The paradoxical dawn of the modern age

How the 17th century laid the foundations of today’s world.

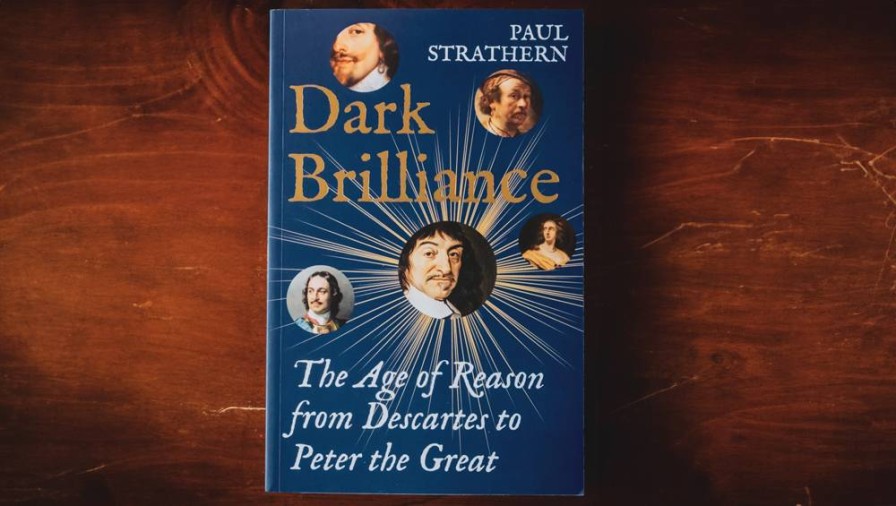

Dark Brilliance: The Age of Reason from Descartes to Peter the Great, by Paul Strathern.

How the 17th century laid the foundations of today’s world.

Dark Brilliance: The Age of Reason from Descartes to Peter the Great, by Paul Strathern.

Empires have long been the driving force of history through the expansion of civilisations that imposed values, peace and stability.

Those who challenge the imperial version of history must ignore the progressive roles of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, not to mention those of the Americas, China, India, and Africa.

In The Great Imperial Hangover, Singaporean historian Sami Puri provided a non-Eurocentric version, reaching a conclusion that contradicted those who said the modern European empires were more insidious than others merely because they were successful.

Paul Strathern.

Their legacy came from the advantages they generated in trade, law, language, and culture. To extend the metaphor in the introduction: “Commerce was the fuel of empire building but war was the engine that drove the process,” Puri states.

No century demonstrated this as much as the 17th century, in which the imperial powers of Europe began to extend their reach to all parts of globe, conquering everything in their path. Often described as the Age of Reason, it was a period in which human intellectual achievement made some of its greatest advances.

But British historian Paul Strathern claims it was undermined by a “far murkier world of instinctive impulse and dark irrational drives”. While the Dutch and British merchants were going global with commerce, and religious pilgrims from Europe began to settle the Americas, purges against women in ‘witch trials’ were also common.

Ideas of freedom and the nation state began to percolate at the same time as colonisation and the age-old practice of slavery spread from Africa across the Atlantic.

In Dark Brilliance, an intellectual history from Descartes to Russia’s Peter the Great, Strathern puts the case for paradoxical progress. One was the hope for a better society based on egalitarianism and socialism. “Eventually the dream soured and the command economy degenerated into the command economy,” he observes.

Strathern is a traditionalist, who can look back in his 80s on a career of writing mainly about the Italian Renaissance, Napoleon, and the origins of medicine and science. Earlier, he produced a handful of novels based on his travels in Asia and Africa. On top of this are dozens of 90-minute profiles of major philosophers, writers, and scientists.

This has enabled him – within 340 pages, not counting extensive sources notes, colour illustrations, and an index – to produce a highly readable account of everyone who was anybody as the Little Ice Age thawed.

Northern Europe in the 16th century was noted for its major storms, long winters, no summers, famine, and low harvests. In the first half of the 17th century, the 30 Years War between the Catholics and the Protestants ended with a world order based on nation states, treaties, and the conduct of diplomacy.

René Descartes set the intellectual pace for the 17th century.

René Descartes led a wave of intellectual activity that separated the mind and body based on mathematical principles, drawing the ire of Rome. The young Queen Christina of Sweden gave him refuge in Stockholm and most of the philosophers who followed championed reason over faith.

