The rise of the diplomats

How an elite of public servants moulded foreign policy over eight decades.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

How an elite of public servants moulded foreign policy over eight decades.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s high-profile global diplomacy in recent weeks prompted some to perceive fundamental changes in foreign policy. These were based on her invitation to the Nato summit in Madrid, forgoing the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Rwanda, the signing of a free market deal with the European Union, another mission to Australia, and attendance at the past week’s Pacific Forum.

This level of activity was to be expected after a two-year hiatus, during which New Zealand was closed to the world. The commentary suggested a change in emphasis, with closer military and political ties to the US and Western allies to resist Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and a more critical stance toward China for its backing of Russia and growing influence in the Pacific.

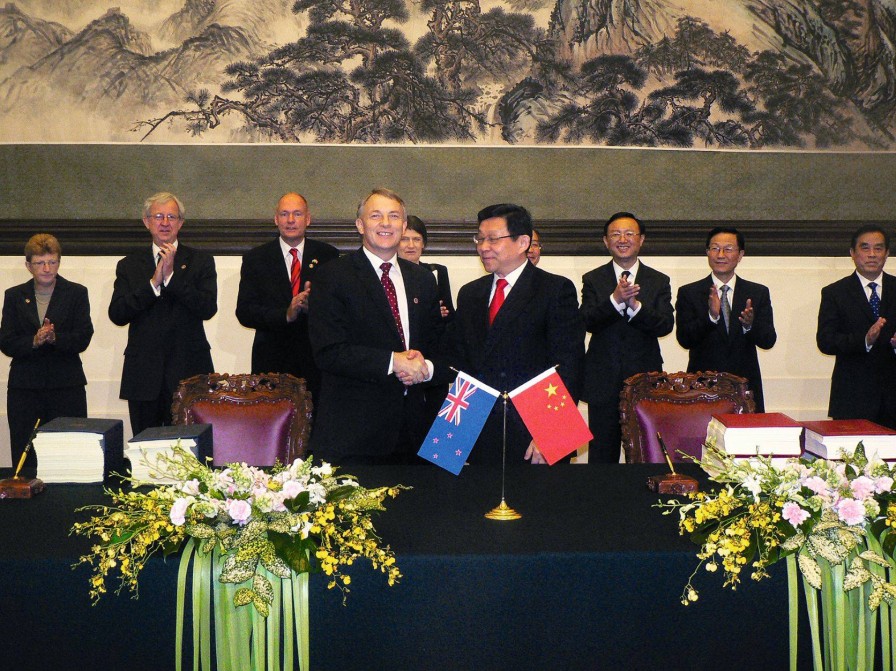

Foreign Affairs Minister Phil Goff signs the China FTA in Beijing. PM Helen Clark is looking over his shoulder. Photo: MFAT.

Attitudes hardened toward the UN’s failure to condemn the Ukraine invasion and the use of the Security Council’s veto by Russia and China to ensure this outcome.

Among the academic commentators, Otago’s Professor Robert Patman and Victoria’s Geoffrey Miller have offered insights. Miller explains Ardern’s apparent embrace of a pro-Western stance despite her rejection of an ideologically polarised world between the democracies and authoritarian states.

He likened her brief speech at Madrid to David Lange’s foreign policy of the 1980s, when the anti-nuclear stance turned off allies such as the US and UK. Now that Nato was widening its European remit to include security threats from China, Miller noted Ardern’s lack of direct references in a separate speech at Chatham House, a London think tank.

China buys a third of New Zealand’s exports, including dairy and meat that has limited access to US and European markets, meaning Ardern has no reason to hope its military support for the West will be repaid in economic benefits.

No change

Patman sees no change in New Zealand’s strategy of supporting the West against authoritarian states that flagrantly breach an international rules-based order, while also rejecting “the view that any great power should enjoy exceptional rights and privileges in the 21st century”. Defeat of Putin was critical, as it would curb any Chinese plans to annex Taiwan.

