The Covid conspiracies that fuel extremism

ANALYSIS: Guide to New Zealand’s alt-right shows surprising variety.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

ANALYSIS: Guide to New Zealand’s alt-right shows surprising variety.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

The most common family of conspiracies are known as the ‘Great Reset’, wrote Jack Shenker in 1843 magazine, published last month by The Economist. His article described how its followers believe that global elites are using the Covid-19 pandemic to “engineer a power grab, and that the pandemic is a monstrous charade designed to terrify ordinary people into a submission”.

The evidence is that in the northern summer of 2020, the World Economic Forum launched a ‘Great Reset’ to guide the world’s recovery from Covid and was drawing up a “new social contract” with the help of stakeholders and supporters such as Prince (now King) Charles, Al Gore, and some of the world’s biggest companies.

As the Great Reset theory spread, it fused with the pre-existing anti-vaccination movement, Shenker went on, pointing out that the common bogeyman of both beliefs was Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft, philanthropist, Covid-vaccine funder, and WEF partner.

Not so long ago, I was a keen follower of the WEF, an organisation founded in Switzerland in 1971 and which, along with a think tank called the Mont Pelerin Society formed in 1947, championed the cause of free markets and globalisation.

In short, it promoted neoliberalism as means by which big business and governments could promote the benefits of capitalism in a sustainable and ethical way. The WEF was therefore always part of a conspiracy: that of capitalists and free markets running rampant over the planet and exploiting all workers in the name of profit.

At the annual meetings at Davos in late January, celebrated business moguls such as Gates, Rupert Murdoch, and the grandees of Wall Street rubbed shoulders with prime ministers and presidents from the first and third worlds.

The second or Communist bloc was noticeably absent, but this changed with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It was a vindication that freedom and democracy, along with capitalism, underpinned the ideas behind the WEF.

World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab conceived the ‘Great Reset’.

The founder, business professor Klaus Schwab, was acclaimed for bringing together some of the main adversaries of the 1980s and 1990s: Greece and Turkey; South African President FW de Klerk and Nelson Mandela; Israel’s Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat.

China began attending the Davos summit in 2017 and politicians, rather than businesspeople, began to set the agenda. New Zealand took little notice of Davos until Jacinda Ardern started attending, perhaps prompted by her former boss, Tony Blair, who was on the WEF board in 2010.

At the peak of Davos fever, in 2018, more than 3000 participants attended from nearly 110 countries. This included 340 public figures, 70 heads of state, 45 heads of global organisations, and 230 accredited media groups.

Schwab’s declaration of the Great Reset was a denunciation of WEF principles. “[S]hibboleths of our global system will need to be re-evaluated with an open mind. Chief among these is the neoliberal ideology. Free-market fundamentalism has eroded worker rights and economic security, triggered a deregulatory race to the bottom and ruinous tax competition.”

He further defined this as “stakeholder capitalism”, in which companies do not only optimise short-term profits for shareholders but seek long-term value creation. In simple terms, Schwab was promoting corporatism rather than free markets, and it was music to the ears of left-wing social democratic governments, who previously viewed Davos as a big business plot run for the benefit of Wall Street.

It’s easy to see how New Zealand’s Labour government in 2020 could go along with the WEF agenda, supported by academics and others committed to a stakeholder-capitalist Aotearoa. The Council of Trade Unions and researchers at Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga both produced lengthy papers supporting corporatism if not outright socialism. In Australia, Treasurer Jim Chalmers produced a 6000-word manifesto for an activist state running a corporatist economy.

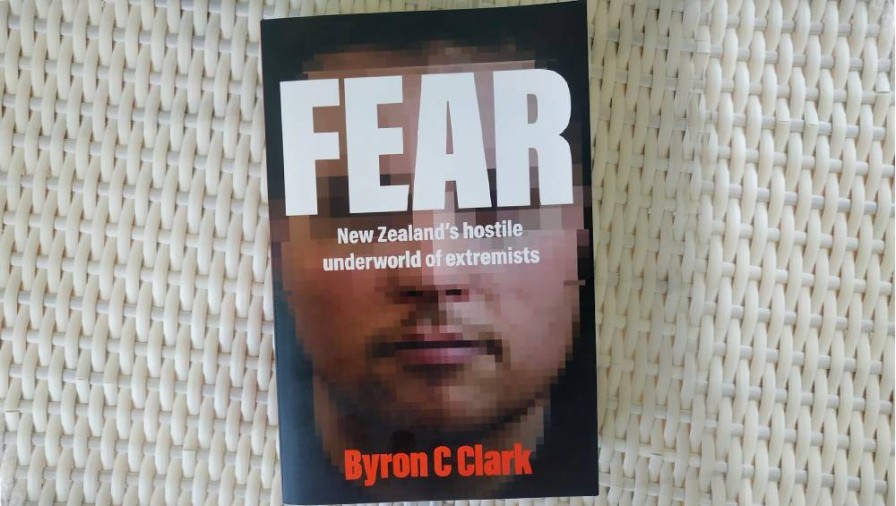

But how did the WEF become the root of the alt-right conspiracies in Shenker’s article? The answer is partly presented in Fear, Byron C Clark’s new study of New Zealand’s “hostile world of extremists” This is a broad sweep through a fragmented movement that has been demonised by mainstream media since the Covid-19 outbreak.

