The talented Mr Lee: China’s proliferation pirate

German media hunt for the FBI’s most wanted arms dealer.

The Chinese Phantom: The hunt for the world’s most dangerous arms dealer.

German media hunt for the FBI’s most wanted arms dealer.

The Chinese Phantom: The hunt for the world’s most dangerous arms dealer.

The use of highly accurate ballistic missiles and weaponised drones changed the nature of conflict in the first major outbreak in Europe since 1945.

The Russo-Ukraine war is in its third calendar year, with neither side achieving air superiority, the usual route to victory. Russia was expected to seize control of contested airspace early in the conflict.

But it didn’t happen. To everyone’s surprise, Ukraine, despite reluctance on the part of its allies, was able to employ air defences that repelled and deterred Russian aircraft. This forced both sides to rely more heavily on standoff weapons, including long-range artillery, missiles, and drones.

A bigger surprise was that, as older conventional missiles ran out on the Russian side, the suppliers of new drone and rocket technologies were Iran and North Korea – countries sanctioned by the UN under nuclear proliferation resolutions endorsed by Russia and China as members of the Security Council.

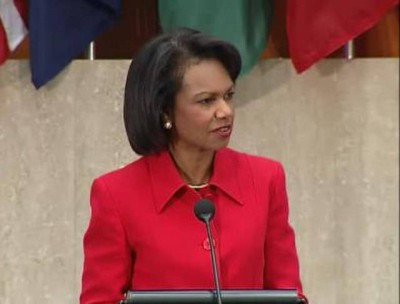

US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2007.

In 2006, then US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was working with China on anti-terrorism measures, which meant supporting UN embargoes of arms to Somalia and a peace mission to patrol the border between Israel and Syria.

The same year, US intelligence agencies noticed a Chinese national was selling materials to Iran that contributed to its nuclear rocket programme. Initially, these were carbon fibres and certain specifications of aluminium. The trade also included items such as gyro sensors that kept rockets on course, a technology first invented by Nazi Germany.

The Chinese trader was Karl Lee, also known as Li Fangwei. He is the subject of The Chinese Phantom, the fullest account to date of a weapons trader who dominated the flow of sanctioned materials to Iran’s missile programme until at least 2014.

The book is the outcome of research by four German journalists. Two of them, Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer, won Pulitzer Prizes for their work at Süddeutsche Zeitung on the Panama Papers. Christoph Giesen is China correspondent for Der Spiegel, while Philipp Grüll works for public broadcaster ARD.

Publication in German last year was accompanied by a Deutsche Welle documentary, Wanted: The World’s Most Dangerous Arms Dealer. Though Lee’s activities have been well documented and known to the world’s intelligence agencies, he has never been arrested despite a US$5 million ($8m) bounty by the FBI.

The same amount led to the capture and execution of Al Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden and the arrest of Mexican drug lord Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman.

Lee’s activities first came to public attention in 2009 when New York County (Manhattan) district attorney Robert Morgenthau laid a 59-page, 118 indictment sheet that identified a long list of front names and aliases used by Lee and his worldwide network of companies. This originally come from Israel’s Mossad, which was tracking Iran’s programme to build ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear bombs to eliminate the Jewish state.

The legal action was triggered by one of Lee’s associates in South Africa mistakenly putting a transaction through Citibank, thus breaching US financial sanctions. The charges sought Lee’s extradition from his base at Dalian, a major seaport in northeastern China.

While the case attracted the attention of the world’s leading media outlets, China took no action against Lee. Further pressure was applied by the FBI, who posted the bounty in 2014. Not long after, a mystery website appeared. Whoisleefangei.com showcased Lee’s activities in a sophisticated and provocative manner in Chinese, English, and Arabic versions.

The Newsweek cover story on Karl Lee, aka Li Fangwei.

Four years later, the Trump administration revived the campaign to stop Lee through a Newsweek article by veteran spywatcher Jeff Stein. But – despite Iran’s constant missile attacks against Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Syria at that time – still nothing happened to curb Lee.

Suddenly, he was no longer an issue. The provocateur-style website disappeared. The German media team picked up the now-dead trail in 2019 after a tipoff from a former FBI analyst. He told them about the continuing illegal sale of electronic measuring and navigation instruments to Iran. Its missiles had become “more effective, more precise, and more lethal with every passing year,” the informant said.

Then and now, these pose an existential threat to Israel. They are also supplied to Iranian surrogate terrorist organisations, such as Hamas, Hezbollah, and Houthis in Gaza, Lebanon, and Yemen. Targets have included US bases, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Iraq.

