The battle against disinformation, and how to win it

OPINION: Twitter takeover symbolises struggle to retain control over truth.

OPINION: Twitter takeover symbolises struggle to retain control over truth.

Free speech has become the frontline over the clash of values in the cultural wars.

‘Cancel’ groups wanting to curb extremist views on religion, gender, and race are pressuring Western governments to suppress them.

The world’s richest man, Elon Musk, thinks otherwise and is prepared to pay US$44 billion to transform Twitter into a bastion of free speech.

He believes Big Tech – Meta/Facebook, Alphabet/Google/You Tube, TikTok, etc – are censoring their platforms to eliminate opinions that don’t fit with their Silicon Valley version of Democratic liberalism.

In political terms, that means curbing Republican conservatism, including that of Donald Trump, who is banned on both Twitter and Facebook.

“This is not about the economics,” says Musk, whose own views sound libertarian. “My strong intuitive sense is having a public platform that is maximally trusted and broadly inclusive is important to the future of civilisation.”

Musk has backup if not approval from Francis Fukuyama, an intellectual famous for declaring “the end of history” – shorthand for the collapse of the Soviet Union as the ultimate “end point of mankind’s evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”.

That was written in 1992. Fukuyama has updated his thinking in Liberalism and its Discontents, which will be the subject of a future column.

Suffice to say, Fukuyama agrees with Musk that Big Tech has “neither the capacity, judgment, nor legitimacy to be the arbiters of what is appropriate political speech in any modern democracy”.

Which brings us to the freedom debate as cancel activists list hate speech, conspiracy theories, and so-called ‘fake news’ as reasons for legal constraints.

“All that kind of speech is protected by the first amendment,” Fukuyama told a competition policy conference in Chicago last weekend. “[In contrast], the power to mediate content is like a loaded gun that’s sitting on the table and trusting the guy at the other end of the table not to pick the gun up and to shoot you.”

On the other side of the debate, Barack Obama called for law changes that no longer shielded Big Tech from legal responsibility for the content third-party users publish.

“These decisions affect all of us and, just like every other industry that has a big impact in our society, that means these big platforms need to be subject to some level of public oversight and regulation,” Obama said.

Kinder version

In New Zealand, political discourse includes claims of misinformation, the kinder version of disinformation, of which more later. Opposition leader Christopher Luxon was accused of it in an interview on racial priorities for health provision. Act leader David Seymour used it against Māori Development Minister Willie Jackson in a discussion on race-based co-governance.

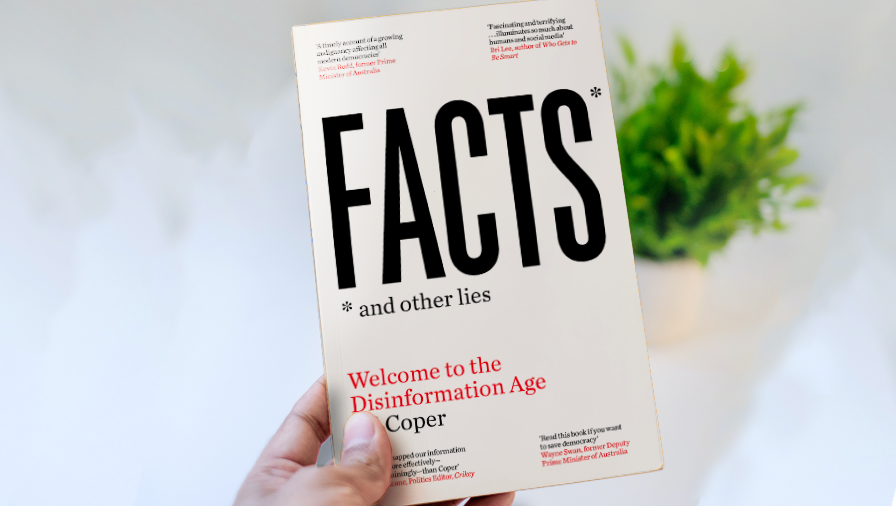

Misinformation is defined by Australian communications expert Ed Coper as the unintentional spread of incorrect information. By contrast, disinformation is the deliberate act of creating lies with the aim of deception.