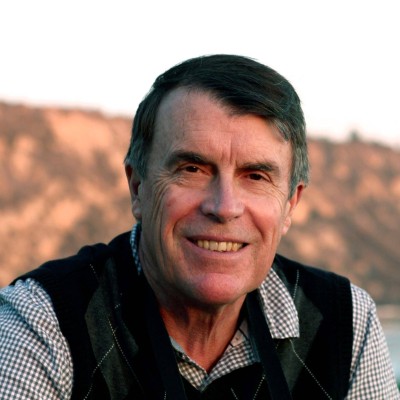

Ian McGibbon has a 40-year career as a public historian. Photo: MUP.

None of these issues is new but historical context is available in New Zealand’s Foreign Service: A History, a 570-page volume edited by Ian McGibbon, who has written some 20 books on diplomatic and military topics.

A key issue is the role of prime ministers in foreign policy. From its origins in 1943, this was handled by the prime minister’s office, now the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. In those days, foreign policy was known as ‘external affairs’ and performed by a handful of officials.

They were small fry compared with the rest of the public service but compensated by being smarter and more influential. Until the 1980s, it was standard practice for Labour prime ministers, from Peter Fraser onward, to have the external affairs portfolio.

After 1945, this involved the building of post-war global institutions, including the UN. Notably, New Zealand opposed a Security Council veto for the five victorious world powers. The National government, elected in 1949 under Sir Sidney Holland, had less interest in the international scene, though that changed under Sir Keith Holyoake, who continued the tradition.

Holland closed three of the then eight diplomatic posts established by Fraser. The most notable was Moscow, where a legation had opened during wartime. Labour restored it as an embassy in 1973.

Soviet agents

The staff of six in the late 1940s had four communist sympathisers, all of whom were later forced out of the foreign service as the Cold War intensified and agents recruited by the Soviet Union were exposed. The best known, Paddy Costello, was the service’s most accomplished linguist. He went to an academic post in England.

WB Sutch was first suspected as a Soviet agent while representing New Zealand on the UN’s Economic and Social Council in New York from 1947-50. He was personally investigated by Sir Alister McIntosh, the Secretary of External Affairs, at Fraser’s request.

McIntosh admired Sutch and hoped he would get a post outside the service on his return to Wellington. Later, despite the suspicions, Sutch was appointed head of the Department of Industries and Commerce under the Nash government in 1958.

McGibbon, who writes the chapters covering the period until McIntosh’s retirement in 1965, outlines budget cuts under both Holland and Labour’s Walter Nash, prime minister from 1957-60. The latter is described as indecisive, failing to make many appointments, while his parsimony was even greater than Holland’s.

Public support

Politicians relied on public support for their concerns about the cost of a foreign service. Yet, as McGibbon tells it, New Zealand diplomats had a reputation overseas as freeloaders, who seldom repaid the hospitality they enjoyed from others.

McGibbon’s account is bolstered by access to McIntosh’s papers, among others, giving fresh insights into New Zealand’s attitudes to significant events such as the partition of Palestine, the Korean War, and the Anglo-French-Israeli seizure of the Suez Canal. The opinions of officials often clashed with those of politicians, who held pro-British sympathies long after the diplomats had moved on to supporting US views.

By 1963, the Department of External Affairs had risen in status and power as New Zealand grappled with the implications of the UK joining the European Common Market and negotiated the Nafta with Australia. The department, which became a ministry in 1970, then had a staff of 260 compared with 30 in the PM’s office.