The most influential of the English philosophers, Thomas Hobbes, travelled throughout Europe, which was in a ferment of political extremism: the overthrow of the monarchy in the English Civil War, religious upheaval in Calvinist Geneva, the Inquisition in Spain, and Savonarola’s Florence.

In Leviathan, Hobbes theorised on how the natural anarchy of human society could best be organised. Strathern says: “The power of Leviathan [the state] was dependent upon its ability to protect those over whom it was sovereign.”

Early scientific breakthroughs occurred in the Protestant Dutch republic, which attracted enterprising Huguenots, Jews, and other persecuted minorities. Christiaan Huygens developed early theories of gravity, the telescope, pendulum clock, and the concept of light.

Christiaan Huygens. Portrait by Caspar Netscher (1671).

Source: Museum Boerhaave, Leiden.

Portugal and Spain led the ‘Age of Discovery’ with its explorers going eastward and westward to find other worlds rich in food and mineral wealth. Ferdinand Magellan had circled the globe in 1522 but it wasn’t until the monopoly companies set up in England and Holland that these exotic products could be traded in scale.

Financial bubbles in tulips and the like were the downside of commercial speculation. Wars were fought between the English and the Dutch in North America and South Africa. The English East India Company became the world’s largest enterprise, trading in opium, spices, tea, coffee, and cotton.

Strathern revives the pioneers of modern business tools, such as stock exchanges, futures, adding machines, and book-keeping. Mathematician and physician Sir William Petty, for instance, rose from being an official during Cromwell’s Protectorate to be the founder of modern economics a century before Adam Smith. John Graunt was the father of statistics.

Medical and scientific advances were possible through the development of lenses, syringes, and microscopes led by, among many others, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Francis Bacon and Robert Hooke pioneered the scientific method of experimentation; Robert Boyle was the world’s first modern chemist; and William Harvey demonstrated how blood flowed around the body.

Isaac Newton was the greatest mind in England. Source: Anonymous portrait.

Their quest for knowledge was matched by polymaths such as Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton, who both combined interests in theology with new ideas in mathematics (they invented rival forms of calculus). Newton was considered the greatest English mind in the 17th century; France had Blaise Pascal and Michel de Montaigne.

The philosopher John Locke developed his ideas on empiricism during a time of great political turbulence in England, having to flee to Holland after the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II.

There, Locke met another great philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, and later returned to England with William and Mary of Orange in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 that established a constitutional monarchy. (One that has “supreme power in theory, yet remains all but powerless in practice,” according to Strathern.)

Strathern plays down the role of monarchs, apart from France’s “Sun King, Louis XIV, who ruled France for 72 years from his opulent palace of Versailles, and Russia’s Peter the Great, who toured Europe to pick up ideas and manpower for his modernisation programme”.

Under Louis XIV, French culture blossomed with painters such as Nicolas Poussin, dramatists Jean Racine and Moliere; its world-leading cuisine; and, of course, the invention of champagne.

Profiles of the great artists take up more space than you might expect: El Greco and Velazquez from Spain; Caravaggio and Artemisa Gentileschi from Italy; Rubens, Rembrandt, and Vermeer from Holland.

Samual Pepys witnessed the Great Fire of London. Source: Royal Museums, Greenwich

In literature, Don Quixote by Cervantes, the poet John Dryden, Samuel Pepys’s Diary (1660-69), and John Milton’s Paradise Lost are given due attention, while composers Henry Purcell and Caludio Monteverdi are not overlooked.

This focus on culture is the main attraction of Dark Brilliance. The legacy of the 17th century endures today, as much in the architecture of Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London in 1666 as the paintings and literature.

Strathern writes for the general reader, and his work is often described as ‘once over lightly’. It also lacks insights based on modern knowledge and interpretations. Instead, it provides gossipy items to justify the ‘dark underside’ of the title. This is for readers who want an accessible update on their historical knowledge, without plodding through dense scholarly works.

Dark Brilliance: The Age of Reason from Descartes to Peter the Great, by Paul Strathern (Atlantic Books).

Next week: For more on the 17th century: a review of Greene Lyon, a novel based on the life of Isaac Newton by Alan Goodwin, a District Court Judge in Manukau, Auckland.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.