Already, the Germans’ investigations into Lee had the features of Fantômas, the fictional French supervillain who always managed to escape just as he was about to be caught. Iran was the “evil state” – compensating its lack of air power by building up vast arsenals of rockets and sharing them with its likeminded acolytes.

Christoph Giesen, Der Spiegel’s China correspondent.

The journalists searched the Panama Papers, first released in 2015, throwing up references to Lee and his network’s links to the infamous law firm Mossack Fonseca. Giesen, the Der Spiegel correspondent in China, visited Dalian in the hope of finding Lee at one of his many addresses and businesses.

Earlier, he and a cameraman had been to Lee’s birthplace at Gannan, in China’s most northeastern province, Heilonjiang, bordering Russia. Their door-knocking revealed the underbelly of Chinese businesses that don’t have CBD offices or fancy factories. The nominal HQ of Lee’s empire was a floor of apartments.

But the trips down various rabbit holes did uncover some important discoveries. One was the original LIMMT (Dalian) Metallurgy and Mineral Company, which Lee had his father set up in 1998, long before the Iran sanctions came into force. It had closed in 2012.

Another find was a sprawling, rundown graphite factory owned by Sinotech (Dalian) Carbon & Graphite Manufacturing Corporation. This was founded in June 2006 and owned by Lee and his younger brother. Although it had stacks of graphite, Giesen was told exports had ceased.

That foray, before the Covid shutdown, didn’t reveal the whereabouts of Lee, who remains a non-person, as least to everyone who had previously been interested in him, notably Mossad and the US intelligence agencies.

A German authority on China, Angela Stanzel, provides the bigger picture of Chinese motives. Although China backed UN sanctions in 2006 to prevent Iran’s nuclear weapons programme, it did not stop Chinese companies from doing business there. From 2003 to 2019, trade between the two countries increased nine-fold as Western companies departed.

Two principles underpin Chinese foreign policy, according to Stanzel: territorial integrity and non-intervention. Regarding Iran, this means no Chinese involvement in regional disputes such as the Middle East.

But Chinese companies benefit from the second principle: “what counts are business, deals, and dodgy arrangements,” the authors state. In practice, this means the Chinese Government denies it has anything to do with Lee.

The same logic applies to China’s dealings with Russia and North Korea, as well as Israel, which – the authors discover late in the piece – remains the main enemy of Iran but is also a key recipient of Chinese investment in Israel’s infrastructure and startup sector.

Despite his Fantômas escapes, Lee has not been completely forgotten. A 2023 US Department of Justice indictment, not mentioned in the book, targets an associate, Chinese national Xiangjiang Qiao, who also goes by the alias Joe Hansen. He is charged with supplying Iran’s missile programme and faces nine counts related to sanctions evasion, money laundering, and bank fraud.

Qiao is allegedly an employee of the Lee-owned Sinotech company and the indictment states that, for more than three years – from at least March 2019 until September 2022 – he was involved in supplying Iran with isostatic graphite.

This is a dense, fine-grained graphite, whose production requires a special type of machinery called a cold isostatic press. Isostatic graphites have exceptionally high thermal and chemical resistance, making them excellent materials for solid rocket motor nozzles and missile re-entry vehicle nose tips.

The English-language version of the documentary has been widely viewed on You Tube (9.6 million views as at June 20). Both the book and the documentary assert Lee’s network continues to operate without his active involvement.

As for Lee’s whereabouts, most sources point to his detention, the recent fate of other prominent Chinese businessmen. No official evidence confirms this. A brief statement in Chinese on Wikipedia alleging his arrest in 2019 was removed soon after it was posted.

The authors’ journey took them to the US and China as well as through Austria, the UK, and Israel. The book has a comprehensive list of published sources, as well as acknowledging dozens of human contacts.

The conclusion that China plays on both sides of Middle East conflicts, while the US and Israel hold back on Lee to maintain engagement with China, has the whiff of realpolitik in a parallel world of deceit and lies. The final chapter has yet to be written, but the price paid by its victims continues to mount.

The Chinese Phantom: The hunt for the world’s most dangerous arms dealer, by Christoph Giesen, Philipp Grüll, Frederick Obermaier, and Bastian Obermayer. Translation by Simon Pare. (Scribe). Available September 3.

See also: Wanted: The world’s most dangerous arms dealer onYou Tube/Deutsche Welle.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.