Take a roller-coaster ride with Slavoj Žižek

ANALYSIS: Radical philosopher sees contradictions in everything, everywhere, all at once

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Radical philosopher sees contradictions in everything, everywhere, all at once

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

A fractious world riven by countless crises suggests a fertile place for philosophical discussion. But any attempt to tap academia for enlightenment soon runs into arcane territory.

On the outskirts, some are prepared to enter a public debate on the big issues. One area that has logged a vast number of pages as well as You Tube items is the differing merits of capitalism (or neoliberalism) and socialism (or neoMarxism).

Leaving aside the economic issues, the debate has been muddied with psychoanalysis.

On the Left, the main practitioner is Slovakian-born Slavoj Žižek, who attracts the same sort of attention as Jordan Peterson on the Right for their polymath qualities and ability to speak at length on just about any topic. (Their 2019 debate in Toronto on happiness runs to two and a half hours on You Tube and is available in two versions, with a total of more than nine million views.)

Slavoj Žižek and Jordan Peterson at their 2019 debate.

Peterson requires no introduction to readers of this column but Žižek is making his first appearance. The hook is his latest book, Surplus-Enjoyment: A guide for the non-perplexed, which he says is about a topsy-turvy world “where multiple catastrophes – pandemic, global warming, social tensions, the prospect of full digital control over our thinking ... compete for primacy”.

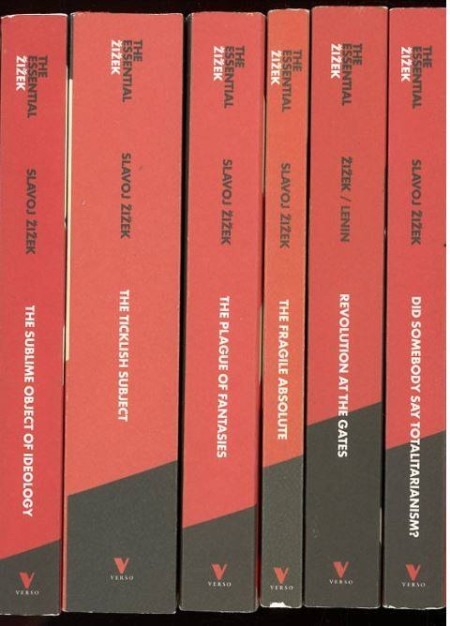

Compared with Peterson’s modest literary output, Žižek is the Henry Ford of academia, churning out some 50 books in English in just 23 years. He has also been published in multiple other languages.

Occupationally, Žižek holds several academic posts: international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New York University, and a senior researcher at the University of Ljubljana’s Department of Philosophy.

He acquired celebrity status because of his idiosyncratic style as a public speaker, op-ed contributor, and critic of movies, classical music, and theology. His academic works are praised as an interpreter of German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831) and French psychoanalyst Jacques Lancan (1901-81).

English conservative Sir Roger Scruton delivered a backhander in saying his greatest regret in the collapse of Eastern European communism was “the release of Žižek on the world of Western scholarship”. Typically, Žižek quotes this to denigrate Scruton as being oblivious to the horrors of communist totalitarianism.

Sir Roger Scruton.

Scruton accused Žižek of slipping between philosophical and psychoanalytical ways of arguing. “He is a lover of paradox, and believes strongly in what Hegel called ‘the labour of the negative’ though taking the idea, as always, one stage further towards the brick wall of paradox.”

At worst, Žižek is accused of obfuscation, which is surely the case of anyone writing an academic argument, and inconsistency. This is also true of provocateurs but does not make them any less interesting.

Scruton’s objections are like those of another British philosopher, John Gray, who questioned Žižek’s professed belief in communism as lacking any conviction that it could ever be successfully realised. Gray’s summary was that Žižek's work was entertaining but intellectually worthless.

Žižek’s started as a student of the postmodern French structuralists and built his early reputation with translations into his native Slovenian of works by Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Sigmund Freud, and Jacques Lacan. These forged the notion of using psychoanalysis to interpret Hegel and Karl Marx, who drew heavily from Hegel in the development of dialectical materialism.

Žižek also delved into popular culture, writing introductions to works by GK Chesterton and John Le Carré. Among Žižek’s prodigious output of documentaries are The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006) and a companion one on ideology (2012). His favourite authors are Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, and Andrei Platonov, a Soviet writer who died in 1951 and whose main works weren’t published in his lifetime.

But none of this prepares you for the books, which combine philosophic argument with everyday beliefs, observations, and practices. His ‘topsy turvy’ world is bedevilled by countless crises, flavoured by his use of Hegelian dialectics in what might alternatively be described as ‘unintended consequences’.

