The one-click way to winning and losing

OPINION: Why Amazon.com succeeds and others don’t.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

OPINION: Why Amazon.com succeeds and others don’t.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

New Zealand’s gentle slide down the rankings of the world’s richest countries should be no surprise.

Global Finance compares countries by considering inflation rates and the cost of local goods and services. The resulting figure is called purchasing power parity (PPP), which is often expressed in international dollars (what US$1 buys in the US) to allow comparisons.

In 2015, New Zealand ranked 30th, with a per capita wealth (GDP based on PPP) of US$36,342.72. Seven years later, in 2022, New Zealand eased to 32nd but wealth rose to US$50.411.

Luxembourg rose to the top in 2022, after breaking through the US$100,000 mark in 2014. Not far behind were Singapore and Ireland, the latter showing the most spectacular jump through the ranks from 14th. Irish per capita wealth rose from US$48,786.91 to US$124,596, a near threefold increase.

How? Global Finance: “Ireland was one of the hardest hit by the 2008 financial crisis. Following some politically difficult reform measures like deep cuts to public-sector wages and restructuring its banking industry, the island nation regained its fiscal health, boosted its employment rates, and saw its per capita GDP almost double in a short amount of time.”

That sounds like New Zealand’s reforms in the late 1980s. It’s a scenario that will be needed again if New Zealand is to reverse its decline. The insidious factor is inflation, which rocketed to levels not seen last century. Unfortunately, the cure remains the same: a tough dose of monetary policy and, dare I say it, austerity politics.

That can only be achieved by a change in government at the end of this year. Whether voters agree remains to be seen.

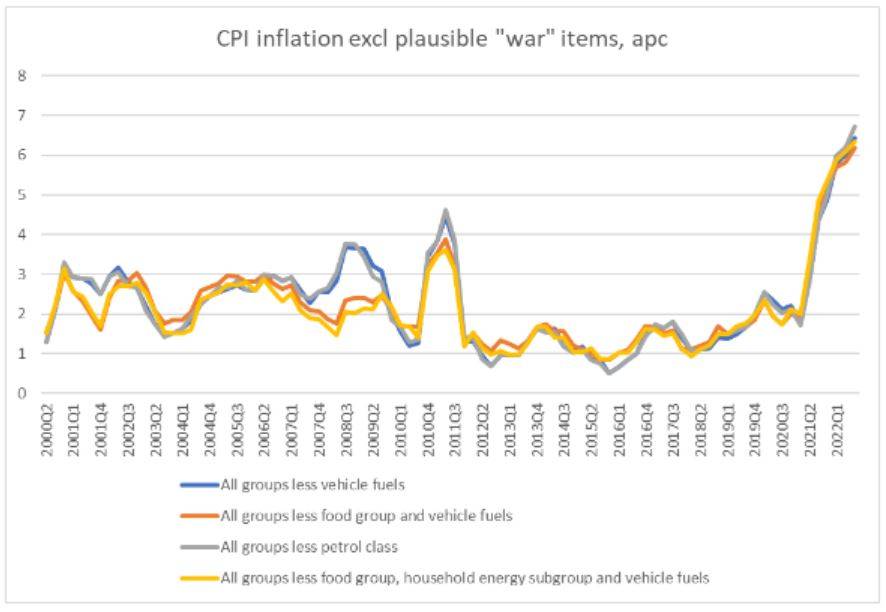

Inflation measures since 2000. Source: Michael Reddell.

The inflation graph, provided by Michael Reddell, shows the three-term Labour-led governments up to 2008, when the global financial crisis hit, held inflation at a steady1.5-3.5%.

The change of government, and reaction to the GFC, brought greater volatility as austerity measures in the first term brought inflation to below 2%. That lasted through the next two terms of National-led governments and the first term of the Labour-New Zealand First coalition.

The inflation genie was suppressed until 2021 until a combination of cost-pressures, loose monetary policy, labour supply restrictions, and other inflation-friendly policies did their worst.

It’s a well-researched area that governments in election years favour bad but popular policies over good ones. The price is paid when they lose, and the incoming government is forced into austerity measures.

Inside an Amazon facility.

That means taming inflation by the only economic means possible: cutting costs, looking for efficiencies, and delivering services as cheaply as possible. It is the same formula that drives one of the world’s richest companies, Amazon, with its legendary customer focus and economies of scale.

It’s been said, accurately, that data-rich Amazon knows its billions of customers better than any government and is more effective at communicating with them. Its market capitalisation of US$1 trillion (half of what it was during the pandemic) makes it the fifth most valuable company in the world. Revenue last year topped half a trillion dollars.

It’s already trimming its staff to meet global market conditions. In January, it announced job cuts of 18,000 and another 9000 last week. The latest moves affect Amazon Web Services, advertising, the company’s Twitch game platform and PXT – the ‘People, Experience and Technology Solutions’ group. These cuts must be viewed against a global total of 1.2 million staff. In the US, it’s the second-largest private sector employer after Walmart stores.

Amazon also put on hold the second phase of its multi-billion-dollar second headquarters development at Arlington, near Washington DC, and closed its futuristic Amazon Go convenience stores in San Francisco.

