatican, which had thrived under his more conservative predecessors. This downgrading meant the movement’s leader no longer automatically became a bishop.

“The Pope’s decree made it clear that he supported Opus Dei’s fundamental mission to spread holiness in the world through the sanctification of work – but also hinted that the movement had strayed from that mission,” Gore concludes.

He takes an adversarial approach in a 440-page book, backed up by more than 100 pages of research notes and an index. It’s a fascinating read about how those successful in business can pursue private agendas that affect the wider public. Just like any other lobby group, whether secular or religious, they use the best people they can find.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.