The watchers and the watched

ANALYSIS: New Zealand’s search for seditionaries, subversives, and spies.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

ANALYSIS: New Zealand’s search for seditionaries, subversives, and spies.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

A modern state cannot function without an apparatus that contains some form of surveillance over its citizens. It must constantly be prepared to search for actual or potential seditionaries, subversives, and spies.

Every country, to a greater or lesser extent, keeps an eye on its subjects or outsiders who attempt to undermine or overthrow both itself and the interests and values it promotes and protects.

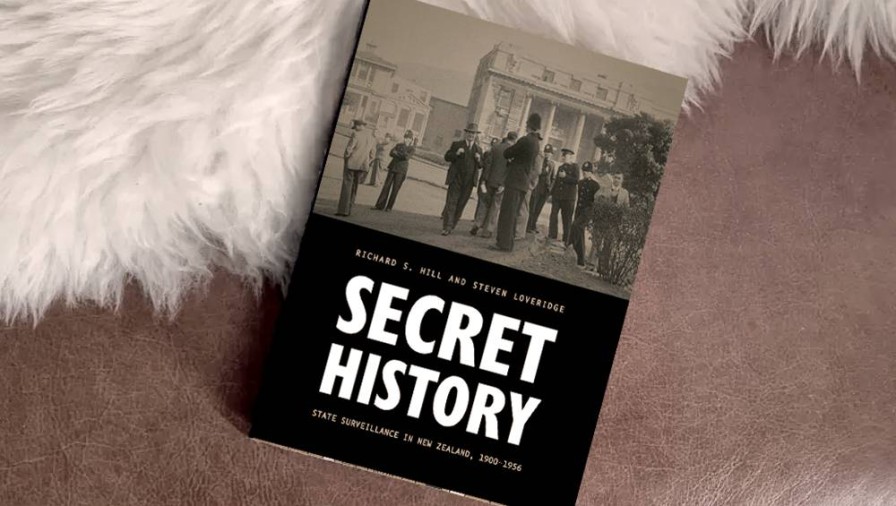

This is the starting point for Secret History: The History of Security Intelligence in 20th century New Zealand, Volume 1, an impressive (and expensive at $80) work by two experienced professional historians, Emeritus Professor Richard S Hill and Steven Loveridge. The first book covers the 20th century up to 1956, with the second volume, due out next year, taking the account through to the present day.

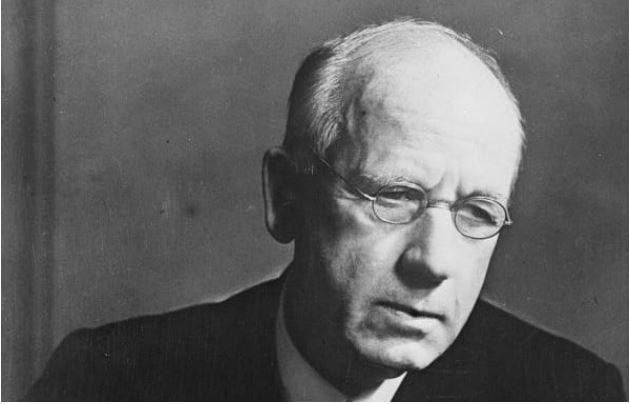

Emeritus Professor Richard S Hill.

Secret History has the look and feel of an ‘official’ history, in that it has privileged access to government archives including those of the New Zealand Police. This is always a contentious area, as no writer or historian wants to be bound by conditional access.

When the topic is policing and matters of national security, sensitivity is even greater on the part of those holding the files. For example, I know that Graeme Hunt, formerly a senior journalist at The National Business Review, gained generous access to previously secret files for his pioneering history, Spies and Revolutionaries (2007), and Black Prince (2004), his biography of trade union leader FP Walsh. But many were still withheld, particularly where events were recent, such as the Rainbow Warrior sinking and the Israeli passports scandal.

Cybèle Locke reports she was refused permission to see the full personal files on communist and trade union leader Bill Andersen for her recent biography, Comrade (2022).

Hill and Loveridge are both respected researchers and appear to have had little trouble on access, given the published volume stops at the same year the New Zealand Security Service, later NZ Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS), was formally established as an independent entity.

In Australia, a commissioned ‘official history’ of the Australian Signals Directorate by Professor John Blaxland was disrupted when the agency’s head changed. The new appointee pulled the plug on the book covering events over the past 25 years as well as taking issue with the extent of historical context going back to ancient times of Greece and Rome, and Australia’s early colonial period.

A new ‘official historian’ was appointed, while Blaxland’s project was revamped with input from Clare Birgin, and finally appeared in April under a new publisher. Blaxland had previously written the ‘official’ history of ASIO, Australia’s equivalent of the NZSIS, under an arrangement that gave the agency veto over security issues.

Steven Loveridge.

Hill and Loveridge have had no such problem. Hill has written several histories of policing in New Zealand as well as Crown-Māori relations. Loveridge contributed to last year’s New Zealand’s Foreign Service, commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and a chapter on the ‘rightward fringe, 1950-70’ in Histories of Hate (2023).

Apart from embarrassment to successive governments and agencies, putting material collected in surveillance operations into the public arena must be sensitive to its veracity and the impact on those who were monitored.

In interviews with families who had members with personal files, Hill and Loveridge report that even the redacted versions did not bring closure. “Seeing such routine documentation, sometimes in extraordinarily intimate detail, of the lives of loved ones has evinced a mix of reactions: astonishment, anger, and a sense of violation and betrayal…”

No doubt the same was felt when the Stasi files were opened after the collapse of the German Democratic Republic, which by most accounts had the world’s most intensive network of informants, often involving members of the same family.