Byron C Clark.

Clark is a Christchurch-based socialist who was spurred by the March 2019 mosque massacres to spend his time combing Facebook for right-wing ranters and shopping them for illegal hate speech. His research also included ‘field trips’ to meetings held by the scattered groups on the extreme right.

While most are political, some have a religious bent. The Catholics have the Society of St Pius X, which prefers the traditional Latin mass. One of Clark’s omnipresent alt-righters attended Pius X services in the hope of influencing a priest in anti-Zionism and Holocaust denial.

Other groups with a religious focus are defenders of Israel, such as the Pentecostal churches that include City Impact, which has attracted media attention due to its labour practices as well as its anti-vaccination stand.

According to Clark, Vision NZ, Christian ONE, and New Conservatives support closer relations with Israel. They also share a popular belief that the Labour government has an anti-Christian agenda and condones immigration from Muslim-dominated countries. Opposition to the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration of 2018 was a touchstone for a while, as were campaigns against 1080 poison and 5G cellphone towers.

But, as you would expect, a more traditional strain on the far right is anti-Semitic. “While clashing egos and petty sectarianism appeared to be the main divide between populist right-wing parties, the significance of race and racism can’t be understated,” Clark writes.

The far right has appeal to some Māori due to their generational distrust in government. Billy Te Kahika’s NZ Public Party achieved traction but attempts to form a united front for election purposes failed, though its association with former National MP Jami-Lee Ross’s Advance NZ attracted some 28,000 votes in the 2020 election.

Clark identifies a Samoan talkshow, Talanoa Sa’o, produced by Apna Media Network, as being akin to a Fox News of the Pacific with its message that not all “white people are bad and brown people are oppressed”.

Elliot Ikilei was a New Conservatives candidate in the 2020 election.

Clark quotes Efesa Collins, a Green Party member and unsuccessful Auckland mayoral candidate in 2022, who dismissed this thinking in the Pasifika community as simplistic and assimilationist. The broadcasts featured Elliot Ikilei, who was fond of quoting American economist Thomas Sowell, and were eventually shut down.

It was coincidental, Clark writes, that he had lodged a complaint with the Broadcasting Standards Authority on the racial content of Apna’s programmes.

Also on Clark’s list of alt-right and extremist issues are use of rural land; expats who have a museum dedicated to Ian Smith’s Rhodesia; Hindu nationalists opposed to Muslims; traditional roles for women; speculative fiction about dystopian futures; the government-funded disinformation project; and the anti-vaxxers who brought many of these groups together in the protests at Parliament in February 2022.

While some also had mainstream concerns, such as the farmers’ Groundswell movement and orthodox religious beliefs, Clark asserts alt-rightists hijack these causes for their own ends, boosted by their access to alternative media such as Counterspin. Extremists are also seeking public office, which was the subject of media attention during the local government elections last year.

One of the most interesting revelations is Clark’s outline of the disinformation project, which started with public health advice to counter anti-vaccination campaigners. It has since expanded to monitor opponents of gun control; rural land rights activists; Māori sovereignty, including Three Waters; and Christian/Islamic views on abortion and gender issues.

In a report, the project’s researchers noted a “near-frictionless shifting of New Zealanders from vaccine hesitancy to vaccine resistance, and then to content reflective of wider conspiratorial ideologies” associated with the QAnon platform. “These include white supremacist, Incel or extreme misogyny, Islamophobia and anti-migrant sentiment, and anti-Semitism. We have also observed increasing levels of anti-Māori racism.”

The project report sums up its observations: “These efforts result in, online, emotional contagions through reflexive sharing and reactions, and through instrumentalisation of anger, antagonism and anxiety, give rise to, offline, the formation and cementing of attitudes, perceptions and behaviours without critical reflection.”

The project’s worst fears were realised in the Parliament protest. Clark concludes: “The protesters may have left for now. However, the disinformation networks that led to this moment remain.”

Fear: New Zealand’s hostile underworld of extremists, by Byron C Clark (HarperCollins). Release date: February 15.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.