The Gonzo journalist and the elusive dictator

One man’s attempt to speak truth to power.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

One man’s attempt to speak truth to power.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

Journalists usually see both sides to a story. An exception is made for television current affairs reporters and documentary makers. In their world, a story is either right or wrong.

British journalist and author John Sweeney is a master of this genre. At 64, he is now a freelancer, limited to Twitter, podcasts, as well as minor print, radio, and web-based outlets. He operates, Gonzo style, with what he calls a camera phone.

Lately, he has been in Ukraine, dodging Russian rockets while recording his exploits. He’s been there since February, just as he has been at every world conflict and flashpoint for the past 40 years.

In May, he took a break back in Britain, using the time out to knock off another book. His work rate is formidable.

John Sweeney in Ukraine earlier this year.

Since 2010, he has written a biography of Europe’s last dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, of Belarus; an expose of Scientology; an account of an undercover trip to North Korea; and an investigation into the death of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. A book on Ghislaine Maxwell is due in November.

In the same decade, Sweeney wrote four novels, some based on his experiences in war zones and revolutions in 60-odd countries, including Algeria, Bosnia, Burundi, Chechnya, Iraq, and Zimbabwe.

He worked for a dozen years at London’s Sunday broadsheet The Observer, before a similar stint at the BBC, reporting for Panorama and Newsnight. His association with the BBC, which ended in 2019, was marked by several controversial episodes, due to his techniques that often went beyond what is acceptable in mainstream media.

“The way I liked to work on Panorama was to push everything to the limit, so that when the bosses pushed back, adding cold milk as they always did, the viewing public would still get something with a bit of flavour,” he explains.

As a result, Sweeney won many awards and prizes for his work, such as on cot deaths after three women were accused of murdering their babies; conmen such as the ‘fake sheikh’ Mazher Mahmood, crooked businessmen; and, most famously, murderous dictators.

John Sweeney at the border in North Korea, where he posed as an academic.

He posed as an academic from the London School of Economics to visit North Korea. He was accused of putting the accompanying group of student travellers at risk and of compromising the future ability of the LSE to pursue studies in other hostile countries.

That programme had five million viewers in Britain but no impact on North Korea. Sweeney had more success in challenging another authoritarian, Vladimir Putin, the target of his latest book, The Killer in the Kremlin. The title is typical of Sweeney’s style: full of allegations, mostly because they can’t be disproved, and written in a combination of bombast and bravado.

Sentences start like this: “The clock struck 13 when I rocked up …” or “I start chuntering into my camera phone when a tough-looking dude…” and “I chewed the fat with…”

No-one expects calm, academic analysis from a war correspondent, but his language detracts from putting this book alongside more serious Putin studies. Sweeney is familiar with these, and quotes them extensively, as he did for background in North Korea Undercover (2013).

John Sweeney confronts Vladimir Putin at the Sochi doorstepping.

But those authors haven’t ‘doorstepped’ Putin with accusations of being a murderer, as Sweeney did in Sochi, site of the Winter Olympics in 2014. Sweeney flew there without a media pass and Putin’s minders didn’t realise the well-dressed bearded gent at a reception was not a local.

The confrontation was filmed, with Putin having to explain deaths in Ukraine after the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17.

Sweeney has pursued Putin relentlessly since the Second Chechnya War in 2000, totting up the long list of victims of Russia’s extensive network of intelligence agencies and secret police. This war against civilians pioneered the use of ‘vacuum’ bombs, torture, and attacks on ‘white flag’ refugees, and were repeated in Syria and again in Ukraine.

Other examples Sweeney blames on the Kremlin are the ‘black ops’ that set off bombings at Moscow apartments in 1999 and killed hundreds in the Moscow Theatre siege of 2002 and the Beslan school shootings in 2004. All were blamed on Chechnyan terrorists despite evidence most of the casualties came from the actions of authorities.

The bridge near the Kremlin where Boris Nemtsov was shot.

Then there’s the roll call of individuals who have run foul of the Kremlin, including journalists, political opponents, or defecting security agents. Poisoning was the preferred method but at least one, ‘opposition’ leader Boris Nemtsov, was fatally shot near the Kremlin in 2015.

Sweeney’s evidence of Kremlin involvement is that no location in Russia is more closely monitored or policed, yet no footage exists. Suspects may be arrested but these are easily found in a police state. No-one has been charged with Nemtsov’s death.

The modus operandi in all of these events is all too familiar, and well known from books by Masha Gessen, Catherin Belton, and Luke Harding, whose Shadow State, reviewed in January, is a litany of Kremlin perfidy that differs only in minor detail from Sweeney’s.

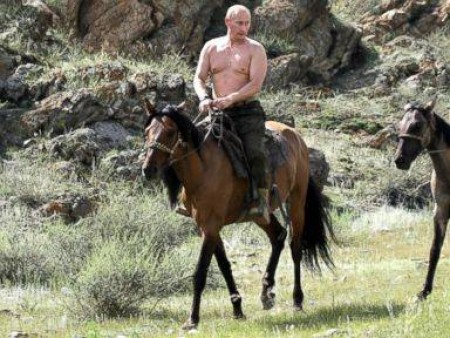

President Putin is said to use steroids after a horseback fall.

Occasionally, Sweeney breaks his narrative to explain the nature of Putin’s evilness and why he would invade Ukraine, even if it meant rallying the Western world against him after it earlier gave him the benefit of the doubt.

On one page, he “is a military incompetent … a weak authoritarian personality, because he is afraid of his own death … he is supremely paranoid.”

On another, Sweeney dismisses comparisons with an insane Hitler. “Putin is a rational actor inside a bunker, so deep, so deprived of light and information, that he is pulling levers without understanding how the modern world is responding…”

Elsewhere, Putin is a “pleonexiac” – obsessed with greed – and also with his health. He is described as a heavy user of steroids for a back pain caused by falling off a horse, employs Botox to hide the side effects of drugs, and is being treated for various forms of cancer. These make him hyper-aggressive.

Wondering how Putin could blatantly lie in the Sochi doorstepping over MH17, Sweeney seeks the opinion of a professor of psychiatry at the University of California. He is told: “Psychopaths are very good at lying … They don’t think what they are doing is immoral or wrong. [He’s] typical of all psychopaths and also people with narcissistic personality disorder,” and so on.

Others have looked into Putin’s childhood, rumours of abandonment and abuse, his early career as a KGB agent, and rise from relative obscurity for clues. But Sweeney confesses: “We don’t know the whole story, and probably never will.”

That sums up Sweeney’s book, whether you read it for its entertainment value or accept it as a mix of fact and fiction.

Killer in the Kremlin

Killer in the Kremlin: The explosive account of Putin’s reign of terror, by John Sweeney (Bantam Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.