The seeds of dictatorship lie in public acclaim

An expert on Chinese communism shows how personality cults are cultivated.

An expert on Chinese communism shows how personality cults are cultivated.

The ignominious end of the Trump administration has been likened to the overthrow of a fascist dictatorship and the restoration of democracy.

This is a distortion of actual events, the implications for the future and whether the American Constitution has reached its use-by date.

President Donald Trump may have had authoritarian traits, a narcissistic personality and a tendency to dispose of his political enemies. But throughout his term he faced one of the strongest lineups of opposition to his rule than any other president.

This comprised constant scrutiny by the media and a Democratic Party that twice engaged the impeachment process - a first in American history.

As Trump himself said, his watch was accompanied by what he called a continuous witch-hunt. This is a far cry from his contemporaries in countries where democracy is just a figment of legality and dictatorial power is exercised by a single leader.

Trump may have wanted to cling to power by whatever means, but his eventual fate does not equate with that of Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein or Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe.

It is commonly accepted that dictatorships over the past two decades have become entrenched in major countries such as China, Russia and Turkey as well Syria, Venezuela and Belarus.

In Africa, The Economist last week reported that several leaders have overturned term limits and extended their regimes. They include Uganda, Togo, Equatorial Africa, Cameroon and Gabon. (The post-colonial grab for power by tribal leaders is the subject of its own book, Dictatorland, by Paul Kenyon, (2018).)

In Asia, Covid-19 has provided an opportunity for democratically elected governments such as India’s and Malaysia’s to seize extra powers and suppress dissent, while one-party states are still the rule throughout the Arab world, parts of Latin America and even Europe, where President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus could be the next to depart.

Murderous history

The 21st century is a mild period compared with the previous century, when dictatorships were murderous and responsible for tens, if not hundreds, of millions of deaths.

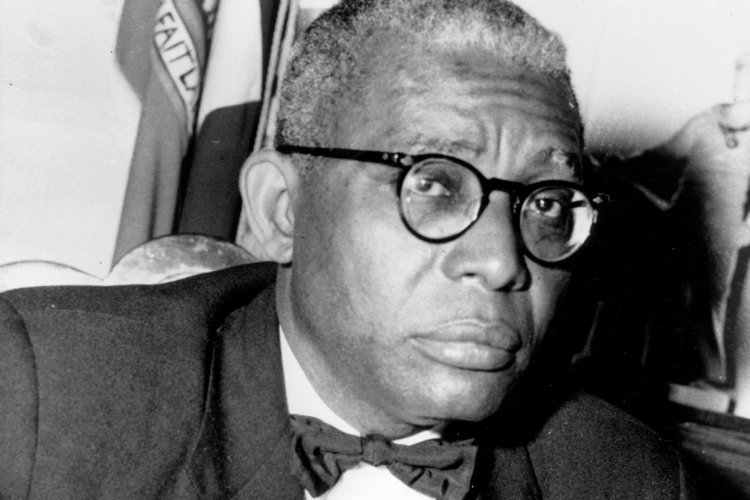

Dutch-born and Hong Kong-based historian Frank Dikötter has profiled eight examples in How to be a Dictator, a study of the five most notorious – Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao and Kim Il-Sung – and three lesser examples – Ceaușescu, Mengistu of Ethiopia and 'Papa Doc' Duvalier of Haiti.

