The case against military-based defence force

Three Otago academics suggest different priorities to meet security threats.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Three Otago academics suggest different priorities to meet security threats.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

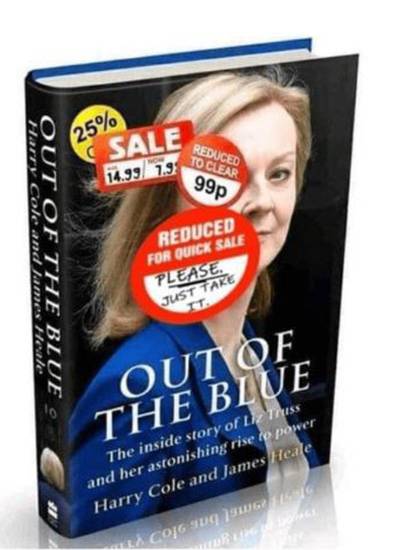

Two British political journalists made one of publishing’s greatest mis-timings when their biography of Liz Truss was rush-written over 10 weeks and set for publication on December 8, 2022.

It was called Out of the Blue and publicised as: “The inside story of Liz Truss and her astonishing rise to power.” Truss was elected successor to Boris Johnson as leader of the Conservative Party on September 6. She was sworn in by Queen Elizabeth II, who died two days later.

But Truss’s term as prime minister was cut short due to a mini-budget that combined a neoliberal tax cut and a spending programme worthy of the Labour opposition. Financial markets had a fit, forcing her resignation on October 25, after just 45 days.

Four days later, on the book’s copy deadline of October 29, one of the biographers, James Heale, wrote in The Spectator that a heavily Photoshopped promotional cover had become an internet sensation. It had stickers reducing the price to 99p and finally, “PLEASE. Just take it.”

The heavily Photoshopped promotional cover had become an internet sensation.

The publication date was moved forward to November 1 for an electronic version and to November 24 for the print edition with the subtitle amended to Truss’s “unexpected rise and rapid fall”.

Its fate is a footnote in publishing history. The 102nd title in the provocative BWB Texts series is unlikely to achieve the same notoriety. But the three University of Otago academics who wrote Abolishing the Military: Arguments and alternatives could have hoped for better timing to launch their case for dismantling the New Zealand Defence Force.

Dr Griffin Manawaroa Leonard, Dr Joseph Llewellyn, and Professor Richard Jackson are all affiliated to the university’s National Centre for Peace and Conflict. They finished the text before the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, which has dominated world news ever since and pushed the Russian invasion of Ukraine into the background.

Some might welcome a discussion on whether defence forces deliver value for money, effectively contribute to national security and international peacekeeping, or that some roles that could be done better by other specialist agencies. But it’s unlikely such a time is when the world is in a heightened period of turmoil.

The authors admit as much, saying the Ukrainian response to the Russian invasion is as close to a “just war” as you are likely to get. Most of the material in this brief book is drawn from the same events depicted in Conflict, the study of wars since 1945 by former US General David Petraeus and British military historian Lord Andrew Roberts, reviewed here a few weeks ago.

These two books are surprisingly complementary, given both reveal the hugely destructive nature of wars and the lack of peaceful outcomes that often follow them. Both the advocates of military preparedness and those who seek alternative courses can claim wins and losses.

While Conflict is strong on historical perspective, and therefore takes a dim view of humanity’s ability to solve disputes without resort to force, the pacifist approach is optimistic to the point of utopian. But as the Otago academics point out, things once considered impossible can decades later be acceptable.

What is known is that non-violent methods aren’t a recent phenomenon. Māori used passive resistance against colonialism long before Gandhi in India. Protests were held against the involvement of New Zealand troops in South Africa (1899), the conscription laws of 1909, and the Vietnam war in the 1960s.

L-R: Professor Richard Jackson, Dr Joseph Llewellyn, and Dr Griffin Manawaroa Leonard are all affiliated to the university’s National Centre for Peace and Conflict.

The authors argue their case through four ‘myths,’ defined as a “mix of facts, history, assumptions and beliefs [that] contribute to rigid ways of thinking about a problem and inhibit reflection and continued critical assessment”.

The myths are:

These are all subjected to critical scrutiny. In the first example, the NZDF carries out functions such as emergency assistance, fisheries protection, disaster relief, peacekeeping, cyber attacks and, during the pandemic, manage quarantine facilities.

The authors suggest none of these need a combat-ready force and would be better run by specialist agencies. New Zealand cannot provide a large armed force to repel invaders; instead our military forces are designed to work under the umbrella of larger countries with objectives that may be incompatible to our values.

Of course, it can be argued New Zealand is better off under this system, even if it means accusations of ‘not pulling its weight’ and being subject to outside pressures, such as participating in the 'global war on terrorism’.

It’s true civilian causalities from the anti-terrorist actions taken after 9-11 (2001) in Afghanistan and Iraq far exceeded the number of victims of terrorism, and this is continuing in places such as Syria, Somalia and Yemen. But this balance sheet approach ignores the wider considerations that taking no action could have been worse.

The authors identify plenty of military interventions, including UN peacekeeping, that have failed miserably. They say this “unsettling record” is “chequered at best and shameful at worst” in places such as Rwanda, Congo and Bosnia, as well as the countries already mentioned.

On the positive side, many examples of alternative methods, such as unarmed civil peacekeeping (UCP), have been successful in resolving conflicts. Examples include Guatemala, El Salvador, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Indonesia, and Georgia. The NZDF role in Bougainville and Timor-Leste is acknowledged as positive, though the Solomon Islands has been less successful.

The RNZAF supplied two helicopters for security during the Pacific Games in the Solomon Islands. Credit: NZDF.

In exposing the fourth myth, of civilian-based approaches, the authors examine Costa Rica’s demilitarisation of its security needs. They quote studies by American political scientist Gene Sharp, who found non-violent changes of government were twice as likely to have favourable outcomes than the use of force.

It is asserted, “military intervention has a poor record in building free, secure and democratic post-conflict, post-authoritarian societies [but] a consistent record of causing a great any civilian casualties and societal destruction”. The prime examples of civilian-based peaceful changes are Portugal in 1974, and the dismantling of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe after 1989.

The authors note the failure of military interventions to achieve peaceful outcomes is reflected the low spending priority of overseas involvement by the NZDF – in 2011, the contribution to the UN was $22.2 million compared with the total defence budget of $2.8 billion.

This slim volume is a valuable contribution to public debate, though it plays down the economic justification for a defence force as insurance for the protection of trade routes. In debating terms, the authors score easy points on weaknesses in the NZDF’s multiplicity of functions, expensive procurement policies (one frigate equals a public hospital), and the lack of innovative civilian-based forms of resistance such as that employed in Lithuania.

Their arguments could be better expressed by dropping the clunky language prevalent in academia that has no place in public discussion. One is the heavy use of redundant synonyms, such as “unquestioned and unexamined acceptance”, “honest and scrupulous”, “effective and more appropriate”.

Another is fashionable overuse of “Aotearoa New Zealand” with “New Zealand” being dropped after a few mentions and then repeatedly reintroduced. Let the case for a deterrent defence force be similarly presented, preferably in a more concise language.

Abolishing the Military: Arguments and alternatives, by Griffin Manawaroa Leonard, Joseph Llewellyn, and Richard Jackson (BWB Texts).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.