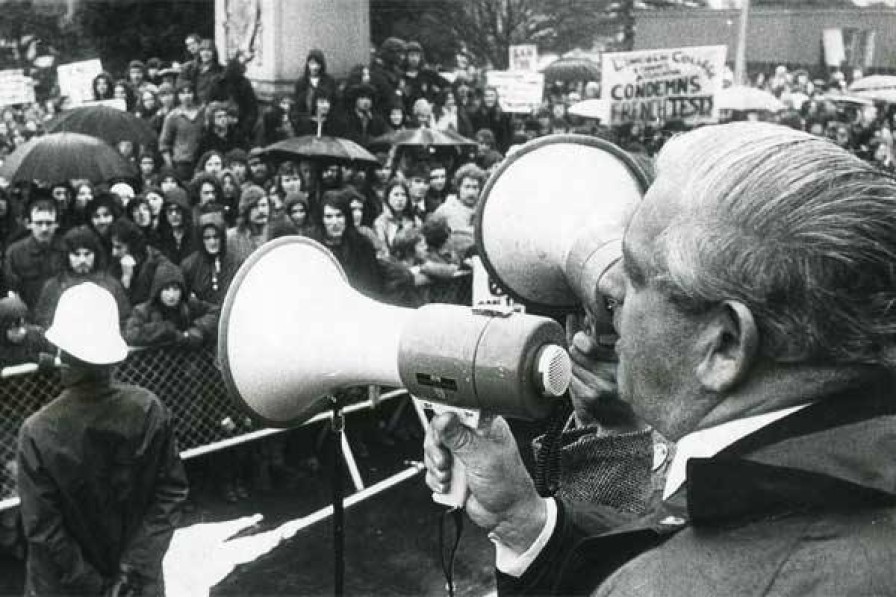

Norman Kirk’s election to power was partly based on foreign policy issues.

The political pendulum moved again with the election of Norman Kirk in 1972. Labour Party members were fired up by opposition to the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, and nuclear weapons. Foreign policy was, and still is, a strong motivating force on the anti-capitalist Left. The department was under pressure to change direction. Major milestones included the recognition of communist China and a show of military force against French testing in the Pacific.

McGibbon discloses that Frank Corner, a senior diplomat who headed both external affairs and the PM’s office until their separation in 1975, had suggested such an action years earlier. It had been rejected but was taken up enthusiastically by the Kirk government.

David Lange with rugby officials when African nations threatened sports boycotts. Chris Laidlaw, at left, headed a short-lived embassy at Harare, Zimbabwe. Photo: Ian McGibbon.

Elite ‘mandarins’

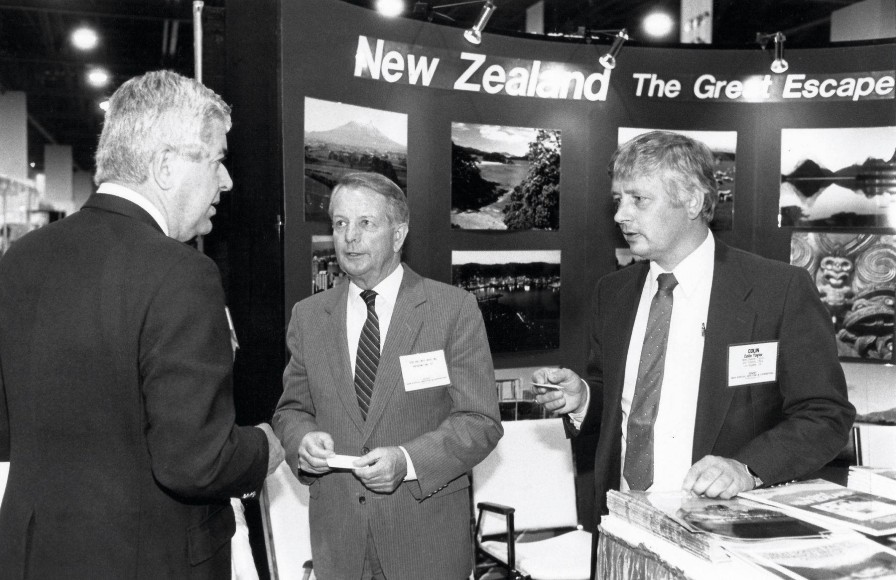

The 1980s found the diplomats at odds with Sir Robert Muldoon and Lange, both populists who considered the service as elitist ‘mandarins’. The habit of politicians denigrating the foreign service did not stop them from using it to reward their kind. Prime Ministers such as Sir Wallace (Bill) Rowling and Jim Bolger became ambassadors or high commissioners and the practice continues to this day. A talented exception was Mike Moore becoming head of the World Trade Organisation.

