The resurrection of Salman Rushdie

Autobiography doubles down on his public and private lives.

Knife: Meditations after an attempted murder, by Salman Rushdie.

Autobiography doubles down on his public and private lives.

Knife: Meditations after an attempted murder, by Salman Rushdie.

When Sir Salman Rushdie realised he had a second chance at life, after a near fatal stabbing, he decided he would double down on perceptions of his twin identities.

Rushdie was attacked by a knife-wielding Lebanese-American, then 24, who was fulfilling a fatwa ordered by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei. Rushdie was to speak in a 4000-seat auditorium on behalf of the Chautauqua Institute, which provides asylum for writers under threat.

Rushdie had lived 33 years in fear of his life, moving from London where he had complete police protection to New York, where he felt relatively safe. (London police said they foiled six attempts.)

That changed on August 12, 2022, when before he had even started his speech, he glimpsed a “running man”, who had leaped out of the audience. “I see each step of his headlong run. I watch myself coming to my feet and turning toward him … I raise my left hand in self-defence. He plunges the knife into it.”

That is a quote from the beginning of Knife: Meditations after an attempted murder, Rushdie’s long-anticipated first-hand account. It will be one of this year’s most read books and is certainly much more accessible than his gargantuan novels. That latest, Victory City, was completed before the attack.

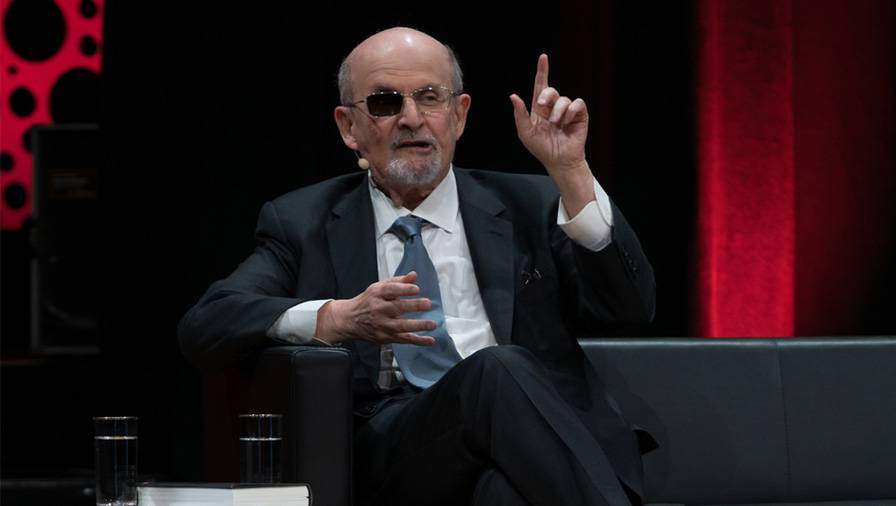

Sir Salman Rushdie in 2023.

The double-identity issue had dogged Rushdie since the 1989 fatwa was declared after publication of The Satanic Verses. He cites examples of other writers whose public and private selves were different, if not divisive.

Gunther Grass had first told Rushdie about the phenomenon of the private Gunther and the public Grass; Graham Greene was said to have had an alter ego who impersonated him.

“I too am ‘Salman’ and ‘Rushdie’. There is a demon Rushdie invented by, I have to say, many Muslims – this is the Rushdie the A [his term for the attacker] believed he wanted to kill.

“There is the arrogant, egotistical Rushdie created by the British tabloids … the party-animal Rushdie. And now, post August 12, there is a more, sympathetically imagined ‘good Rushdie’, the near-martyr, the free-speech icon…”

Then there is the “Salman sitting at home, the husband of his wife, the father of his sons, the friend of his friends, trying to get over what happened to him, still trying to write his books.”

Not surprisingly, Knife is mainly about the ‘Salman’ persona – his five years of happy marriage to African American poet, photographer, and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths, on whom he lavishes praise that would not be out of place in a romance story; his London-based sister Sameen and his grown-up boys from previous marriages; and close friends such as his literary agent and other writers.

Sadly, two of them, Martin Amis and Paul Auster, had terminal cancer, the latter having died after Knife was published. Rushdie is at his best when contemplating his prolonged recovery, the prospect of death, and the fate of those friends.

Those wanting more about the public ’Rushdie’ will not be disappointed. A long section is devoted to A, the assassin, the assailant, the asinine man he doesn’t name. Rushdie imagines several ‘conversations’ with A about his religion and motives. Rushdie even ventures to the Chautauqua County Jail where A is held, still awaiting trial due to his not guilty plea. They have never met.

Chautauqua County Jail where A is held, still awaiting trial.

Rushdie’s deep knowledge of literature and more than a few movies prompts many asides, as well as allows him to cite previous knife attacks on writers. One was Samuel Beckett, stabbed by a pimp in Paris in 1938 when he was writing his novel Murphy. Beckett went to the pimp’s trial and asked why he had done it.

The answer: “Je ne sais pas, monsieur. Je m’excuse.” (“I don’t know, sir. I’m sorry.”) Rushdie doesn’t have the satisfaction of remorse from his attacker, and doesn’t know if he will attend the trial in person, though he is expected to give evidence.

Another famous knife attack is that on Egyptian Nobel prize winner Naguib Mahfouz in 1994, also due to views on religion, a topic that still riles the Rushdie of old. He decries the “weaponising” of religion: evangelical Christianity for its stand on abortion and women’s rights in the US; radical Hindu nationalists for their sectarianism in India; and, of course, Islam for its terrorist regimes in Afghanistan and Iran; and Saudi Arabia and other countries for their authoritarianism.

More recently, Rushdie has weighed into the new generation of Western protesters who support Hamas in Gaza. A former leftist who was at university in England during the 1968 student revolts around the world, Rushdie now questions the demands from so-called progressives for a “free Palestine”.

Pro-Hamas protesters in London.

“Right now, if there was a Palestinian state, it would be run by Hamas and that would make it a Taliban-like state … It would be a client state of Iran.” Instead, he is more pro-free speech than ever, insisting on the need to “defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty, and stupidity”.

He laments that “freedom is everywhere under attack” thanks to the illiberal notion that “protecting the rights and sensibilities of groups perceived as vulnerable [should] take precedence over freedom of speech”.

Elaborating on his views about Knife with Le Monde, the French newspaper, he observed that the old distinctions of left and right no longer apply. “There’s lots of things which are now on the left which I actually don’t like at all: the rise of political correctness, the kind of imposed orthodoxy, how you must speak, how you must talk, what you can and what you can’t.”

Despite sounding angry, Knife is not a work of self-pity or recrimination. While Rushdie’s admirers will lap it up, others may be put off by its gruesome content. This is understandable. It also put me off at the start. Who wants a description of how much damage can be wielded by 14 stabs in 27 seconds? The eight hours of surgery, medication that often went wrong, therapy on an unresponsive left hand, and six weeks in two hospitals that follow are just as harrowing.

The knife just missed Rushdie’s brain, and he lost sight in his right eye. But Rushdie is back with a litany of wise observations, many of them literary, and you will learn much more than you expect.

Knife: Meditations after an attempted murder, by Salman Rushdie (Jonathan Cape).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.