But none of this prepares you for the books, which combine philosophic argument with everyday beliefs, observations, and practices. His ‘topsy turvy’ world is bedevilled by countless crises, flavoured by his use of Hegelian dialectics in what might alternatively be described as ‘unintended consequences’.

Consider his analysis of the retreat from Afghanistan by American-led forces: the Left cheered the withdrawal and the Taliban’s triumph. But this praise was immediately followed by concern for the plight of Afghan women who lost what few rights they had.

The Leftists found themselves on the side of Muslims, who attacked the best of Western civilisation: its egalitarianism and personal freedom. The Taliban, of course, were a reaction to the modernisation imposed by the Soviet-backed government that was in power during the 1980s.

Such examples occur throughout the dense text of Surplus-Enjoyment that provides a roller coaster through the Covid-19 pandemic, governments’ use of lockdowns and vaccine mandates to prevent virus contagion, and the inevitable dialectic reaction of the anti-vaxxer rebellions.

This protest was merged with other struggles against state control, corporate economic exploitation, and science. For the record, Žižek approves the use of vaccines, and contrasts their rejection today with the acceptance of mandatory vaccines in previous decades that eliminated other pandemic diseases such as polio and measles.

Paradoxes are everywhere in a dialectic world. It is okay to change gender in many societies but not race; the techno-scientific civilisation is blamed for global warming but is also essential in defining its threat.

Joaquin Phoenix in Joker.

Music (and some poetry) celebrates rape and murder as the privilege of victimhood and misery – “the brutality of rap lyrics is absolved in advance as the authentic expression of black suffering and frustration”. One of the pleasures in Surplus-Enjoyment are lengthy analyses of the Joaquim Phoenix movie Joker (2019), the Icelandic TV series Katla, the Russian version of Solaris, and a comparison of Shostakovich’s symphonies.

Žižek’s disdain for PC socialism as inevitably leading to tyranny is balanced by his equally trenchant criticism of utopian socialism. This is outlined in Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism (2000), which describes a “collective future of freedom and luxury for all” with the production of goods and services done by automation, robotics, and machine learning.

The catch-22 is that capitalism, which creates these riches, does not share them. But achieving this, according to Žižek, would be at the cost of “unheard-of possibilities of control and regulation of our lives”.

This resembles his comparison of solutions to global warming with Lenin’s “war communism” that imposed economic controls in the early days of the Soviet Union. The necessary measures would include a guarantee of minimal survival conditions through mobilisation of resources, displacement of populations, and limits on political democracy.

“A much stronger executive power capable of enforcing long-term commitments will have to be combined with local self-organisations of people, as well as with a strong international body capable of over-riding the will of dissenting nation states,” Žižek states.

Immanuel Kant.

The Chinese model of communism doesn’t appeal as it has no public feedback or open debate on measures. As with the early history of vaccines, once approved by those affected, obedience is obligatory.

He reworks Immanuel Kant’s formula of enlightenment as: “Think, freely, state your thoughts publicly, and obey [emphasis in the original].”

Žižek attacks the imposition of “fake egalitarianism,” saying it’s “destined to just breed envy and hatred”. This is because a society based on notions that people will spontaneously work for the common good makes no room for Freud and the baser instincts of human behaviour.

These are a few of the many insights that justify Žižek’s contribution to modern issues. Take conspiracy theories, which usually start with a claim to want a debate and to look at all sides rather than accept an official view.

But this is replaced with a scepticism that turns into its opposite, a “unified total explanation”. Žižek describes this as “surplus enjoyment” – a phrase Lacan took from Marx’s surplus capital to describe capitalist exploitation.

It would take many more words to try to explain, let alone understand, this addiction to pleasure in a state of oppression. The value in reading Žižek is to recognise that all the accepted faults in society can be viewed as contradictory.

He even provides a dialectical compromise between the Right – which respects its own culture and despises others – and the Left – which despises its own culture and respects others. Together they “bring out hidden antagonisms of their own cultures, link it to ones in other cultures, and engage in a common struggle”.

This echoes Catholic writer GK Chesterton’s dilemma of the surrounded soldier in Orthodoxy (1908), which Žižek chooses for his coda: “He must seek his life in a spirit of furious indifference to it; he must desire life like water and yet drink death like wine.”

Commentators have variously described Žižek as a gadfly who infuriates people, a believer in a philosophic Ponzi scheme, and promoter of nonsensical theories that are deeply pessimistic. Žižek’s star may have waned since the halcyon days of Occupy Wall Street but he remains, at 74, a keen observer in picking out absurdities in a world of cultural offences.

Surplus-Enjoyment: A guide for the non-perplexed, by Slavoj Žižek (Bloomsbury)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.