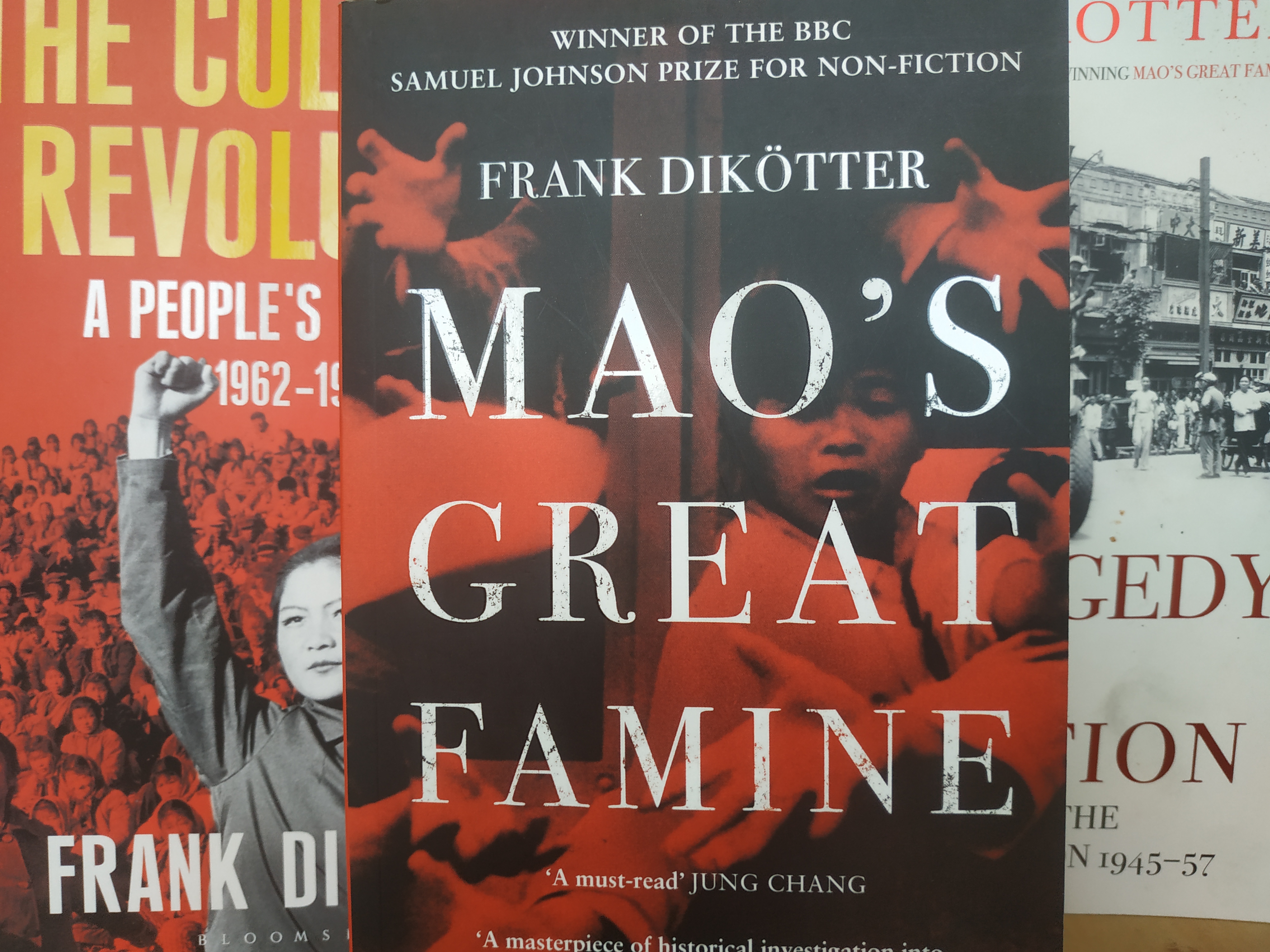

Dikötter’s reputation is second to none, based on his trilogy about the appalling human cost of Chinese communism under Mao Zedong from 1945-76.

In 2014, Dikötter spoke at the Auckland Writers Festival about how he was able to research Chinese archives with little interference in the years after that country opened to the world under Deng Xiaoping. The books were published in 2010, 2013 and 2016 though not in chronological order. China may regret that access now but, as far as I know, Dikötter is still a professor at the University of Hong Kong.

His profiles run to about 30 pages and show how each dictator was able to build up his power and then use it against against any threat.

“A dictator must instil fear in his people, but if he can compel them to acclaim him he will probably survive longer,” Dikötter writes.

Creating a cause

Personality cults are the common denominator to achieving this end. It means selecting an ideology that destroys the kind of individualism that developed in Europe after the Enlightenment.

It can be based on a religion, a closed political system such as socialism or fascism, or racial exclusivity based on tribal or kinship ties.

The task then is to make everyone buy into the lie.

“When everyone lied, no one knew who was lying, making it more difficult to find accomplices and organise a coup.”

Mussolini, a journalist, was the first to use control of the media to boost his personality cult over his 23-year regime, which ended with him being hunted down by partisans.

Stalin and Mao both died of natural causes after lasting 31 and 27 years, respectively. A satirical movie, The Death of Stalin, underlined a point made by Dikötter that medical help was late to the scene “as the leader’s entourage was petrified of making the wrong call.”

This analysis shows a dictatorship is far more insidious than any coup attempted by Trump’s supporters in full public glaze.

A dictator’s success can be measured by whether his grip on power can be passed to the next generation, as it has three times by the Kims in North Korea and twice by the Duvaliers in Haiti. The personality cult in North Korea is the most extreme and is based on a deified mythology that shows little sign of collapsing.

China’s Xi Jinping is heading in the same direction with The Atlantic, among others, reporting his “thought” now takes priority over other ideologies and is imposing greater state control over all businesses as well as individuals.

Since being elected general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, Xi has purged thousands of potential rivals, extended his term as chairman or leader to life, and launched an aggressive campaign against any opposition inside and outside the country.

Sticky end

Mostly, dictators come to a sticky end because they are too paranoid to have a succession plan. They also put too much trust in their own myths. As Dikötter tells it, dictators must capture the souls of their captives and mould their thinking as if by a spell.

“But there never was a spell. There was fear, and when it evaporated the entire edifice collapsed,” he writes.

Ceaușescu and his equally reviled wife Elena were executed to wide public acclaim after a speech to a mass demonstration outside Communist Party headquarters in late December 1989 went badly wrong – a lesson, perhaps, for Lukashenko of Belarus and even Vladimir Putin in Russia. When enough dissent surfaces, and it cannot be suppressed, public fear dissipates.

Mengistu, another communist in the Stalinist tradition, had to flee to exile in Zimbabwe after an insurrection. His regime collapsed overnight, leaving a legacy of devastation caused by war, famine and collectivisation that still lingers in much of the rest of Africa, where dictators outnumber democratically elected leaders.

Dikötter’s conclusions are largely positive: that freedom will eventually triumph, though some dictatorships are making a comeback. In Syria, Bashar al-Assad has had to devastate his country to keep his father’s legacy in tact.

Turkey’s Recip Sayyid Erdoğan is a textbook example of how to accumulate dictatorial powers after he was democratically elected in 2014. He used an attempted coup two years later to clamp on all potential opposition, whether in the public service, military or the private sector, jailing thousands of judges, generals, journalists and teachers.

How to be a Dictator: The cult of personality in the 20th century, by Frank Dikötter (Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.