The two men who created artificial intelligence

How corporate giants gained control of the world’s most controversial technology.

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the race that will change the world, by Parmy Olson.

How corporate giants gained control of the world’s most controversial technology.

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the race that will change the world, by Parmy Olson.

Big-tech share prices have not yet fully recovered from the news last December that China had developed a low-cost form of artificial intelligence (AI). Yet little is known about DeepSeek’s open-source model.

Meanwhile, in their efforts to remain the dominant AI companies, Microsoft has committed U$80 billion ($140.5b) to build data centres this year, while rival Alphabet (parent of Google) is not far behind, with planned spending of US$75b.

Nvidia, the chip maker that makes AI’s enormous processing power possible, initially lost nearly US$600b in market value due to DeepSeek, with its shares plummeting by as much as 18%. But it remains a US$3.3 trillion company.

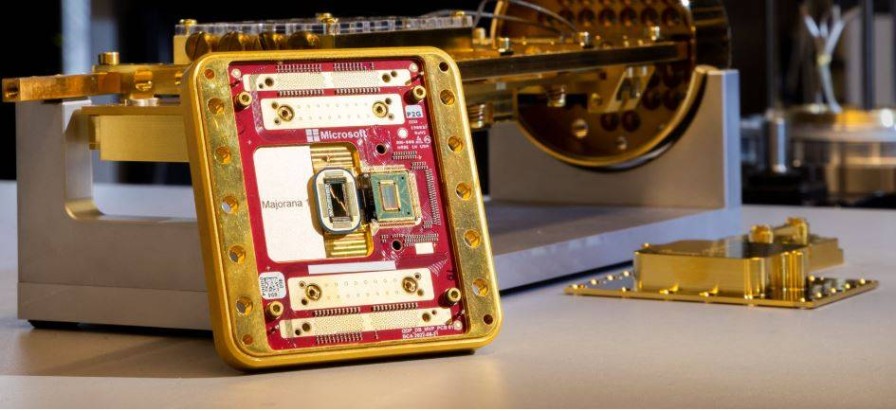

Microsoft’s new Majorana quantum chip.

In the past week, the Financial Times reported Microsoft had made a major advance in quantum computing that would enable it to build a practical model by the end of the decade. The breakthrough is the first in a 20-year effort to confirm the existence of a fourth state of matter, particles known as the Majorana fermions, alongside solids, liquids, and gases.

They were first theorised in 1937, though scientists have struggled to demonstrate they actually exist. Without getting too technical, Microsoft had bet these particles offered the best route to overcoming the biggest obstacle to building a practical quantum machine.

Instead of using the ones and noughts in conventional computing, the quantum bit (qubit) can represent both at once, and any state in between. The result is that quantum computing can process vastly more information, simultaneously.

Parmy Olson.

Which bring us back to AI and Parmy Olson’s Supremacy, which was published in the US late last year and won the Financial Times-Schroders best business book of the year. The text was closed off in March 2024, so it does not contain any references to DeepSeek or recent developments, such as Mira Murati launching her own AI startup, reported in the same issue of the Financial Times quoted earlier.

Murati is mentioned in Supremacy in her then capacity as head of research and product development at OpenAI, one of the two companies at the centre of Olson’s historical account.

Olson is a columnist at Bloomberg Opinion and covered AI developments for the past 13 years at the Wall Street Journal and Forbes. Her familiarity with the territory is matched by her journalistic ability to tell a story without jargon and obfuscation.

Her focus is on the personalities, notably the two men who have dominated the industry since its modern inception in 2010, though the term ‘artificial intelligence’ was first coined to describe ‘thinking machines’ at a Dartmouth College, Massachusetts, workshop in 1956.

They are Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis, respectively described at the startup guru from St Louis, Missouri, and the chess geek from North London. Like Bill Gates, whose autobiography of his early years was reviewed here a few weeks ago, they both showed early signs of genius.

OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman.

Altman, a gay vegetarian since his teens, grew up in a mid-west Jewish family and was educated at an elite high school before going to Stanford University. The founders of Google, Cisco, and Yahoo also went there. His geekish interests were reflected in his ability at poker (Gates was also a card player) and he launched his first startup, Loopt, in 2005 at age 19.

It failed to gain traction but was sold for US$43.4 million. Six years later, he was running Y Combinator, an accelerator fund that launched Airbnb and Dropbox. In 2015, he co-founded OpenAI with Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, among others.

Hassabis was born to a Cypriot father and Singaporean mother. His early mathematical talent was reflected in chess – he was the world’s second-best under 14 – and simulation games. One had sales of 15 million before he went to Cambridge University. His AI venture, DeepMind, was founded in 2010 with New Zealander Shane Legg and Mustafa Suleyman. Last year, Hassabis received the Nobel Prize for chemistry for his work on proteins.