Bill Rowling was among prime ministers who accepted diplomatic posts. Here he is at a promotional pavilion in the US. Photo: Ian McGibbon.

Despite these differences, the ministry thrived as overseas posts extended to all points of the globe, often without sufficient economic benefits to justify them. The name underwent a further change, after absorbing the trade commissioner network from the quasi-autonomous NZ Trade and Enterprise in 1988.

Meanwhile, the service had been kept busy by the Rainbow Warrior sinking, in which the French used a threatened trade boycott to free the agents responsible; the Fiji coups that toppled a democratic government; and sporting boycotts from African nations over New Zealand’s rugby ties with South Africa.

Incident-filled chapters on these and many other events are contributed by Diana Morrow, Steven Loveridge, and Hamish McDougall. In his account of the efforts put into gaining access for primary commodities into protected economies, McDougall observes this could have been at the expense of broadening or deepening other diplomatic ties.

Joanna Spratt and Anita Parkins describe the past three decades as the service reaching maturity, with no formal ties to the PM’s office or even having a prime minister in control of the portfolio, though Helen Clark had a long-standing interest in foreign policy.

New Zealand's Foreign Service, edited by Ian McGibbon. Publishing date: August 11.

Expanding footprint

The 9/11 attacks and spread of terrorism ensured the diplomatic world remained in turmoil but it was New Zealand’s economic prosperity in this century that enabled the ministry to keep expanding its footprint, particularly when Winston Peters, in two coalition terms with Labour, used his MMP leverage to extract bigger budgets. His first term as minister (2005-08) was outside the Cabinet, the first time the ministry had no direct access to the top decision-makers.

Harder times came in 2008 with National’s minister, Murray McCully, who was angry at a vote against Israel at the UN in defiance of the new government’s policy. He then unleashed what Spratt describes as a “revolution” under John Allen, its first outside chief executive.

The effort to change a culture variously described as “overly hierarchical,” that “stifled innovation” and was “risk averse” proved a disaster, with fears a fifth of its staff would lose their jobs in a reshuffle. Ten years later, and three years after Allen’s departure, MFAT employed nearly 1700, half of them in 60 overseas posts.

Perkins’ objective view contrasts with retired diplomat Peter Hamilton’s account published last year. Both reveal the depth of resistance to proposals for business-friendly outsiders and management changes. Hamilton described efforts to find the source of leaks to the Labour opposition and former Foreign Affairs Minister Phil Goff as a ‘witchhunt’.

McGibbon injects sober assessments on staff issues to balance Perkins’ thematic chapters on extensive trade agreements, troubleshooting in East Timor, Bougainville and Afghanistan, and much more. She notes the “meagre results” from many of these efforts, including two stints on the Security Council, but concludes that New Zealand remained consistent in its approach to being a “good global citizen”.

Overall, much is revealed about the Foreign Service’s meritocratic culture, its ‘rotational’ policy on overseas postings, and the punishing effects on family life. Today, the ministry is a behemoth that also has to cater for racial diversity and gender balance. This is an official history that benefits from its extensive accounts of the contribution by many individuals, and their families, who spent their careers representing their country.

New Zealand’s Foreign Service: A History, edited by Ian McGibbon (Massey University Press).

Related reading:

New Moons for Sam, Peter Hamilton (2021)

Balancing Acts, Gerard McGhie (2017)

Diplomatic Ladies, Joanna Woods (2013)

Agents Abroad: The New Zealand Trade Commissioner Service (2009)

Against the Odds, Ted Woodfield (2008)

Standing Upright Here, Malcolm Templeton (2006)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.