The post-capitalist world of modern business

Sir John Kay says nearly everything you are told is wrong.

The Corporation in the 21st Century: Why (almost) everything we are told about business is wrong, by John Kay.

Sir John Kay says nearly everything you are told is wrong.

The Corporation in the 21st Century: Why (almost) everything we are told about business is wrong, by John Kay.

The sorry saga of the National Government’s school lunch scheme provides a lesson in business practice that would challenge even the most sanguine guru.

The history of business is one of ingenuity and innovation. Without it, the modern world wouldn’t exist. Yet commercial activity is often reviled for its inherent lack of morality, even though its purest form rests on an underlying trust between individuals or organisations.

One of history’s greatest achievements was industrialisation based on mass manufacture. It exponentially lifted living standards in the early part of the 20th century.

Henry Ford first applied an assembly line to the production of the Model T in 1909. Ten thousand were produced in that first year. Six years later, 250,000 were made, and the price had dropped more than 50%.

At the end of World War I, the price has fallen further and one million were sold, fulfilling Ford’s goal of turning a bespoke item for the elite to a product that an assembly worker’s wage could afford.

This was also the aim of the Government in turning an unfunded free meal scheme bequeathed by its predecessor into the latest welfare state entitlement.

Instead of installing kitchens and professional chefs in all eligible schools, or retaining the services of artisan businesses, the contract providers could use economies of scale and mass production.

Business guru Sir John Kay.

In practise, however, this had more than a few teething problems in delivery and quality. It fuelled the Government’s perennial critics, as well as those who despise commercial practice. To them, the extra costs of retaining the old system were not a priority despite the Government running a huge deficit.

A business guru analysing such a problem might judge the scheme unsustainable and urge its abolition. Pupils (or more accurately their parents) would be expected, as before, to provide their own lunches at their own expense.

The history of corporations is full of such stories. Ideas are tried out; some fail, others succeed.

Few have explained this process as well as Sir John Kay, a bank economist turned academic and author of many bestselling titles. Three of them are The Foundations of Corporate Success (1993), The Truth About Markets (2003), and Other People’s Money (2015). Three of his books are collections of his Financial Times columns.

His latest, The Corporation in the 21st Century, has rightly been judged one of the best business books of 2024. It is plainly written and aimed at a wide audience – from those interested in business as a career to those who are curious but largely ignorant, much like those who piled into the school lunch controversy.

The book’s scale is broad in the historical sense and ‘old school’ in the best way. Kay’s background is a Scottish education that graduated into lecturing at Oxford University and the London School of Business, while also being a consultant on banking, taxation, and other issues to the British and Scottish governments.

His appeal is based on his ability to explain business in terms that avoid what he considers the long-vanished clichés of capitalism, socialism, and economics that obscure the realities of modern business.

Some of these will be a surprise, as Kay detests the cynicism in business that spawned virtue signalling, including the dubious worth of DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) and ESG (environmental, social, and governance) concepts, shareholder value, and efficient market theory.

Instead, he writes about business as a collaborative activity that pursues the provision of goods and services in the most efficient way possible. This activity is a community good that, through productive effort, rewards all involved with social and personal fulfilment.

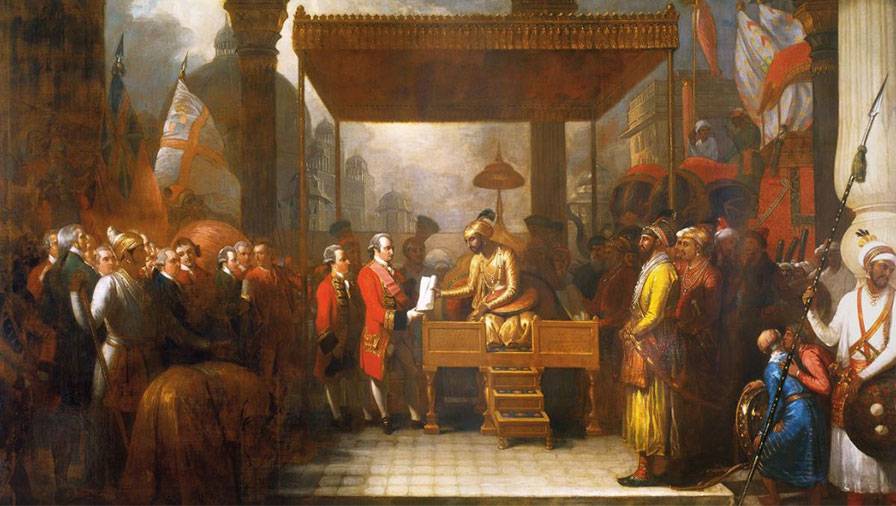

The book takes us through the origins of the corporation in the privately owned enterprises such as the East India Company and the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) that foreshadowed the British and Dutch empires.