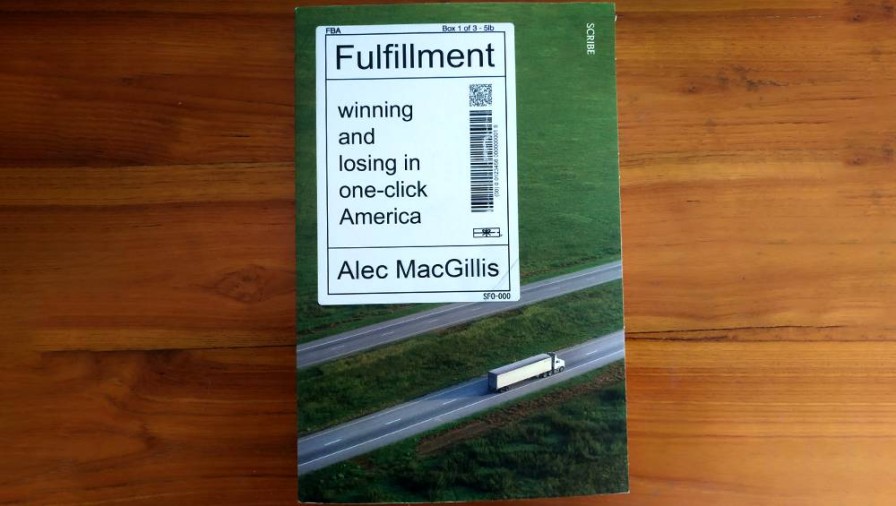

Amazon is a closely studied company for its culture and commercial nous. Some is favourable but much is not. A recent example is Fulfillment, by Alec MacGillis, a reporter for ProPublica, an investigative website.

Alec MacGillis is an investigative reporter for ProPublica.

MacGillis was formerly with The New Republic, The Washington Post (now owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos), and the Baltimore Sun. ProPublica specialises in obtaining and releasing confidential tax data about wealthy people, most notably Bezos and, of course, Elon Musk.

Although Fulfillment (the American spelling was not changed for the Australian-produced edition) is ostensibly about Amazon, it reads more of an economic history of the US with a focus on the downside, as if one company was responsible for all that country’s ills.

The narrative weaves stories about several individuals, most of whom have been negatively touched by some facet of the company’s operations or changes to their communities. They include a forklift driver and a salvaged-brick seller from MacGillis’s hometown of Baltimore; a lawyer-turned-artist and a gospel-choir leader from Seattle; and a young politician and a truck driver from Ohio.

In my judgement, all made poor personal decisions, though this does not fit MacGillis’s depiction of a ‘winner takes all’ society. This also applies to cities, because Amazon’s incredible growth has mainly benefitted the “hyper-prosperity” of Seattle, Northern Virginia, and Washington DC rather than the “left behind” companies and places: Bethlehem Steel in Baltimore, National Cash Register in Dayton, and Bon-Ton in Pennsylvania.

The latter appeal to Amazon only if deserted industrial plants can be converted into “fulfilment” (distribution) centres, while tax breaks decide the location of the higher-paid, skilled positions in Amazon’s tiered universe.

"The company had, in a sense, segmented its workforce into classes and spread them across the map: there were its engineering and software-developer towns, there were the datacentre towns, and there were the warehouse towns," MacGillis observes.

Amazon fulfilment centre in Columbus, Ohio.

This is a bit far-fetched, as it reflects the differing needs of the businesses and the places that best meet them. In Ohio, this meant favouring growth-conscious Columbus over its tax-hungry neighbours. Or Musk moving his multi-faceted businesses to low-tax Texas from red-tape loving California.

Nevertheless, Amazon’s path has featured deaths and injuries in its workplaces, third-party providers feeling screwed when their goods are copied by Amazon’s own knockoffs, and public officials who signed off sweetheart deals but got little in return in the form of tax revenue.

Hyper-prosperity, for MacGillis, means high housing costs as well as its obverse: homelessness. Seattle – also home to Microsoft and Starbucks – moved from a sleepy hollow with only one major employer, the Boeing aircraft company, to rival San Francisco and Silicon Valley with its wealth disparities.

At the conclusion of Fulfillment, MacGillis describes this paradox of American’s new version capitalism: “The spread of blight and abandonment in one city, the spread of congestion and exclusion in another only an hour away.”

He suggests a solution that involves redistributive politics: “… [B]reak up the giants that had concentrated wealth not only in themselves, but in the places in which they had chosen to reside…

“… disperse prosperity … to restore some balance, to deter resentment and despair one set of places and complacency and anxiety in the other.”

It’s a vision that clashes with the realities of doing business, particularly those critics who see Amazon as a monopoly rather than a cost-cutter delivering the lowest price to the buyer.

The Lord of the Rings: Amazon Studios did not make the second series in New Zealand.

MacGillis gives some credit where it is due when he quotes Teresa Carlson, head of AWS, the world’s largest supplier of cloud services: “Thanks to our economies of scale, AWS has reduced our prices 66 times since we launched in 2006, under no pressure. When we get economies of scale, we give them back to our customers and our partners.”

That’s good news in the llght of Mercury signing a deal to supply an AWS data centre from a wind farm in Manawatū. So is Musk’s Starlink offer of cheaper satellite broadband for all New Zealanders.

But it raises the question of why the government failed to persuade Amazon Studios to make the second season of the world’s most expensive TV series, The Lord of the Rings, in a country once synonymous with Middle-earth.

Fulfillment: Winning and losing in one-click America, by Alec MacGillis (Scribe).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.