Of course, nothing like that happened here, unless you happened to be a communist, socialist, radical student or unionist, an alien immigrant, or wanted to work in the public service. The labour movement was an early target for the New Zealand Police Force because of widespread class warfare and civil disobedience in 1912-13.

“Policemen infiltrated all strata of dissident activity … in mines, factories and wharves, and secured informants within many political movements and organisations.” In the lead-up to World War I, compulsory military training was introduced and so pacifists, and later Jehovah’s Witnesses, were added to the list.

Hill and Loveridge break the period under review into seven chapters, treating each with the same methodology: an overview of the social, political, and economic context; details of the agencies employed (ranging from the Police Force to Post & Telegraph censorship); an account of the operations carried out; and, finally, an assessment and a conclusion.

This is an exhaustive exercise for a book of 400 pages (including index, primary and secondary sources, and footnotes). It functions as a parallel history of New Zealand from the perspective of a maintaining and orderly peaceful society that is protected from internal and external dangers.

Readers will be entertained by the inevitable rabbit holes, false flags, fantasists, and conspiracies that abound in these secret worlds. Police drilled holes in the walls of Dunedin’s Good Templars Hall to eavesdrop on the short-lived Militant Workers League. An English dancer, known as the ‘girl in red’, was suspected as a spy in 1935 because she cycled around the country for her shows.

Police card index files on Auckland trade unionists.

On the serious side, active monitoring of the labour movement was constant throughout, heightened during the two world wars by fears of foreign agents, imported propaganda, and the impact of events such as the Irish civil war, the Bolshevik revolution, the Depression, and the rise of fascism in Spain, Germany, and Italy.

The election of a Labour government in 1935 changed the emphasis if not the purpose of surveillance activity. The Police Special Branch had substantial files on several cabinet ministers from their earlier activity in the labour movement. Peter Fraser, appointed police minister and later prime minister, was jailed for sedition in World War I.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser pursued 'a relentless quest to suppress opposition'.

As PM, Fraser pursued a “a relentless quest to suppress opposition to his war time policies”. The Communist Party (CPNZ), which in 1938 had fewer than 100 members, was forced underground (but not banned) after the Stalin-Hitler Pact in 1939. A ban on the People’s Voice was lifted in 1943 after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.

The CPNZ’s membership peaked at 2000 in 1945, boosted by goodwill for the Russian war effort, but was soon in decline again with revelations in the early 1950s about the extent of Soviet penetration of Western governments.

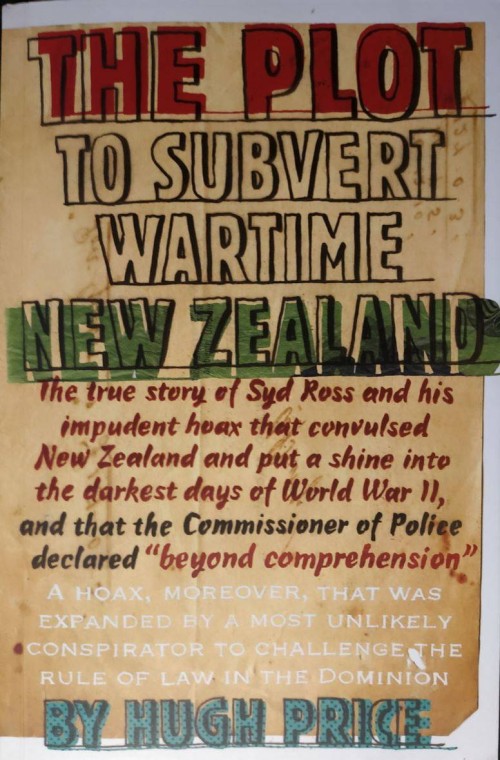

Police control over intelligence gathering was challenged several times, as the military asserted their interest in national security and international links. The establishment of the Security Intelligence Bureau in 1941 ended less than two years later amid scandal when its head, Englishman Major Kenneth Folkes, hired ex-convict and conman Sydney Ross.

Hugh Price's book on the fraud that sank the Security Intelligence Bureau in 1943.

Police played a major role in exposing the Ross hoax, leading to Folkes being sent home. “Apart from institutional patch protection, at stake was the struggle between two models of security intelligence: the ethos of police-based surveillance versus a military-style operation falling outside the criminal justice system.”

Pressure to restore an independent agency that aligned with those of Allied countries continued, as New Zealand was considered the weakest link in what later became known as the Five Eyes network. The Soviet legation in Wellington was staffed by 15 married couples in 1956, while New Zealand had ended its diplomatic representation in Moscow in 1950 (it was later restored by a Labour Government in 1973). The exposure of prominent New Zealanders as suspected Soviet agents in the 1950s – confirmed in later years – added to the momentum.

While subsequent events are the subject of the next volume, the authors note the considerable intelligence gathered on some individuals in the early stages of the Cold War did not prevent them from distinguished careers in the public service, politics, academia, and the arts.

The dilemma for open and liberal societies is choosing a balance between the extent of surveillance and the rights of individuals to hold hostile opinions. On the evidence so far, the authors say, in answer to Juvenal’s question: Who watches the watchers? – “essentially, no one”.

Secret History: State surveillance in New Zealand, 1900-56, by Richard S Hill and Steven Loveridge (Auckland University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.