Benjamin West’s recreation of the Treaty of Allahabad in 1795, giving the East India Company taxation rights.

The biggest changes that occurred the 19th century’s transformation were led by the growth of railways, the incorporation of institutions, the creation of public capital markets, and the availability of mechanical power. New industries arose, such as those centred on automobiles and electricity.

A century later, manufacturing went into decline in North America and northern Europe, while service-based industries thrived. Some of the oldest – hospitals and universities – outlasted factories. The oldest corporation in the Western hemisphere is Harvard, founded in 1650.

Kay takes a benign view of economic growth. In developed countries – which he labels the Global North but includes parts of Asia, Australia, and New Zealand – growth is largely about better and more complex rather than bigger and more.

In a challenge to the GDP measure, Kay gives a wider definition of growth: Facebook, Google, and Siri; email; instant access to a million songs. It is also means low-cost air travel, services such as Uber, and the availability of counselling and gene editing.

Then there’s varifocal glasses, Bluetooth-connected earphones, GPS navigation, and mobile banking. The list goes on, of ideas and inventions that make life easier. “Modern economic growth is about building collective intelligence into familiar resources to create new products and still more advanced capabilities,” Kay writes.

Uber makes travel cheaper and more convenient, Kay says.

This should alert the reader to think more about politicians’ claims of growth. The benefits of the examples above are poorly measured in national output figures. If these incremental and occasionally game-changing business innovations were better appreciated, public understanding would be enhanced. It might throw doubt on whether recessions have any meaning.

An example, developed by Nobel Prize-winning economist William Nordhaus, is the price of light measured by human effort over millions of years. Fire was once the only source, followed by tallow candles and then the electric light bulb. He calculated the cost of providing light had diminished greatly. Today’s LED lighting has lowered that cost even more dramatically.

The caricature of the cigar-smoking capitalist no longer exists.

The idea that growth means fewer and scarcer resources is one of Kay’s bugbears. “We haven’t run out of arable land and progress will not be halted by a shortage of lithium. All physical resources have finite limits but human ingenuity does not.”

While Kay takes issue with economists over such matters, he is even more scathing about financiers and investors, who ignore the basics of what makes a successful company. Typically, it is run by people who take little notice of economics but are adapting every day to meet the needs of their customers. Business decisions are more likely to be based on the demands of the market and social expectations than to the legal status of shareholders.

The loss of owner control is a central theme in Kay’s definition of the modern corporation after it passes the foundation stage. The classic caricature of the cigar-smoking capitalist no longer exists.

Today’s major players are influencers such as George Soros or the Koch brothers, media barons such as the Murdochs and Jeff Bezos, and major asset fund managers. Wealth is so widely spread, including through sovereign funds, that taxing it make little sense. “Twenty-first century business needs little capital, mostly doesn’t own the capital it uses, and is not controlled by the people who provide that capital,” Kay states.

Capital is employed on the same basis as labour is contracted and utilities are paid to suppliers. In essence, a business is defined by its capabilities, rather than by what it produces. Irish aircraft leasing company Aercap ‘owns’ US$70 billion ($120b) of aircraft that are operated by dozens of airlines. Yet Aercap has no capital of its own and is funded by debt.

No book on modern business, even one with Kay’s grasp of communication skills, can avoid heavy dollops of jargon and buzzwords. Kay’s collection includes some that are obvious – collective knowledge and intelligence – while others require deeper explanation.

One is “disciplined pluralism”, which is an evolutionary process akin to Charles Darwin’s natural selection. Disciplined pluralism is the basis of a market economy and is superior to a state-directed one that lacks both discipline and pluralism.

LED lighting has dramatically reduced costs.

It works because it allows the freedom to experiment but is quick to end unsuccessful ones. “The proper goal of corporate activity is the flourishing of the multiple stakeholders … employees, investors, suppliers and customers, the communities in which it operates, and the corporation itself … [It] must contribute to the flourishing of the society in which it operates.”

If you think this is too rose-tinted, be assured Kay presents an analysis of why many businesses fail, including criminality and the destructive nature of takeover and mergers (“managers would do better to focus on building, rather than acquiring, a great business”). These provide the most compelling content, as local examples come to mind.

As he notes in debunking the efficient market thesis: “Any idea that the market knows more about the corporation’s future than its management knows – or could or should know – represents the triumph of abstract theory over common sense.”

Aercap leases aircraft to these airlines.

The Corporation in the 21st Century: Why (almost) everything we are told about business is wrong, by John Kay (Yale University Press (US) and Profile Books (UK)).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.