The grim reality of a green future

ANALYSIS: Climate protection means no cars, no planes, and wartime rationing.

The End of Capitalism: Why growth and climate protection are incompatible – and how we will live in the future, by Ulrike Herrma

ANALYSIS: Climate protection means no cars, no planes, and wartime rationing.

The End of Capitalism: Why growth and climate protection are incompatible – and how we will live in the future, by Ulrike Herrma

Political theories may be subservient to the realities of practice in most democracies. But recent events in the United States show the power of ideology if backed by polling and votes.

Polls in New Zealand, and among Western countries in general, confirm the resilience of ideas opposed to capitalism. Its strongest supporters are younger generations and women of all ages.

Green politics began as an anti-capitalism movement, replacing socialism associated with trade unions and the industrialised working class. Its major appeal was to an educated middle class that associated capitalism with economic growth, pollution, and environmental damage. Inequality and social justice were later added to the mix.

While this gives the New Zealand Greens a loyal 10% of the total electorate, it is climate politics that has provided a larger basis for the so-called progressive movement’s opposition to capitalism.

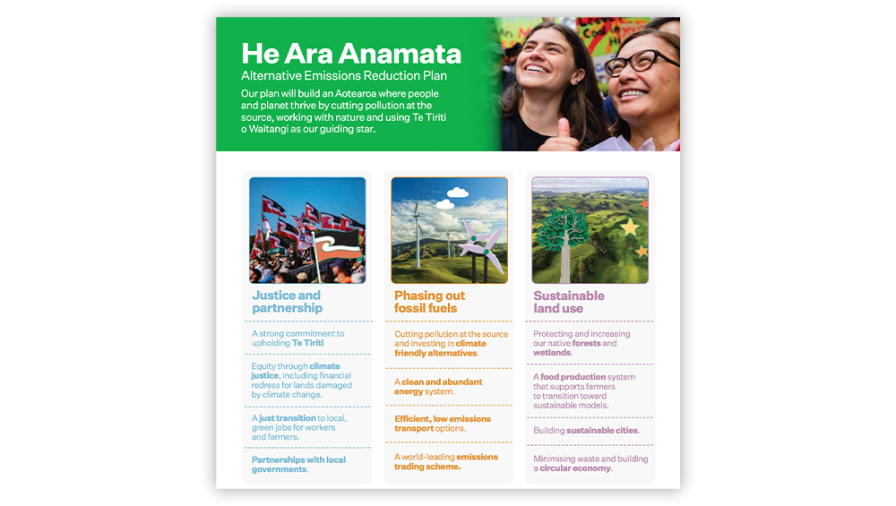

A recent Greens carbon emission reduction policy document, He Ara Anamata, is a forceful statement of anti-capitalism that adds a historical dimension of “violent land and resource theft of iwi Māori” to this statement:

“Capitalism – this current insatiable, unsustainable economic system – requires colonisation and the constant assimilation of new frontiers to exploit and extract from," it says.

After that statement comes the goal of an “economy based on climate justice [with] policies that are underpinned by Te Tiriti [and supported by] circular systems, renewable energies, and just transitions for workers …”

I am indebted to Chris Trotter for this quote as he explains ‘circular systems’ as “autarky” – an economic concept of self-reliance associated with authoritarian regimes. He also notes the “enormous difference between ‘just transitions’ arranged for workers, and the securing of economic and social justice by workers” [Trotter’s italics].

In other words, He Ara Anamata is hinting at junking democracy in favour of methods employed by history’s fascist and communist regimes.

An alternative that doesn’t steep to ethno-nationalism comes from Germany’s foremost Green economist and communicator Ulrike Herrmann. The End of Capitalism is her fifth book and the first to be translated into English.

Ulrike Herrmann.

Three of them, which are widely quoted in the new book, are Der Sieg des Kapitals (The Triumph of Capital, 2015), Kein Kapitalismus ist auch keine Losung (No, Capitalism is not the Solution, 2018) and Deutschland, ein Wirtschaftsmarchen (Germany, an Economic Fairy Tale, 2022).

They show a deep knowledge and admiration for capitalism as a system; so much so, Herrmann could be mistaken for the likes of Joseph Schumpeter and other free-market economists. Her history of capitalism places it firmly as the generator of industrialisation that occurred in Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Post-plague, England and Scotland had a labour shortage, which created a need for factory machines that did not occur elsewhere in Europe. Pastoral farming meant peasants were no longer tied to the land, their factory wages fuelled demand for consumer goods, and coal provided the cheapest form of energy. The invention of steam-powered railways topped off a revolution that made capitalist Britain the richest and most powerful country in the world.

Hermann provides this context: “Capitalism was neither planned nor predicted. It developed out of the desire of some textile manufacturers and mine owners to become more efficient and more competitive.”

This “unintended development” was solely due to labour being expensive. “However, its consequences were enormous, as they included the widespread exploitation of fossil-fuel deposits.” This symbiotic relationship lifted the world out of subsistence living and created the society as we know it today.

