Costs and benefits of living wage campaign

ANALYSIS: Impact is not as effective or as damaging as supporters and critics would claim.

Power to Win: The Living Wage Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand, by Lyndy McIntyre.

ANALYSIS: Impact is not as effective or as damaging as supporters and critics would claim.

Power to Win: The Living Wage Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand, by Lyndy McIntyre.

In left-wing circles, Saul Alinsky is revered as much as Michael Joseph Savage and Barack Obama. Known as the father of community organising, Alinsky recognised that while there was no lack of solutions for poorer communities, they lacked the power to implement them.

Alinksy began his work in Chicago during the 1930s and put a lifetime’s work into a book, Rules for Radicals, published in 1971, a year before his death. He realised communities could only build long-term power by organising around a common vision. This meant identifying groups with a common purpose and getting them to work together.

This was more effective than each group, such as trade unions, churches or charities, doing their own thing. Alinsky also taught forging these groups into an effective force was more important than winning on a single issue.

Lyndy McIntyre.

These ideas were fined tuned into courses that could train organisers and be implemented anywhere in the world. Typically, Alinsky’s methods were picked up by trade unions that had a broader vision than just pushing the cause of higher wages and conditions. It meant using less-disruptive techniques than strikes or industrial action.

An important factor was to gain support from members of the public rather than alienate them, as most industrial action did in the 1970s.

A new book, Power to Win, by Lyndy McIntyre, is a case study of an issue – a living wage – and how it was achieved over the past 12 years. McIntyre was on the inside of this campaign from the beginning and provides a detailed account of its history.

The idea of a living wage – one that gives an adequate income for a family of four to live in dignity – is not new but ways to achieve it are limited by the unions’ lack of a wider community base.

The Service and Food Workers Union (now E Tū) appointed Annie Newman as convenor of the campaign, which drew from Alinsky’s principles as well as the practical experience of groups such as London Citizens.

One difference from Alinsky was that an issue had been chosen before the broader community was organised. Newman initially targeted groups committed to addressing poverty and inequality.

Annie Newman at a rally on the steps of Parliament in November 2017.

Buy-in from the media was important and immediate; poverty was solidly on the news agenda. The concept of families with working members being able to afford the necessities of life is easy to grasp. So was the inclusion in a living wage of a home computer, occasional eating out, school trips, and participation in community responsibilities.

More than 50 groups, including major religious denominations, charitable trusts, and unions with low-paid members, signed up before the launch of the Living Wage Movement (LWM) in 2012.

While unions focused on higher pay, other stakeholders were more interested in social justice and poverty reduction; causes that “are often built on a desire to collectivise individuals – such as migrants and refugees or people concerned with environmental issues – and unite them around particular issues identities,” as McIntyre puts it. In other words, classic identity politics.

The next step was identifying a group of low-paid workers. This was also an obvious one: cleaners at AUT, a university known for its left-leaning academic staff and publicly funded.

The LWM viewed the public sector as a ‘soft’ target and more likely to respond to its methods: presenting actual examples of cleaners, security workers, care workers, and hospital orderlies in forums such as council meetings and media stories.

Readers may recall how homelessness, poverty, and mental illness were major issues in the 2017 election won (with help from NZ First) by Labour’s Dame Jacinda Ardern. These were absent in the 2020 Covid-19 election, which gave Labour an absolute majority.

TV3’s John Campbell interviewed people living in cars, the New Zealand Herald’s Simon Collins and researcher Max Rashbrooke presented analytical articles on poverty, backed up by university-based and other groups.

Labour mayors and councillors in metropolitan cities were easily persuaded of the public appeal for a living wage, though council officials often mounted a resistance to the extra burden on ratepayers.

McIntyre bluntly states that, in the case of the Wellington City Council: “The campaign to lift the wages of … lowest-paid workers could never have been won through direct bargaining across the table with contractors. Instead, the local [LWM] network built the necessary power to convince Wellington local body politicians to take action.”

Councils are legally bound to apply competitive tendering for contracted services such as cleaning and security, jobs that often paid mandatory minimum wage rates. Newman was ideologically opposed to moves that cut costs: “It is a false economy because ultimately everyone suffers from the poverty wages paid to these workers.”

Charles Waldegrave unveils the first living wage rate in February 2013.

Charles Waldegrave, a policy researcher, created a living wage formula for a family of four that few would quibble about. The only opposition came from business think tanks and tax watchdogs that worried about the inflationary impact on costs.

But the LWM pointed to the voluntary nature of a living wage. It was up to employers to work out whether they could afford it. Employers who signed up to LWM accreditation also had to meet other conditions. These were modest but The Warehouse decided to go on its own, earning a label of ‘free-rider' by refusing to pay fees to the LWM.

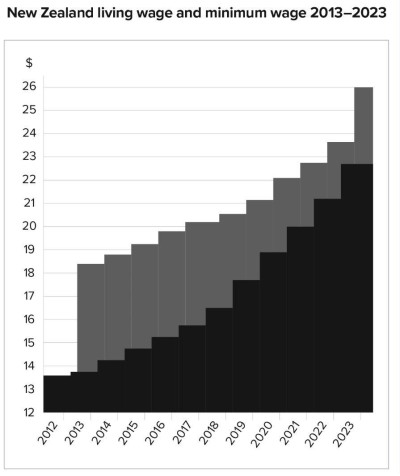

Source: Eleanor McIntyre.

The initial living wage was set at $18.40 an hour ($736 a week) in 2013 compared with a minimum hourly wage of $13.85. The gap of $4.45 has narrowed ever since, thanks to the minimum wage increasing at nearly twice the rate of inflation between 2016 and 2023.

In 2022, the gap was just $1, before the living wage rose to $26 an hour compared with the latest minimum wage of $23.15, a lower-than-inflation increase. The proposed rate from September is $27.80, widening the gap to $3.65 (the two rates are set six months apart).

The minimum wage is roughly 72% of the median wage, relatively high compared with other OECD countries. Research shows most are young people, many living at home, and part-time employees.

In 2021, Motu Research concluded: “Our analysis implies that minimum wages are largely ineffective as a redistribution tool, given the broad incidence of minimum wage workers across the household income distribution – many people on low hourly rates of pay are nevertheless in households where incomes are not particularly low.”

The Motu paper also found no clear evidence that increases in the minimum wage had led to negative employment losses for affected groups. The research showed the minimum wage policies were neither as effective, nor as damaging, as its supporters and critics would claim.

The same can probably be said for the living wage. Whenever it is debated in the media, the LWM can put up supportive employers and employees, while opposition is left to lobbyists rather than actual employers for fear of reaction. (McIntyre cites the example of an NBR journalist asking her for an employer who would speak up against a living wage.)

It can justifiably be said the LWM has fulfilled its aim and is likely to fade in its second decade. Much will depend on the political and economic environment, which is less favourable to the small business sector absorbing higher wage costs.

McIntyre has retired from union work, and Newman is no longer national convenor of LWM but remains assistant national secretary of E tū. Their successors will find it harder if they tackle what’s left of sectors that depend on the labour of migrants from low-wage countries.

Power to Win: The Living Wage Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand, by Lyndy McIntyre (Otago University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.