DeepMind co-founder Demis Hassabis.

London lacked the depth or long-term horizon of Silicon Valley’s venture capitalists to fund Hassabis’s ambitions. Legg provided the link through his friendship with Thiel, a New Zealand citizen. “We needed someone crazy enough to fund an AGI [artificial general intelligence] company … [and] who had the resources to not sweat a few million and liked super-ambitious stuff,” Legg told the author.

Thiel, also a chess player and contrarian with right-wing views, kicked in an initial £1.4m but the DeepMind operation stayed in London, where it remains and will move into Google’s stunning new headquarters near King’s Cross Station. While Altman’s AI quest was built on games simulation, Hassabis initially based his on biological functions of the brain. Progress was slow until neural networks proved more efficient for large-scale, deep-learning models.

Google DeepMind will be based at new London headquarters due for completion in 2025.

This was an area that also interested Google, which made its first approach to buy DeepMind in 2013. Hassabis, like Altman, did not want to become part of corporate big tech. But, eventually, both needed substantial capital for their voracious computers and the stratospheric salaries to attract the best researchers, who included professors from the world’s best universities.

Olson is at her best as she tracks the fortunes of these two companies in their struggle for scientific dominance amid the machinations of big tech and its ability to raise billions of dollars in the blink of an eye.

“AI’s mind-bending potential gave it an almost religious attraction to people with strong beliefs about how it should be used,” she observes at this point in the AI story. “Over the next few years, these ideological forces would collide with the innovators and the corporate monopolies who were battling to control AGI, becoming an unpredictable hazard …”

Cutting a long story short, these would later involve Altman temporarily being pushed out of OpenAI in November 2023 by a board set up as part of its “strategic partnership” with Microsoft in 2019 to allay fears about misuse of AI.

Microsoft had become the chief financial backer of OpenAI in place of Musk and Thiel but had no direct equity or control. That changed with the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, which became an instant public success on its release and made AI a household word. It had 30 million users within two months.

Microsoft Satya Nadella.

Microsoft chief executive Satya Nadella had to move quickly to resolve the fiasco of Altman’s sacking and effectively brought OpenAI under more direct corporate control. Nadella invited Altman to join Microsoft, and he was soon back in the top job at OpenAI.

No-one was more surprised at the success of ChatGPT than Google, which had for years developed similar tools but was too afraid to release them for fear of its effect on its search engine advertising revenue, which runs at US$260b a year.

In the panic to respond, Google came up with Bard and put AI to use at YouTube and Gmail. Microsoft had hoped its Bing search engine, combined with AI-powered Copilot, would break Google’s dominance over search, but it was not to be. Bing remained with a market share of about 5% to Google’s 95%.

Meanwhile, Google was able to draw on its huge storage bank of innovation: the deep-learning architecture transformers; the large-language LaMDA introduced as Meena in 2020; and DeepMind’s five-year lead on OpenAI. Hassabis had developed AI systems that could beat humans at chess and Go. But OpenAI could write emails, which was more impressive to the average computer user.

“Hassabis had sought to build AGI through games and simulations and measured the success … through awards and the prestige of publishing papers in scientific journals,” Olson notes. By contrast, Open AI’s approach was “driven by engineering principles and scaling existing technology as much as possible”.

DeepMind co-founder Shane Legg.

Google merged DeepMind with GoogleBrain and produced Gemini, a souped-up version of Bard. Hassabis was put in charge, prompting Legg to tell Olson: “Instead of becoming a bit more independent, we became integral to Google itself.”

The rivalry had turned full circle, with both OpenAI and DeepMind becoming essential to the growth of two of the world’s most valuable companies and the controversies surrounding a technology that had yet to find a publicly acceptable balance between the profit motive and social benefit.

The rest of this story has yet to unfold. If you want to know more about the future, it pays to learn more about the past. That applies to AI, and Supremacy is a good place to start.

Last year’s Nobel Prize-winning economist Daron Acemoglu attended the recent AI Action Summit in Paris. His verdict: “AI could invigorate this [prosperity] trend by complementing human skills, talents, and knowledge, improving our decision-making, experimentation, and applications of useful knowledge…

“Yet … AI also represents one of the gravest threats that humanity has ever faced … It may even destroy democracy and human civilisation as we know it.”

That should be argument enough to become more aware of what Altman and Hassabis had done and where they are taking us.

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the race that will change the world, by Parmy Olson (St Martin’s Press (US)/Macmillan Business (UK)).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.