Hermann goes on to track capitalism’s global growth, in the process knocking down many of the myths attributed by its critics. One of them is that capitalism demands war and exploitation, such as slavery. The latter was well established in many cultures well before capitalism; in fact, capitalism helped end it. Māori get a mention as practising slavery in pre-colonial times.

Exploitation did not create industrialisation or mass consumerism. The European colonies produced mainly luxury goods, such as sugar, coffee, cocoa, tea, spices, and silk. Capitalism had made the colonies possible, not the other way around.

Capitalism had made the colonies possible, not the other way around.

Nor is capitalism a zero-sum game, as Marx thought. Adam Smith observed in 1776 that countries only became rich from exporting if there were other rich nations to buy the goods.

“The richer each individual is, the richer everyone gets,” Hermann concurs, no doubt to the chagrin of her anti-capitalist readers.

Indian spice markets thrived under colonialism. Photo: Marc Shandro

In a world divided into the prosperous North (including New Zealand) and the developing South, Hermann says the latter’s lack of industrialisation was due to labour being cheaper than capital. Some countries – Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China – closed the gap through state-provided capital and protectionism after 1945.

She notes this didn't happen in Africa mainly due to the post-colonial élites sending what capital they had to tax havens rather than investing it. If you think Hermann is getting too enamoured with capitalism, then get ready for her attack on 'green growth' proposals to achieve carbon neutrality.

Her three-pronged assault demolishes carbon capture and storage (consumes too much energy); nuclear power (too costly, wastage problems); and solar and wind (not reliable, useless in Germany’s dunkelflaute – long mid-winter periods with no sun or wind).

She describes the shortcomings in battery technology, the costs of pumping water for hydro power (as suggested at Lake Onslow), and ‘green hydrogen’, which requires electrolysis that is 10 times more expensive than natural gas.

Solar panels need metals.

Another negative for ‘green growth’ – the manufacture of solar panels and wind turbines – is the increased demand for mineral and metals, including rare earths. A replacement for concrete is also unlikely. Cement requires the extraction of CO2 from lime and there’s not enough wood in the world to replace 4.6 billion tonnes used annually.

Those hoping for a digital transformation to eliminate carbon emissions through ‘qualitative growth’ or ‘capitalism lite’ are also scorned. “There is no miracle technology that can suddenly ‘dematerialise’ capitalism,” she argues.

Juliet Schor advocates a circular economy.

Herrmann warms up for a conclusion, that existing practices threatening the climate must be curtailed rather than held on to in the hope of a viable solution. This is where the grim reality of a green future – carbon neutrality by 2050 – means ‘green shrinkage’.

This economy would have fewer goods produced, no car journeys or aircraft flights, less use of chemicals, smaller dwellings, and no new office blocks or logistics centres. Remember, this formula is being suggested for Germany, where alternative land transport includes a vast network of railways, and single-family dwellings are the exception rather than the rule.

Of course, some forms of ‘green shrinkage’ already exist. Libraries provide books for sharing, labour-saving devices are common, and flea markets sell unwanted or used goods. But the New Zealand Greens’ dream of a circular economy, cited earlier, gets short shrift.

The concept belongs to American economist Juliet Schor, who considers “a truly sustainable system will require ecological restoration and technological innovation”. But, to Herrmann, the lack of dynamism ignores the reality of capitalism: “If it shrinks it melts like an ice cream in the sun.”

The realities of green shrinkage continue to stack up: along with an absence of private car and air travel, financial services would shrivel; no growth means no return for life insurance policies or investments; bank lending would no longer exist; and nor would industries lacking carbon neutrality – chemicals, building, and mining.

Some industries will survive: pharmaceutical and healthcare; postal and communications; energy; and software. Herrmann’s model is wartime Britain in the 1940s, where the civilian population was sustained with rationing of some foods, clothing, and other essentials while the rest of the economy was harnessed to fight a war on limited resources.

Queuing for food in London, 1945.

“Britain’s wartime economy was able to work so well because it did not introduce anything radically new, but rather radicalised aspects that were already inherent in capitalism,” she writes, noting that private property rights and businesses continued. Careful planning ensured no-one starved and social harmony was maintained.

Not everything was rationed. Furniture, clothing, and luxuries such as biscuits and chocolate were available on a points system. Restaurant meals were restricted to two courses and price controlled, which enforced an egalitarianism that was widely appreciated.

Herrmann’s green solution might be ridiculed and considered politically impossible. But she bases it on strong evidence that existing means to reach carbon neutrality won’t work. The abolition of capitalism may be necessary, but threatens economic collapse if done badly.

The message is that, if the Greens insist the climate needs protection and capitalism is incompatible, then some hard choices will follow.

The End of Capitalism: Why growth and climate protection are incompatible – and how we will live in the future, by Ulrike Herrmann. Translated by David Shawscribe. (Scribe).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.