Both are the outcome of major upheavals in the Information Age. In his book Facts and Other Lies, Coper describes how the rise of computers and the internet heralded an optimistic era that “unfettered access to information” of an informed citizenry “would break down cultural and political barriers, free people from the yoke of suppression, and spread knowledge previously hoarded in the dusty shelves of ivy-covered institutions.”

Like Fukuyama’s prediction, it was not to be. Instead, the opposite happened. “People retreated into likeminded bubbles of groupthink, autocrats entrenched their rule through social media, and knowledge was supplanted by ‘alternative facts’ that marched back and forth across the internet while the truth was still putting its pants on.”

Ginger group

Coper’s flamboyant prose reflects his background as a left-wing activist and founder of GetUp, a radical ginger group that uses social media to be a force in Australian politics. He also runs a think tank, Centre for Impact Communications, and is behind Change.org’s international expansion.

‘Our opinions are not guided by the facts; the facts are guided by our opinions.’

Coper is an accomplished researcher as well as stirrer. His 400-page study of disinformation, its history, causes and effects, is impressive, spoiled only by his obsession with Rupert Murdoch’s global media empire, Donald Trump, and Margaret Thatcher.

The Western media, including those owned by Murdoch, operate in the open, which is not the case for other – much more egregious – examples Coper cites, such as mass killings in India, Myanmar, and elsewhere spurred by WhatsApp or Facebook.

Coper provides a history of how humans have used lying as a psychological tool, starting with the Ancient Greeks, moving on to the Enlightenment, and the 20th century with its authoritarian ideologies.

“The collision between cognitive psychology and disinformation has upset the apple carts of political science and philosophy: we have been forced to learn that our opinions are not guided by the facts; the facts are guided by our opinions.”

Emotive opinion

Furthermore, disinformation has rewarded emotive opinion, suspicion, and division and has punished rational facts, nuance, and balance. Many would agree and be aware these “suspicions and divisions have been exploited with ruthless efficiency and brutal efficacy”.

This column has previously covered books on disinformation as an espionage tool against the West, notably by the Soviet Union and its successor the Russian Federation (Shadow State, Information Wars, Active Measures).

Coper is more concerned about the impact on ordinary citizens, who are more likely to be unwitting victims of nefarious disinformation and are faced with milder forms of it daily from vote-seeking politicians.

He pokes borax at Fukuyama, whose ‘end of history’ thesis was confounded by China becoming more rather than less autocratic as it overcame poverty; Trump seeing economic gains in protectionism rather than free trade; and regimes in Asia, Africa, and South America taking the path of tyranny rather than democracy.

It is little consolation that some of the latter – such as Venezuela, Libya, and Iran – are much worse off despite their resource advantages.

“While we might not have seen the end of history, we have now seen the end of a golden age of truth and reason,” Coper observes.

He outlines the role of algorithms, formerly an obscure term only used in the teaching of mathematics. It is now the mechanism that “will always reward sensationalism, tribalism and innuendo over science, truth and interrogation”.

Golden age

But no amount of tweaking it “will reinvent the golden age of journalism, or restore trust in our honest politicians, or elevate reason to a place in our brains that trumps emotion,” Coper contends.

It is too late because those platforms are a product of our times. Apart from ways individuals can detect and combat disinformation, most of which are commonsense, Coper also outlines suggestions for greater transparency in how information on consumers once held by the mass media is now controlled by the Big Techs of social media.

This takes us back to the regulatory path advocated by Obama, or Jacinda Ardern’s Christchurch Call, among others. Incidentally, Coper praises Ardern for her pledge, before the 2020 election campaign, warning electors to be aware of disinformation before any examples had occurred. This tactic is known as inoculation. But no mention is made of her international efforts to tame Big Tech.

Coper is unconvinced governments can provide the solution, as they are still trying, or unable, to understand how the internet works. This is illustrated by their attempts at censorship, either through regulation or depending on the platforms themselves.

He partly blames the collapse of the former media landscape on government ignorance, and encourages efforts to restore local news, investigative journalism, and public broadcasting through alternative funding.

This has proved contentious in New Zealand, particularly through the perception that it comes with Treaty of Waitangi strings attached, something Coper isn’t likely to experience in Australia.

Facts and Other Lies: Welcome to the Disinformation Age, by Ed Coper (Allen & Unwin).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.